Biography

A War of Words: The man who talked 4000 Japanese into surrender by Hamish McDonald

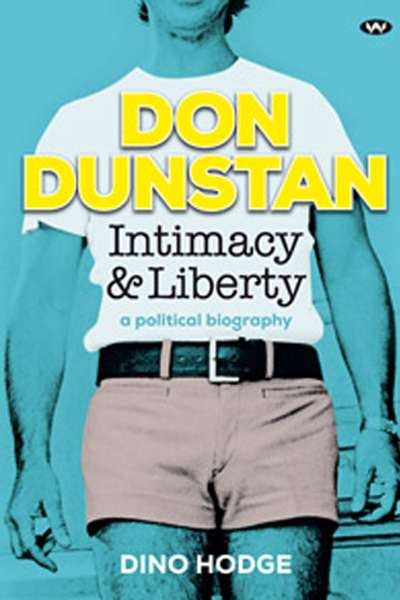

Don Dunstan, Intimacy & Liberty: A political biography by Dino Hodge

Breakfast with Lucian: A portrait of the artist by Geordie Greig

Music in the Castle of Heaven: A portrait of Johann Sebastian Bach by John Eliot Gardiner

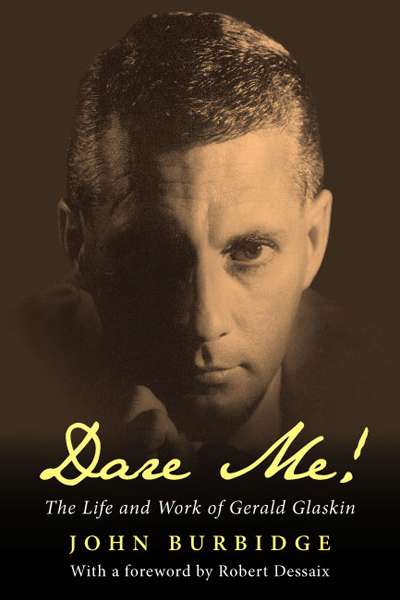

Dare Me!: The life and work of Gerald Glaskin by John Burbidge

The Literary Churchill: Author, reader, actor by Jonathan Rose

On an early spring evening in 1919, in a nearly empty cinema in the English seaside town of Lyme Regis, a slight, dark-haired figure slipped into a seat at the farthest edge of a row. From here, she would have a clear view of the profile of the youthful pianist who, sheltered behind a screen, accompanied the silent film. In white tie and tails, with her fair hair slicked down, the young musician could easily have passed for a boy. But Henry knew better. She had already extracted from the cinema’s owner the useful information that the pianist who gave such superlative performances night after night in the dark, sparsely filled hall was his daughter, Olga. The delicious ambiguity of the young woman’s appearance only added to the pleasure of her effortless improvisations. The soft, feminine form in its stiff, masculine garb was as enticing as the verve and finesse of the music itself.

... (read more)