Paul Brunton

A Forger’s Progress: The life of Francis Greenway by Alasdair McGregor

While the Billy Boils by Henry Lawson & Biography of a Book by Paul Eggert

Book Life: The Life and Times of David Scott Mitchell by Eileen Chanin

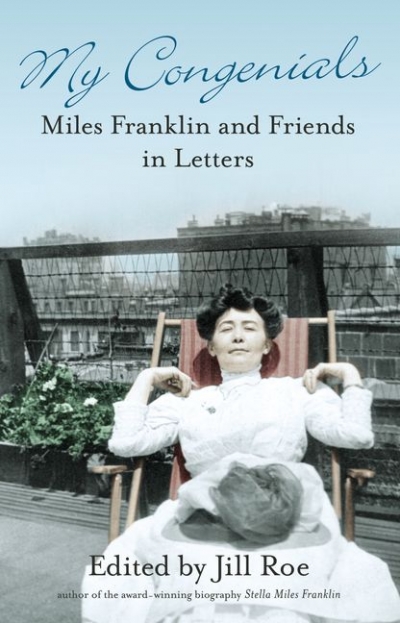

My Congenials: Miles Franklin and friends in letters edited by Jill Roe

The Diaries of Donald Friend, Vol. 4 edited by Paul Hetherington

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 325: Australian writers, 1975–2000 edited by Selina Samuels

Dennis Altman

In any given year we will read but a tiny handful of potential ‘best books’, so this is no more than a personal selection. Here are two novels that stand out: Stephen Eldred-Grigg’s Shanghai Boy (Vintage) and Hari Kunzru’s Tranmission (Penguin). Both speak of the confusion of identity and emotions caused by rapid displacement across the world. The first is the account of a middle-aged New Zealand teacher who falls disastrously in love while teaching in Shanghai. Transmission takes a naïve young Indian computer programmer to the United States, with remarkable consequences. From a number of political books, let me select two, both from my own publisher, Scribe, which offers, I regret, no kickbacks. One is George Megalogenis’s The Longest Decade; the other, James Carroll’s House of War. Together they provide a depressing but challenging backdrop to understanding the current impasse of the Bush–Howard administrations in Iraq.

... (read more)