Hergesheimer Hangs In

Arcadia (Press On Series 9), $24.95 pb, 220 pp, 9781921875342

Hergesheimer Hangs In by Morris Lurie

‘A writer is writing even when he’s not writing, maybe even more then, even if he never writes again.

Got it?

Class dismissed.’

(Morris Lurie, ‘On Not Writing’, in Hergesheimer Hangs In)

In Wild & Woolley: A Publishing Memoir (2011), Michael Wilding recalls: ‘Morris Lurie sent us a collection, too. I think if he had sent it eighteen months later I would have published it. But when he sent it, right at the beginning, I was narrowly committed to a particular experimental, innovative, new writing … Not publishing Lurie was a decision I later regretted. Over the years I continued to read him, and was increasingly taken by the wit and economy and human observation of his writing.’

Hergesheimer Hangs In bears the prefatory line ‘Commissioned by Michael Wilding’, showing him to be true to his reconsiderations. I nervously checked the details of Contemporary Classics, an anthology of ‘The Best Australian Short Fiction 1965–1995’, which I edited in 1996. To my relief, it includes a story by Lurie: ‘Camille Pissarro 1830–1903’, from The Night We Ate the Sparrow (1985). The story’s title inevitably reminds one of Donald Barthelme, the pre-eminent American short fiction writer of the 1960s and 1970s, especially in the pages of the New Yorker. We should perhaps recall the bitter words of a character in a Frank Moorhouse story: ‘Meanjin. That’s Aboriginal for “Rejected by the New Yorker.”’

Lurie, born in Melbourne in 1938, who has published in both the New Yorker and Meanjin, is the author of at least twenty-five books. His 1978 novel Flying Home was named by the National Book Council as one of the ten best Australian books of the decade. In 2006 he received the Patrick White Award for under-recognised, lifetime achievement in literature. To persevere with the American connection, there was, as Lurie points out in the twenty-fourth (of twenty-six) ‘chapter’ of this book, an actual American Hergesheimer (Joseph), ‘an American writer of great popularity who fell from favour, couldn’t understand it, didn’t know why, bellyached about it endlessly to his pal Mencken, refused to go gently, if you like, into that good night, is quite forgotten now. I appropriated his name to pass unnoticed, as it were, among you.’ Only to point it out, to underscore it so to speak, thus defeating its initial purpose.

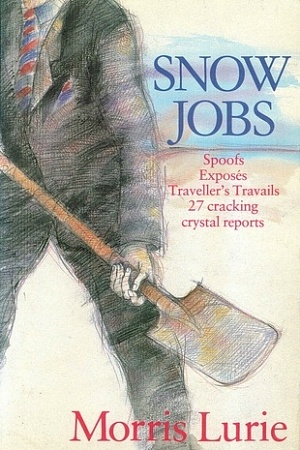

The historical Hergesheimer was born in Philadelphia (W.C. Fields: ‘I went to Philadelphia once. It was closed’) and initially studied as a painter, but turned to writing. Hergesheimer Hangs In is illustrated by Lurie with cuts and crayons. Hergesheimer’s reputation fluctuated wildly in his own lifetime, from a peak of acclaim and popularity in the 1920s to almost total obscurity by the time of his death in 1954. Yet Samuel Beckett, when asked in 1962 what was his favourite American novel, replied: ‘one of the best I ever read was Hergesheimer’s Java Head.’ Lurie and his Hergesheimer understand and sympathise with the highs and lows of Joseph H.’s career.

Those interested in classifying fiction under Themes or Topics will find in this book: Writers and Real Estate; the Venality of Architects; Forgers; Writers and Benefactors; Loss; How to Write about a Child Who Died; Adultery; Glenn Gould; The Slap (not to be confused with Christos Tsiolkas’s version); Writers and $; Not Writing; the Writer’s Life; Metaphor (‘Metaphor will only get you so far’; ‘Isn’t the story told in a nutshell often the hardest to crack’; of a man painting a nude model: ‘To kiss the canvas with his gushing brush’; or, as Beckett has it: ‘No symbols where none intended’).

But Themes and Topics in fiction are of primary concern only to those ‘deficient in mere brain-power’. What is really of significance, of importance, is style. The Writing. The Geography of the Sentence as William H. Gass (another American!) hath it. Consider, for example:

Slumped in your favorite chair, with your nine drinks lined up on the side table in soldierly array, and your hand never far from them, and your other hand holding on to the plump belly of the overfed child, and perhaps rocking a bit, if the chair is a rocking chair as mine was in those days, then it is true that a tiny tendril of contempt – strike that, content – might curl up from the storehouse where the world’s content is kept, and reach into your softened brain and take hold there, persuading you that this, at last, is the fruit of all your labors …

That is from Donald Barthelme’s ‘Critique de la Vie Quotidienne’ collected in his Sadness (1972). This is from Lurie’s ‘Letter to a Silent Son’:

Well we secured the perimeter and sent up our smoke and in due course of imminent expectation those of us who were watching the sky which I’d have to say with no disregard of duty attached and I want to stress that in plainest language without qualification or exception as I hope and trust by now to be made perfectly clear …

Ah! those sentences, those rhythms, those riffs! Lurie is, to borrow a title from Barthelme’s Great Days (1979), ‘The King of Jazz’.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.