Archive

Mussolini’s Italy: Life under the dictatorship 1915–1945 by Richard Bosworth

by Judith Keene •

One Way Ticket: The untold story of the Bali nine by Cindy Wockner and Madonna King

by Marina Cornish •

Australian Security After 9/11: New and old agendas edited by Derek McDougall and Peter Shearman

by Michael Wesley •

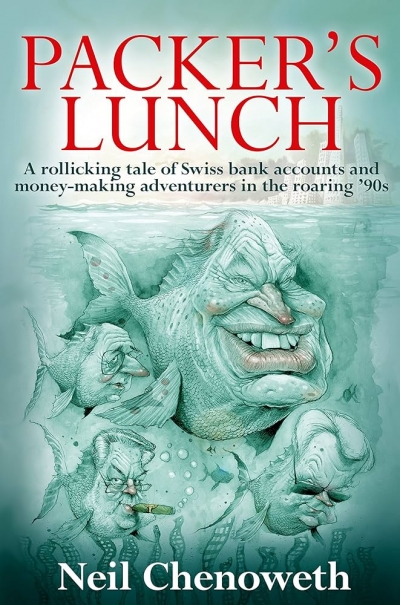

Packer’s Lunch: A rollicking tale of Swiss bank accounts and money-making adventures in the roaring 90s by Neil Chenoweth

by Peter Haig •

The kitchen vessels that sustained

Your printed books, my poems, our life,

Are fallen away. The words remain –

Not all – but those of style and worth.

The New Puritans: The rise of fundamentalism in the Sydney Anglican Church by Muriel Porter

by Philip Harvey •

Global Matrix: Nationalism, globalism and state-terrorism by Tom Nairn and Paul James

by Roland Bleiker •

Learning To Dance: Elizabeth Jolley – Her life and work edited by Caroline Lurie

by Shirley Walker •