Scott Stephens

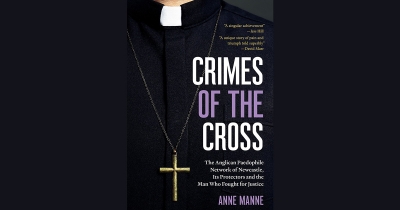

In this week’s ABR Podcast, Scott Stephens reviews a book by Anne Manne: Crimes of the Crimes of the Cross: The Anglican paedophile network of Newcastle, its protectors and the man who fought for justice. Why is narcissism a central theme for a book about child sexual abuse? Stephens writes: ‘without the capacity or willingness to be attentive to the humanity of another person’, unfathomable cruelty becomes possible. Scott Stephens is the ABC’s Religion & Ethics online editor and the co-host, with Waleed Aly, of The Minefield on ABC Radio National. Listen to Scott Stephens’s ‘Soul blindness: Clerical narcissism and unfathomable cruelty’, published in the May issue of ABR.

... (read more)Crimes of the Cross: The Anglican paedophile network of Newcastle, its protectors and the man who fought for justice by Anne Manne

This week on the ABR Podcast we consider a poetics of contemplation with Scott Stephens. In his review of Kevin Hart’s book on reading and thinking, Lands of Likeness, Stephens writes, ‘there is no desire to consume the object of contemplation; what there is, is a longing to understand’. Scott Stephens is the ABC’s Religion & Ethics online editor and the co-host, with Waleed Aly, of The Minefield on ABC Radio National. Listen to Scott Stephens’ ‘Nothing but kestrel: Kevin Hart’s invitation to read contemplatively’, published in the March issue of ABR.

... (read more)