Archive

One Continuous Picnic: A gastronomic history of Australia by Michael Symons

by Leo Schofield •

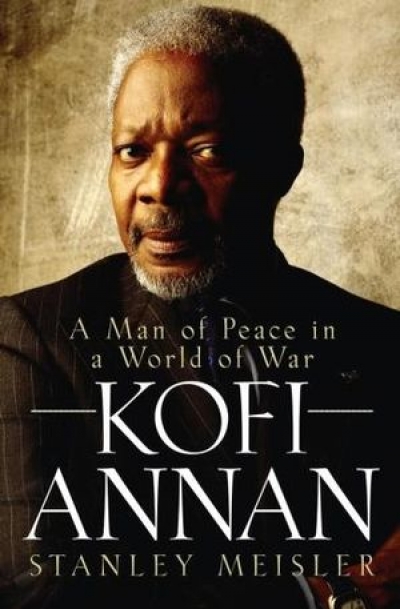

Kofi Annan: A man of peace in a world of war by Stanley Meisler

by Alison Broinowski •

Writing The Story Of Your Life: The ultimate guide by Carmel Bird

by Shirley Walker •

Strangers in the South Seas: The idea of the Pacific in western thought edited by Richard Lansdown

by Kate Darian-Smith •

The Escape Sonnets by Brian Edwards & Couchgrass by Dominique Hecq

by Anthony Lynch •

Mind the Country: Tim Winton's fiction by Salhia Ben-Messahel

by Georgina Arnott •