The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is: A history, a philosophy, a warning

Princeton University Pressl, US$24.95 pb, 204 pp

Hope in affliction

A dubious privilege of belonging to Generation X is that your life straddles the period during which the internet went from being science fiction to settled fact of life. Take, for example, Justin Smith, the American-born, University of Paris-based historian of philosophy and science, a professor who turns fifty this year. He started out on dial-up message boards in the 1980s, saw his first HTML web page in the 1990s, and now maintains a well-regarded Substack newsletter, where, in between meditations on the historical ontology of depression and the metaphysics of onomastics, he writes with a subtle eye regarding online culture in all its manifestations.

In other words, Smith’s is a binocular vision: an effort to apply the intellectual longue durée of humanistic enquiry to a world increasingly shaped by experience of the digital. In recent years, however, the author’s early optimism about the liberatory possibilities of the internet (a catch-all term which, employing a kind of reverse synecdoche, he uses to define that tiny portion of the web that we mainly use, particularly social media) has curdled.

In a viral essay published in The Point Mag in 2019, Smith wrote:

It has come to seem to me recently that this present moment must be to language something like what the Industrial Revolution was to textiles. A writer who works on the old system of production can spend days crafting a sentence, putting what feels like a worthy idea into language, only to find, once finished, that the internet has already produced countless sentences that are more or less just like it, even if these lack the same artisanal origin story that we imagine gives writing its soul. There is, it seems to me, no more place for writers and thinkers in our future than, since the nineteenth century, there has been for weavers.

‘This predicament,’ he concluded, ‘is not confined to politics, and in fact engulfs all domains of human social existence.’

The Internet Is Not What You Think It Is expands on the implications of this darkening view. It is Smith’s attempt to explain how and why he has come to regard the internet as inimical to human thriving. It explores, with hypertextual agility and philosophic rigour, everything from the concentrated power of tech monopolies, the crimping effects of algorithmic decision making in domains as disparate as filmmaking and credit ratings, the corrosive effect of misinformation on our politics and even the grounds of our shared reality, the gamification of our online existences, and the enclosure of our attentional commons. But it does so in a novel way – by zooming out ‘to consider it in relation to its precedents, or in relation to other things alongside which it exists in a totality’.

This is a more radical manoeuvre than it looks. The internet is a phenomenon closely tied to its technological manifestations and our historical moment. Any attempt to decouple the web from the networks and protocols on which it runs seems weird, a message divorced from its medium. For Smith, however – a scholar of Leibniz, and an intellectual omnivore more generally – the internet has a prehistory old as our species:

It is … only the most recent permutation of a complex of behaviours that is as deeply rooted in who we are as a species as anything else we do: our storytelling, our fashions, our friendships; our evolution as beings that inhabit a universe dense with symbols.

Not only that: Smith even goes so far as to argue that the networked nature of the internet is not solely a human characteristic. The clicks of Humpback whales that can be heard by fellow cetaceans an ocean away. Foot-stamp telegraphs employed by African elephants. The ‘wood wide web’ in which mycorrhizal fungi colonise root systems and use fungal filaments, or mycelia, to create an underground network between trees. All these ‘natural’ networks share commonalities with human efforts, Smith argues. They suggest that ‘the internet is not best seen as a lifeless artefact, contraption, gadget, or mere tool, but as a living system’.

Smith makes a convincing argument that technology has obscured the organic origins of this universal drive to amplification, connection, augmentation, and exchange. Viewed from this perspective, even the most complex inventions, made from material wholly abstracted from their biological substance, remain instances of natural technique. We are spiders who spin with fibre-optic cable rather than protein-silk, ‘an excrescence of the species-specific activity of homo sapiens’.

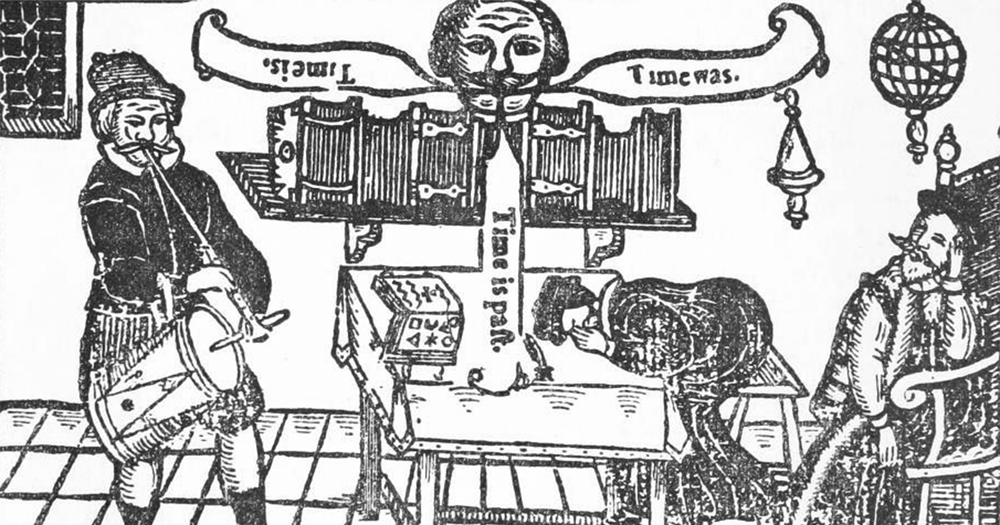

But if this potential has always existed, why only now has such ‘excrescence’ been manifested? In a chapter dedicated to the genealogy of computation and AI, Smith takes us all the way back to Roger Bacon’s thirteenth-century ‘Brazen Head’ (a kind of medieval Siri that could answer any question) via Leibniz’s 1670 stepped reckoner calculating device and Lovelace and Babbage’s nineteenth-century ‘Analytical Engine’, and suggests that even when such devices were merely fantasies of computational power or communication ability, they nonetheless opened up potential for subsequent thinkers to realise.

By 1685, Smith notes, ‘Leibniz was already envisioning a machine-aided society’, one, moreover, in which humans were assisted by machines rather than being dominated by them. This utopian potential is followed like a golden thread through the centuries to the present – call it an alternative history of the pre-internet – as a way of holding open the possibility that the internet as we currently know it might be other than it is.

Here lies the paradox of Smith’s historicising efforts. For all its broadening and deepening of the context by which we understand the internet, the book returns us to those established technological structures and networks he collectively arraigns ‘for crimes against humanity’. There is no off switch for what we have made.

The philosopher’s negative portrayal of the internet in these pages is, in most respects, an unanswerable jeremiad, thrilling for the cogency with which it identifies those aspects of online experience most inhospitable to either the growth of individual selves, or else the encouragement of civil debate intrinsic to democracy’s maintenance. Smith knows the internet is a system that slays individual attentiveness, one built from a concatenation of soul-flattening algorithms. He rightly regards social media as a perpetual grievance machine.

And yet. Though the internet ‘is the primary motor for the spread of this new system, it is very likely that whatever new sanctuaries we might yet hope to build, where the rapacious logic of this new system does not have any purchase, will also come through the internet’.

The gravest affliction we suffer, he suggests, is also our greatest hope.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.