Biography

The Feasts and Seasons of John F. Kelly by Robert Pascoe

by Michael McGirr •

Universal dictionaries are no longer possible or desirable. If we would conquer the realm of knowledge we must be content to divide it.’ Thus wrote The Times on 5 January 1885 in its first article on the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB), whose initial supplement – the first of an eventual sixty-three published over the next fifteen years – was then about to appear.

... (read more)David Golder by Irène Némirovsky & Irène Némirovsky by Jonathan Weiss

by Colin Nettelbeck •

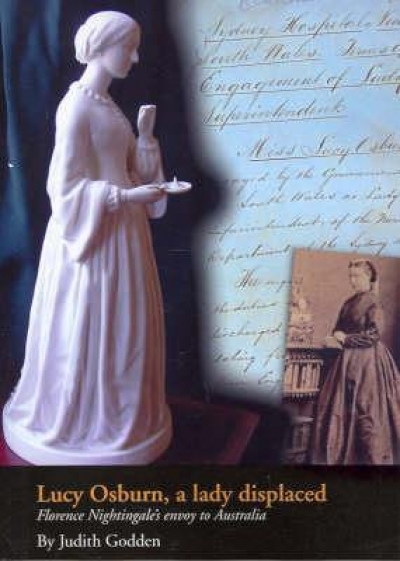

Lucy Osburn, A Lady Displaced: Florence Nightingale's envoy to Australia by Judith Godden

by Beverley Kingston •

Alien Roots: A German Jewish girlhood: from belonging to exile by Anne Jacobs

by Carol Middleton •

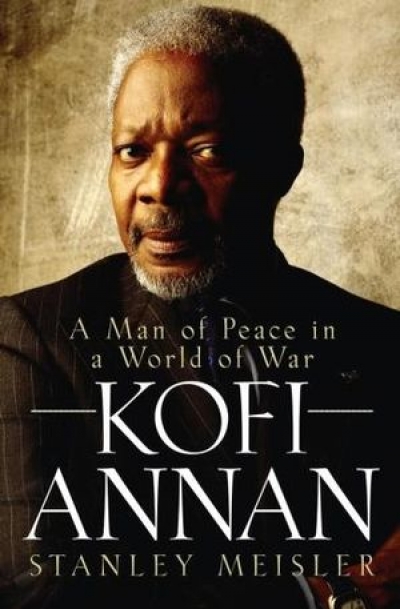

Kofi Annan: A man of peace in a world of war by Stanley Meisler

by Alison Broinowski •