Biography

Charles Kingsford Smith and Those Magnificent Men by Peter FitzSimons

by Peter Pierce •

Sins of the Father: The Long shadow of a religious cult by Fleur Beale

by Bill Metcalf •

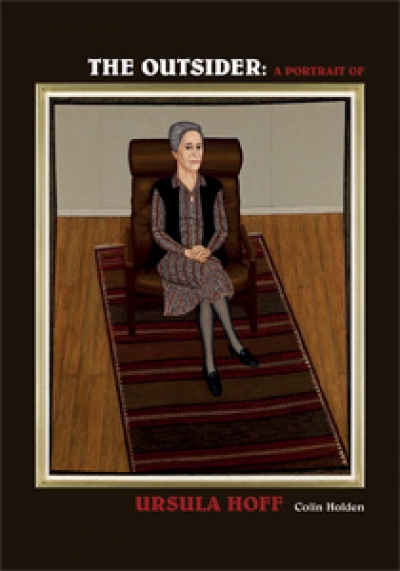

The Outsider: A Portrait of Ursula Hoff by Colin Holden

by Jaynie Anderson •

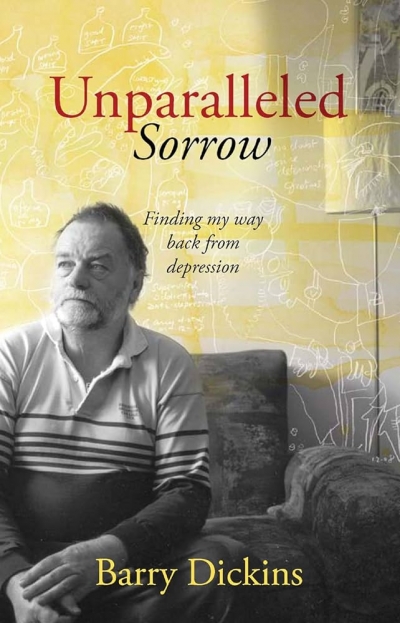

Unparalleled Sorrow: Finding my way back from depression by Barry Dickins

by Michael McGirr •

The Ghost at the Wedding: A true story by Shirley Walker

by Brenda Niall •

Vincent Buckley edited by Chris Wallace-Crabbe & Journey Without Arrival by John McLaren

by Gregory Kratzmann •