2017 Calibre Essay Prize (Second prize): 'To Speak of Sorrow' by Darius Sepehri

‘I still have grief inside me, no matter how long my people’s been gone. I still have that grief, and tear, and rip in my heart like it happened yesterday ... Even alherntere, non-Indigenous people can feel it.’

Margaret Kemarre Turner,

Iwenhe Tyerrtye: What It Means to Be an Aboriginal Person (2010)

Tehran, April 1987: Going Under

Descending in a stream of arpeggio broken chords: as we moved through night and the vernal air down into the green earth, my mother thought she heard a children’s song on the stairs as the bombs fell cascading. Like bells, bells of Hades sounding out inverted intervals, the bombs fell interminably. The sirens that were singing sang us downward to the damp islands of the underground shelter, a honeycomb under the Tehran metropolis, buzzing with heat-maddened, with death-maddened men and women. My mother was quick with child and as she ran barefoot down the spiralling stairs she was engulfed by the yawning mouth of the desecrated earth. It was two months shy of my birth. All was opaque and suffocating. Concrete shards broke and fell from the ceiling, missiles rained down in deluge. As a whale yawning wide, trenches on the battle-front split and men were dragged into the void. Later, as I came up out of the waters, I knew this sorrow would abide. I tasted a fruit with an ashen core and I saw over all the earth ashes and soot spread abroad, veiling the stars, this shroud.

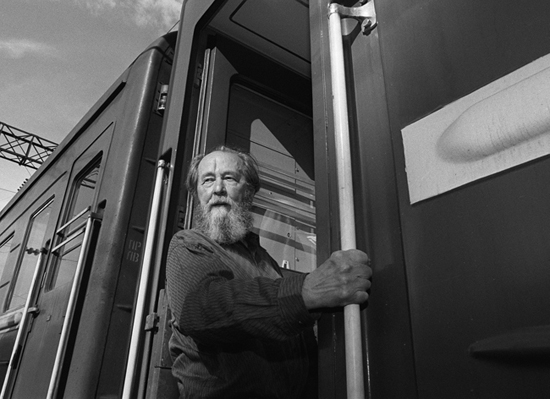

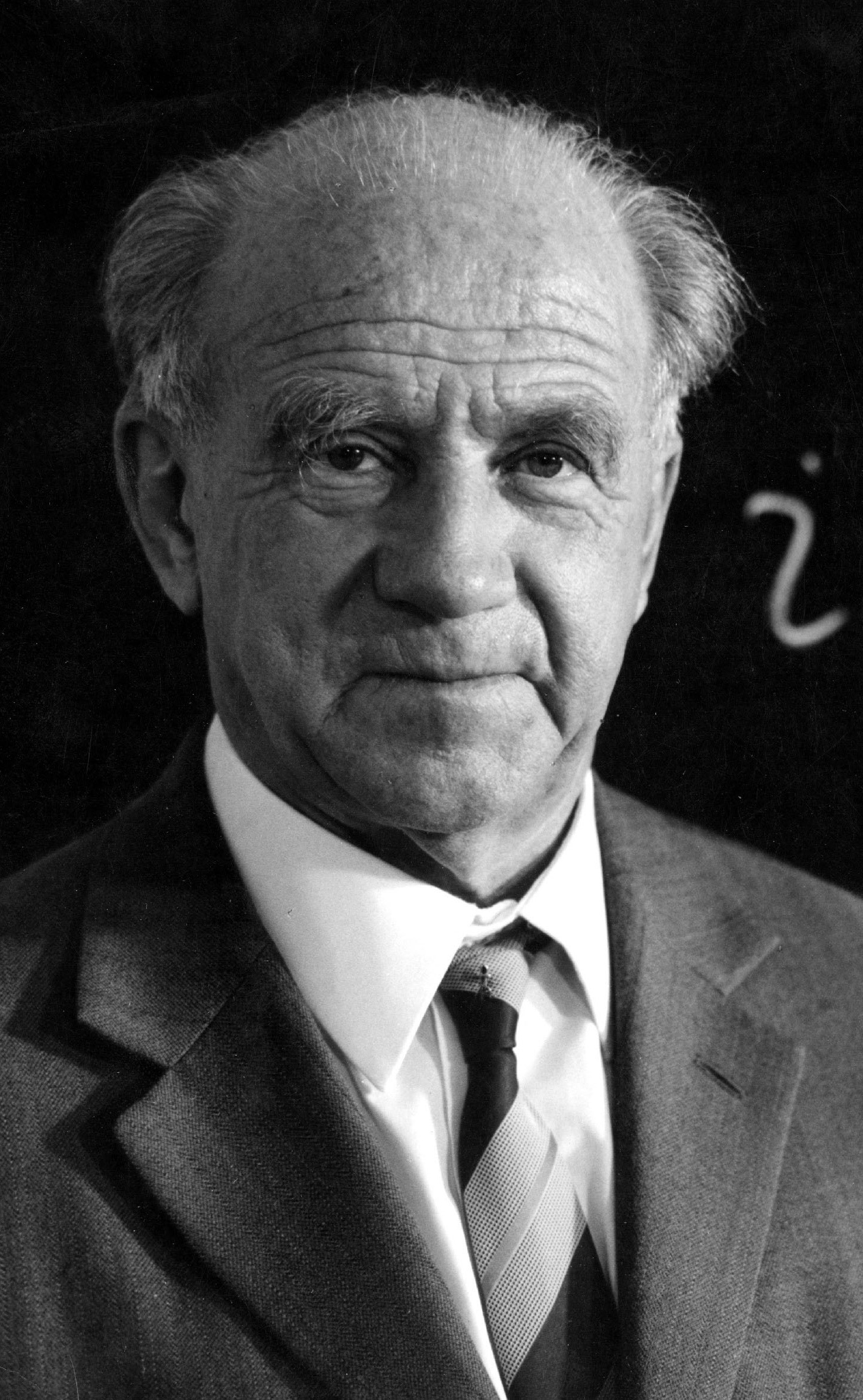

Vaslav Nijinsky, before going mad, wrote in his diaries that he felt the tremendous presence of god without fear: ‘I do not want to crack,’ he insisted, ‘but to say the truth.’ Decades later, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, driven to express his moral vision of humanity charged with responsibilities of compassion, might have said the same. Undergoing extraordinary anguish, Solzhenitsyn testified to our responses to life’s beauty and harshness. He sank into a hell but found there the possibility to realising a kind of heaven, fulfilling the desire expressed by Greek poet Odysseus Elytis: ‘I want to descend the steps, to fall into this verdant fire and then to ascend like an angel of the Lord ...’

It is little wonder that I crave depths, catacombs, the belly of the whale; that I seek nourishment like the heart-roots of Tehran’s old sycamore trees. My life began with my mother’s descent into underground bomb shelters during the ‘War of the Cities’, late in the Iran–Iraq War, when Saddam Hussein, deploying Soviet missiles, rained death on Iranian cities. Thousands of civilians, like hundreds of thousands of Iraqi and Iranian conscripts, were killed. The world watched, did nothing, and finally gave Saddam more weapons, including poison gas.

After surviving this plunge, there was a figurative one, a schooling, with millennia-old Persian poetry and music, in the inner dimension of depth, often expressing sorrow. The gift of such formative encounters arises from the reality that grief requires inwardness if it is to be more than a pathology. Inchoate in my mind – a product of this early experience of grief as soulful but transformative – was the sense that the aftermath of grief depended on the psychological, spiritual, and creative frameworks in which it takes place. Grief is best when it comes in alchemical modes. For metamorphosis to take place, we need a transformative, alchemical space presided by the psychopomp Hermes, who will lead us as he led Priam, almost destroyed by grief, to Achilles – both afterwards wholly changed.

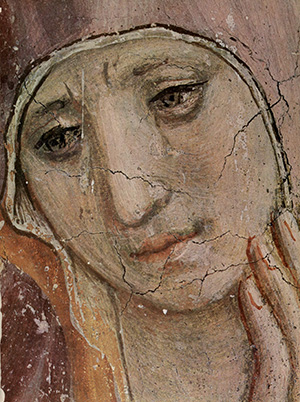

Trauernde Maria (detail) by Fra Angelico (The Yorck Project, via Wikimedia Commons) Mythologically, the descent was always to an inner space. We are familiar with these mythological descents to the underworld, katabasis in Greek. Before Odysseus in Dante’s Inferno there was Gilgamesh, Osiris, Innana, Hercules, and Orpheus; after him, Aeneas, Christ. And today? We enter the inferno with trials, losses, failures, wrongdoing in public and private, terror and trauma. Often the inferno is called depression, the black dog. Yet in Australia, what of the languages to express grief and mourning: are they accessible, appropriate? What is the function of these modes of expression in Australia? We know, despite our successes, there is enormous trauma in our history. We have made a kind of hell here, and abroad, and we cover them up. Coming from Iran, where grief is ubiquitous, it seems that only with the deaths of relatives and isolated shocking events is grief expressed in Australia. The grief with which I want to deal is not only bereavement, which some, narrowing the definition, take grief to be, though that grief gives us many opportunities for growth.

Trauernde Maria (detail) by Fra Angelico (The Yorck Project, via Wikimedia Commons) Mythologically, the descent was always to an inner space. We are familiar with these mythological descents to the underworld, katabasis in Greek. Before Odysseus in Dante’s Inferno there was Gilgamesh, Osiris, Innana, Hercules, and Orpheus; after him, Aeneas, Christ. And today? We enter the inferno with trials, losses, failures, wrongdoing in public and private, terror and trauma. Often the inferno is called depression, the black dog. Yet in Australia, what of the languages to express grief and mourning: are they accessible, appropriate? What is the function of these modes of expression in Australia? We know, despite our successes, there is enormous trauma in our history. We have made a kind of hell here, and abroad, and we cover them up. Coming from Iran, where grief is ubiquitous, it seems that only with the deaths of relatives and isolated shocking events is grief expressed in Australia. The grief with which I want to deal is not only bereavement, which some, narrowing the definition, take grief to be, though that grief gives us many opportunities for growth.

My family learned this when it lost a son and brother – my uncle – to senseless violence. He was thirty-two.

There is much to lament, including the massacres and dispossession of Aboriginal peoples, and subsequent policies of inhuman kinds, a background hum to our lives. Such brutalities are not only matters of political responsibility and reparation, they are psychic wounds that will not disappear until they are dealt with through appropriate modes of mourning. Wars followed in which men were butchered or, as with Vietnam, returned psychologically damaged. Today we note the confinement of people in offshore detention – in gulag-like conditions. The latter calls for Australians not only to engage in the clinical language of reportage, or angry expressions of opposition, but also protest voiced as lamentation, whether as essays, conversation, poetry, songs, art, letters to political representatives. Lament should not only be directed toward the far past. There is also the matter of ecological catastrophe, mass extinction of species, and the unravelling of ecosystems. Audra Mitchell calls this the ‘unmaking of being’; she argues that it needs to be experienced as more than statistics: ‘no matter how much data we collect on past and possible future extinctions, we can never have experienced extinction empirically.’

Katabasis as transformation was at the heart of Solzhenitsyn’s work. In The Gulag Archipelago (1973), he argues that grief brings moral development:

In prison, both in solitary confinement and outside solitary too, a human being confronts his grief face to face. This grief is a mountain, but he has to find space inside himself for it, to familiarize himself with it, to digest it, and it him. This is the highest form of moral effort, which has always ennobled every human being. A duel with years and with walls constitutes moral work and a path upward (if you can climb it).

Critic Dan Jacobson said: ‘Solzhenitsyn takes for granted an absolutely direct and open connection between literature and morality, art and life.’ Solzhenitsyn himself made the relationship between art and morality explicit in his Nobel lecture, when he insisted that the road to glory runs through a frank acknowledgment of despair, cruelty, and failure. The artist must inform society of ‘all that is unhealthy and cause for anxiety’.

Solzhenitsyn, in the Ekibastuz gulag, had a kindred spirit, the poet Anatoly Silin. A latter-day Myshkin, Silin declares that the human soul must suffer before it can taste the ‘perfect bliss of paradise’, and that ‘by grief alone is love perfected’. Silin had memorised twenty thousand lines of poetry. Solzhenitsyn, using a rosary, memorised twelve thousand lines of his own work. This was a theology of suffering practised by weaving together hardship with the creation of imaginative works.

What we learn from the story of Jonah, with his repeated denial of God’s instructions, is that katabasis can be avoided but keeps calling. As Joseph Campbell taught us, one may refuse the heroic journey to the transformative space and stay in town. In our success-crazed society, it is necessary to remember Icarus. Katabasis: sinking down, bottom pulled out from under us in the blink of an eye, a swift fall; leaving the world of glittering things as ashes and cinders; loss of normality, prestige, success, and order; embrace of doubt, mourning, danger, isolation.

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (photograph by Mikhail Evstafiev)

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (photograph by Mikhail Evstafiev)

I have always been distrustful of society’s disavowal of grief. Growing up Iranian, I absorbed music, poetry, art, turns of phrase and habits of mind, all of which, as the inverse of an extraordinary emphasis on beauty, stress sorrow. The grief in Persian culture comes partly from Iran’s tragic history, beginning with defeat by Muslim Arabs of Zoroastrian Persia under the Sassanian dynasty, having been weakened by long conflict with the Byzantines. After that year zero, Iran has not, apart from the odd brief exception, been ruled by Iranians. In successive waves, the Arabs, Turks, and Mongols battered the Iranian people and subjugated them, before becoming themselves Persianised.

Genghis Khan, after crossing the Syr Darya river in 1219, directed the unfathomably brutal campaigns in Transoxiana and Khorasan; between 1220 and 1221 he destroyed the grand cities of Bukhara, Samarkand, Herat, Tus, and Nishapur. According to Rashīd al-Dīn, a historian who served under Ilkhanate rule in Iran, the Mongols murdered more than 700,000 people in Merv and over a million in Nishapur. No wonder that Iranians are obsessed with their ancient past: pride in the achievements of the Achaemenids makes it a bitter cup to swallow the losses that followed. I have heard similar laments from Aboriginal people in Australia.

These calamities happened long ago, but the suffering has never gone away. Trauma, an essential signifier of our times, relates ‘present suffering to past violence’, according to Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman in The Empire of Trauma (2009), and is the ‘collective imprint on a group of a historical experience that may have occurred decades, generations or even centuries ago’. The book is a study of the condition, wholly contemporary they argue, of victimhood and its historical construction and political use. It is true that grief, trauma, and victimhood are connected in ways that are important to acknowledge. We are often told, especially on Anzac or Australia Day, that any kind of public grief over historical traumas not prescribed within established national narratives is the product of a mentality of victimhood that serves unwelcome ends. It falls to those who are fighting on the side of memory against oblivion, acknowledgment rather than denial, to insist that simply because victimhood is problematic does not nullify the reality that trauma persists vividly and tenaciously.

In his recent Monthly essay ‘Rom Watangu’, Aboriginal elder Galarrwuy Yunupingu tells how memories of European massacres in East Arnhem Land ‘are burned into our minds. They are never forgotten. Such things are remembered. Like the scar that marked the exit of the bullet from my father’s body.’ A few hundred years, even a thousand, may not allow suffering to fully dissipate. Trauma, as Yunupingu attests with his metaphor, is passed down first through the body, beginning, I have always believed, with the women who pass the effect of stress (physically, as cortisol), screams, and terror to the next generation through the closeness of the womb.

Christmas 1993, Sydney

When I was six my uncle was murdered. Masoud was his name. He was thirty-two. Beloved on the earth.

My grandmother wanted to tear the earth with her teeth, unwind the white bandage. Her son, made in ecstasy.

Agony that lurched drunken and raving through the streets, rabid dogs and dust under frantic hooves.

There was something about the father of the Flanagans who lived four doors down from our Brisbane home that reminded me of my mother. Like Iranians, the Irish have a tragic conception of history, which they sing, dance, chant, and keen. After centuries of subjugation and occupation, it is inevitable that the Irish – Australian historian Patrick O’Farrell has called them the ‘archaic, melancholy, humorous, religious, contradictory and occasionally indomitable Irishry’ – know how to mourn. In the now extinct practice of ‘keening’, keeners (bean chaointe) howled stock poetic elements in lamenting melodies over the dead body, both during the funeral and at the place of interment. Today, similar rites still occur at Iranian funerals, where hired singers, skilled at manipulating emotions, weave the names of the deceased into stock poems and sing them with great intensity. Heated singing and crying for deceased relations has been carried out by Aboriginal women on this continent for generations.

In the Iranian and Irish context, lamentations at the deaths of Indigenous heroes and Abrahamic saints and martyrs, ritualised Catholic and Shia mourning events, are extreme and sentimental, as well as regenerative; they can bring the energy of cataclysm and breakdown required for true homeostasis. Lamentation for the Shia Imams, especially martyred Hossein, known as rowze khani, are Dionysian and Saturnine. Decorum and restraint ensure things run well, but they can lead to stagnancy. Popular expressions of sorrow ensure that a language of mourning is available to people; one can slip into grief quickly if need be. My Iranian ancestors have sung grief, and so can I. Hafez, the greatest of Persian poets, is the poet of ecstasy and sorrow, in equal measure.

The exploration of grief uncovers persistent distrust of its open expression. Soon after Australian settlement, the British regarded their pragmatism as being tied up with habit and perseverance, while the Irish were seen as wallowers or even savages. The grief they brought with them from the Old Country would go on to affect Australian society and writing, as exemplified by the sorrow of oral ballads. In David Malouf’s The Conversations at Curlow Creek (1996), we find this description of Ireland: ‘Salt and sorrow over the fields, a sad country; mournful, made human by the long sorrows it had endured, the sorrows yet to come.’ The phrase itself reads as lament and locates grief in the landscape itself as produced by human activity that ‘saddens’ and shapes that landscape. Malouf’s lyrical sentence implies that grief can help to make us more at home in the world.

Deborah Bird Rose reminds us that country to Aboriginal people is spoken of as people are: ‘People say that country knows, hears, smells, takes notice.’ And what to do when country has been hurt? How do we sing that sadness along with Aboriginal people? If we have no ‘knowledge of grief’, as Rilke calls it, what will we say, how will we cry out?

In the stories of recent arrivals in Australia, we often find that grief comes as a double exclusion from the old country and the new. ‘I cannot claim to belong here fully,’ writes Andrew Riemer writes in his memoir Inside Outside (1992); he arrived in Australia as an eleven-year-old in 1947 from a devastated Hungary. ‘No matter how thoroughly you have been absorbed by your adopted society ... your otherness cannot be expunged.’

The dolour of Kenneth McKenzie’s The Young Desire It (1937) reads as the ‘perilous tension’ between his loss of an idyllic childhood and his alienation at the boys’ school where he is tormented. This liminality is the true meaning of Gethsemane, where Christ found everything he had depended on slipping from beneath him, his mission shattered, his dozing disciples – how awful the sound of their untroubled sleep – unable to comprehend his feelings. Why then, do Christ’s brokenness and vulnerability at Gethsemane often seem so distant from Christian spirituality?

Something similarly telling has occurred with the Persian Sufi poet Rumi, whose popularity has reached extraordinary heights in the West, especially the United States. In much of the English-speaking world, largely due to the work of Coleman Barks, Rumi is prized for his joyfulness and ecstatic utterance, not for his lamentations, as in the famous opening to his epic Masnavi: ‘Now listen to this reed-flute’s deep lament / About the heartache being apart has meant.’ As Rumi scholar Franklin Lewis has pointed out, Rumi, like Hafez, is a poet ‘of overpowering longing, trying to grope through his shattering sense of loss – loss of Shams and alienation in the material world from the spiritual source’. The grief in Persian poetry and music, so familiar from my childhood, is not only a memory of harsh experiences but is in fact archetypal, having to do with metaphysical separation from ultimate reality, and the tragedy of everything not fulfilled, with our incompleteness and propensity to fall short of what we might be, our brokenness and un-wholeness. ‘Life is, in itself, forever a shipwreck,’ said José Ortega y Gasset, as he packed his bags to flee a broken Civil War Spain.

My uncle went to the morgue to identify his brother’s body. The police pulled back the cloth only partly, for Masoud’s face was disfigured. They took my uncle outside and asked him to sign for his brother’s death. He refused to acknowledge that his brother was dead. They took him back into the room, showed him the body. Outside, they asked him to sign. Still he wouldn’t agree. The police looked at each other and at their feet.

Last night my uncle made Masoud dinner.

Deborah Bird Rose, professor in environmental humanities, has introduced the idea of ‘double-death’, in which too many losses in an ecosystem also destroy the process of resilience and thus unravel the relationship between life and death. Rose believes this is an ‘open secret, and an open wound’ we are struggling to witness. ‘Perhaps,’ she reflects, ‘we lack awareness of the beauty of death, and therefore fail to perceive that it is being violated.’

One kind of double death that Rose defines is the ‘unmaking of country, unravelling the work of generation upon generation of living beings’. Mourning the violence inflicted on the land is hard, serious work. Death belongs to the whole community, and dying is not only for the dead but for those who remain to mourn and remember and to sing the dead to their proper place. When mass killings and atrocities occur, according to James Hatley, they are acts of aenocide: ‘a murdering of generations’. What is killed is thus not only living beings but knowledge itself. It was perhaps against such violence that Oodgeroo wrote: ‘Let no one say the past is dead. / The past is all about us and within. / Haunted by tribal memories, I know.’ Here, the poet’s ‘I know’ itself grieves, and is a work in grief of the highest nobility.

Anthropologists Luke Godwin and James Weiner write that ‘places where Aboriginal ancestors were killed as a result of frontier violence constitute one of the most important and impassioned categories of contemporary “sacred” places for all Indigenous communities in Australia’. In contrast to this is what is called ‘dark tourism’, travel to sites connected to death or disaster or atrocity or just general strangeness. There is no mandatory attempt to mourn the suffering visited on the site. On www.dark-tourism.com, under the Australia section, one reads that Uluru could be a site for dark tourism because it ‘generates a somewhat spooky aura’ and because of the death of Azaria Chamberlain. If this is not enough for them, ‘dark tourists’ have the choice of grave tourism, genocide tourism, prison/persecution site tourism, or Cold War tourism.

Gulag tourism: if you visit Ekibastuz in the Pavlodar oblast, do you hear the bawling and yowls of mortification, forlorn curses of wrecked men, prayers of reborn men, the sound of the Redeemer creating upon pummelled flesh and mutilated skin a wealth of love?

Solzhenitsyn accepted the descent, did not crack, and spoke the truth.

I believe this dark tourism, griefless, is often a kind of torture fetishism. As you step into this room you’ll see where they pulled fingernails out ... It is of a piece with recent genres of entertainment like ‘disaster porn’ and ‘torture porn’, which depict trauma but find no meaning in it, a traumatising process.

Lake George (photograph by Darius Sepehri)

Lake George (photograph by Darius Sepehri)

In major cycles of Irish mythological tradition, grief and suffering unmourned bind our spirits to the earth and curb its progress. Perhaps that’s why I went to Weereewa, or Lake George, as it was named by Lachlan Macquarie in 1820. The lake, twenty minutes from Canberra, was two-fifths full and rapidly evaporating. This wasn’t dark tourism, though with the many drownings and the Aboriginal story that the water drains into the other world, the designation might be appropriate. Rather, I went there to grieve my uncle, who used to throw me high into the air and buy me iceblocks. No one has ever truly recovered from his killing, and no one will. The sky is huge here, a view to infinity. I wanted my uncle’s death to fill the sky from horizon to horizon like the angel Gabriel visiting Muhammad.

The vast expanse seemed like the plains or Russian steppes. Shiraz, where my people come from, is on the Iranian plateau and offers vast panoramas. In pre-European times, Weereewa, which means ‘bad waters’ due to the water’s fast arrival and disappearance, was a meeting place. According to Canberra historian Ann Jackson-Nakano, ‘different parts of the lake marked the furthermost frontier for a number of hunter-gatherer groups whose main territories stretched much further afield’. According to the Ngunawal people, Budjabulya is a creator spirit that lives in the lake, which they also call Lake Ngungara. The lake can become completely dry and then refill, they say, because of Budjabulya, who gives when he is respected and takes away the food supply and the water when he is angry.

I take this story seriously, though I am far from it and have probably mistold it. I am familiar from Persian culture with the notion of the place of human beings as the bridge, or pontifex, between heaven and earth. Living in such a ‘pontifical’ way, we stay connected to our origins, and we have a centre. We live on the outside of a circle in the world, but so long as we remain a bridge we can dive inward, downward, to the core, the heart of things. Today, by contrast, we live as Promethean creatures, having tried to misappropriate the powers of the ancestors and of the divine realm. Knowing that Aborigines saw the role of humans as intermediaries, custodians, makes me feel closer to worlds that otherwise feel so inexplicable. There is a couplet of Hafez that I love to recite in Persian:

Like a compass, I was circling with ease on the circumference of things.

Like a point I was pulled into the centre by the cycle of time.

Near the Quaker retreat centre at the lake, called Silver Wattle, a stone labyrinth has been erected. As I walked through it, spiralling in and out, I was drawn inwards, as are all those who walk labyrinths for healing and meditation. Labyrinths are for many a space in which to reflect on the joys and challenges of life, and on mortality itself; walking inwards, one may take sorrow into the centre, where one can stop and breathe, before returning to what awaits in life. The grandeur of the lake, which has the aspect of limitlessness that I love, also opens one to mortality. I thought of the Celtic triskelion symbol, which is of three interlocking spirals, each with its own centre. Let this be a model, I said to myself as I walked the labyrinth. Let me know the beauty of Persian, Western, Aboriginal traditions, and learn from them all.

Writers, who spiral in and out and who are our bridges between worlds, have often found beauty and truth after diving downwards. There is James Agee, for instance, who underwent a katabasis to write Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), the Fortune report that featured Walker Evans’s legendary photographs of Alabaman cotton farmers. Both men left New York, where they were known and celebrated, and lived with impoverished sharecroppers. Agee plunged into the farmers’ world; living with them in houses that slept three, four, or five to a room. Agee’s own suffering connected him to that of others. Famous Men is full of Agee’s extravagant excesses, his volcanicity and verbosity. After a preface that seems Melvillean in its windings, self-referentiality, and facetiousness, Agee takes three pages to describe a sharecropper family falling into a deep sleep. The language of exaltation is reminiscent of the King James Bible and Elizabethan theatre. The first sentence is pure gravity: ‘The house and all that was in it had now descended deep beneath the gradual spiral it had sunk through; it lay formal under the order of entire silence.’ This incantatory style lasts until the last sentence of the section: ‘There was now no further extreme, and they were sunken not singularly but companionate among the whole enchanted swarm of the living, into a region prior to the youngest quaverings of creation.’

Pensacola Lighthouse spiral staircase (Wikimedia Commons)

Pensacola Lighthouse spiral staircase (Wikimedia Commons)

Those who want to write about grief and trauma can learn much from Agee, not by copying his style but by noting how he makes use of the characters. Using prose at such a high level, imparting such grandeur and majesty while depicting poor hapless workers and animals going to sleep, creates an ambience that is at once stately and vigorous. If the vigour mirrors the farmers and their workhorse stamina, the grandeur of voice brings what straight reportage could not: a sense of dignity. The gravitas of Agee’s writing, sombreness strengthened by sadness, gives characters full-bloodedness and puts them our level: we can experience grief without condescension or facile pity. Agee’s autobiography, A Death in the Family (1957), which traces the effect of his father’s death in an automobile accident, is one of the most visceral depictions of grief in writing: ‘Mary meanwhile rocked quietly backward and forward, and from side to side, groaning, quietly, from the depths of her body, not like a human creature but a fatally hurt animal.’

In Brisbane, when our house was heavy with silence, my mother would play traditional Persian music. In the afternoon, when the subtropical air was tiresome, the dirge-like voices got under my skin. The plaintive singers – revered names like Shajarian, Banān, Eftekhari, Shahram Nazeri, Marzieh – expressed a kind of ache from the deepest parts of the soul. The grief in traditional Persian music is not mere psycho-emotional affect. It is contemplative; one enters a meditative state. Shajarian, greatest singer of Persian traditional music, has said that the power of vocal singing such as his – avaaz in Persian – lies in its ability to make the listener go inward. The sadness is about tamarkoz, concentration, and motamarkez shodan, becoming centred in oneself. Much of Persian traditional music, and nearly all of avaaz, is interior. Its close links to Sufism and musicians either initiated into Sufi orders, or at least cognisant of the main principles of Sufism, have allowed Persian music to maintain an equilibrium between ecstasy and grief. I understood early, with such a schooling in grief and depth, that at the far edges of experience you have to grieve before you can praise and enjoy. As Hafez says:

May the world never be devoid of the lovers’ lamentation

For it has a joyful sound and a cheerful melody.

The language of sorrow and grief is the language of absence, distance, separation, calamity, and affliction, but also of upheaval or reversal of the order of things. So the song ‘Morgh-e Sahar (Bird of Dawn)’ that is Shajarian’s signature piece, performed for years without exception at the end of all his concerts, is a cry for justice that calls for increasing lamentation and the smarting pain of the wound.

Morning bird, mourn, further renew my pain.

With a sigh that rains fire, break this cage and overturn it.

Grief and bidad, the cry for justice, go together. For millions of Iranians within and without Iran this is a natural language, the language that unites sorrow and lament with a narrative of redressing wrongs.

None of which is found in the books of Daniel Ladinsky, a non-speaker of Persian who claims to translate Hafez but who reinvents every poem in his own words, removing Hafez’s poetry from its historical, cultural, and spiritual roots. Unfortunately, this work of charlatanry has sold millions of copies. A similar hoax was carried out in 1994 in Marlo Morgan’s Mutant Message Down Under, a best-seller in which the American author claimed to have met a non-existent group of Aborigines who charged her with communicating their message – since they were, they told her, choosing voluntary death as a tribe. Both of these acts of cultural vandalism were successful on a popular level because of the widespread general ignorance of spiritual traditions of Aboriginal Australians and the Persian mystical tradition, which is rooted both in Islam and pre-Islamic Iranian esoterism. Anyone who wants to translate Hafez should recall Yeats’s pungent line about creativity brewing up alchemically out of ‘old kettles, old bottles, and a broken can’. Needless to say, the pain of the Aboriginal people is utterly extirpated in Morgan’s book.

But there have been cultural exchanges between Australia and Iran that have been based in nobler principles. A shining but little-known example is Judith Wright’s reading of Persian poetry and of Hafez. This engagement lasted for decades and influenced Wright’s work. She wrote a dozen of her last poems in the form of the ghazal, common to Persian, Arabic, and Urdu literature. Like a bookend, ‘The Shadow of Fire: Ghazals’ sits at the end of her last collection, Phantom Dwelling, published in 1985. Wright’s transposition of the ghazal into Australian writing is dynamic. In the ghazal ‘Pressures’, she reconciles grief and ecstasy like Hafez, but rather than using stock images, as Hafez does, Wright makes the ghazal operate in a modern poetic practice by using concrete ones. One couplet has a beautiful metamorphosis: ‘Brown butterflies strike my window-pane. / When I get up to look they have always become dead leaves.’ Other couplets describe the accumulating weight of age, necessitating a slowing down under ‘Gravity’s drag, time’s wear’. The ghazal ends: ‘Blood slows, thickens, silts – yet when I saw you / once again, what a joy set this pulse jumping.’ As in Hafez, we have many couplets expressing sorrow, followed by a last couplet with another voice intruding. Wright’s joy that sets the thickened, silted blood jumping echoes the importance in Hafez of seizing the moment, even in grief, embracing reunion with the beloved (either earthly or divine). Hafez dwells repeatedly on the broken nature of life and the inevitability of pain and sorrow, but resists total pessimism. Odysseus Elytis said a similar thing of the poetry of his compatriot and contemporary, Giorgos Seferis: ‘Yes, he is somber, but he never vilifies life. He has that respect toward life which has existed in Greece ever since antiquity.’ Albert Camus, in his anguished essay ‘Helen’s Exile’ (1948), also contrasted Greek knowledge of despair (which came though beauty, he believed) with the modern age, which, in contrast, ‘has fed its despair on ugliness and convulsions’.

Mainstream news and media feed us despair and make grief impossible. News cycles encourage hatred, outrage, paranoia, titillation, and blame. Mainstream entertainment can be even worse. Hollywood, according to the documentary Reel Bad Arabs (2006), has depicted Arabs and Middle Easterners as malicious ever since its creation. With the exception of Vadim Perelman’s House of Sand and Fog (2003), I have never seen a Hollywood film that showed Iranians as real people who hurt.

‘Film is an empathy machine,’ Roger Ebert was fond of saying. Not necessarily. Films can make us worse. Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained (2012) presents a narrative that purports to be an examination of slavery and black suffering, but instead has so much to do with an unbridled revenge fetish, a recurring theme in the director’s work.

Sometimes, we find black poets who can conjure up that suffering without explicitly mentioning instances of historical cruelty. Consider, for example, the serene utterance of Langston Hughes in his well-known poem ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’: ‘I’ve known rivers / Ancient, dusky rivers. / My soul has grown deep like the rivers.’ After naming four rivers connected to black and human history, the poet’s refrain, his ‘I’ve known’ – calm and robust like Oodgeroo’s ‘I know’ – is once again a force of witness against forgetting, and the merging of landscape, memory, and implicit grief, as in Malouf’s ‘mournful country’, shows us that writing has the power to locate grief in the world as well as within the poet’s self.

That is the power of writing, but meditative cinema has related powers. The best two films I have seen that mourn trauma are Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light (2010) and The Pearl Button (2015). Both films use the beauty of the cosmos – stars, water, ocean – to enfold grief in something that can bring healing when touched through narrative. Since they deal with the extermination of indigenous Americans and Chile’s troubled history, they are relevant to Australia. The success of both countries is built on blood and bone beneath our houses and cities.

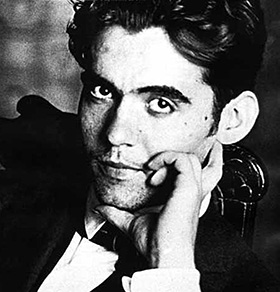

Federico García Lorca, visiting New York in 1929, was shocked by its ‘extra human architecture, its furious rhythm, its geometry and anguish’. In Poet in New York (1940), alongside poems raging against the economic injustice he saw there (particularly the marginalisation of black communities), we find biblical lamentations like the electrifying, baroque defiance against animal slaughter in ‘New York: Office and Attack’, which begins unforgettably:

Under the multiplications,

a drop of duck’s blood;

under the divisions,

a drop of a sailor’s blood;

under the additions, a river of tender blood.

Federico García Lorca (Flickr)Lorca’s personal katabasis, his anguished experience of the city, was directed to an examination of the blood lying beneath the city’s image of itself as a symbol of achievement. The lines are high-voltage, but this is grief work. It passionately mourns forgotten and ignored suffering, and pays respect back to the disrespected. At the end of the poem, like Christ in Gethsemane, Lorca offers himself ‘as food for the cows milked empty’. Little wonder that his lament for bullfighter Ignacio Sánchez Mejías makes Auden’s elegy for Yeats seem tepid. Consider this passage from therapist Francis Weller on the wildness associated with deep grief: ‘Grief is subversive, undermining the quiet agreement to behave and be in control of our emotions. It is an act of protest that declares our refusal to live numb and small. There is something feral about grief, something essentially outside the ordained and sanctioned behaviors of our culture.’

Federico García Lorca (Flickr)Lorca’s personal katabasis, his anguished experience of the city, was directed to an examination of the blood lying beneath the city’s image of itself as a symbol of achievement. The lines are high-voltage, but this is grief work. It passionately mourns forgotten and ignored suffering, and pays respect back to the disrespected. At the end of the poem, like Christ in Gethsemane, Lorca offers himself ‘as food for the cows milked empty’. Little wonder that his lament for bullfighter Ignacio Sánchez Mejías makes Auden’s elegy for Yeats seem tepid. Consider this passage from therapist Francis Weller on the wildness associated with deep grief: ‘Grief is subversive, undermining the quiet agreement to behave and be in control of our emotions. It is an act of protest that declares our refusal to live numb and small. There is something feral about grief, something essentially outside the ordained and sanctioned behaviors of our culture.’

Many Spanish-language poets from the early twentieth century understood the ‘feral’ nature of grief. Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo, Miguel Hernández: their voices have bite, a ferocious energy that is sorrowful and defiant. In Germany, Georg Trakl wrote from a similar anguish, using startling images instead of a confessional voice. We are nourished by the grief in Hart Crane, George Herbert, Kathleen Raine, Judith Wright, Francis Webb. We need elegists and lamenters and keeners, we need earth-grief, and we need to weep as a family.

Psychic wounds, as Edmund Wilson noted in his study of the Philoctetes myth in The Wound and the Bow (1941), bestow on artists immense creative prowess. Philoctetes is both banished to the edge and sought after by his fellow Greeks. The symbolic meaning of the Sophocles story is that Philoctetes is needed precisely because he knows suffering and anguish. One who is thus enclosed in the solitude of heavy grief but connected to the community, if he were alive today, would dance the Zeimbekiko, a Greek folk dance performed solo, improvised to a slow time signature. The dancer is surrounded by friends. Arms are held out wide, like Christ, like an eagle slowly circling, like Agee’s regal prose giving voice to tribulations. The modern Greek poet Yiannis Ritsos, in a poetic monologue consisting purely of Neoptolemus persuading Philoctetes to return with him to Troy, has Neoptolemus speaking of a full moon seen from a ship that makes all the fighters onboard stare motionless and ‘bewitched, as if already dead and immortal’. Then they begin to yell and make vulgar gestures ‘perhaps to forget that moment, that understanding, that absence’. As Spanish poet Antonio Machado put it, we have a ‘fear of going down’. Yet turning away from the reality of our fragility and mortality, and leaving sorrow unexpressed, weakens our power to praise. MartÍn Prechtel, a First Nations Canadian man trained in the Tzutujil Maya shamanic tradition, has written exquisitely on grief. He insists that grief is also praise, ‘because it is the natural way love honors what it misses’.

I think of Persian words when I read Margaret Kemarre Turner talking about the word Alwharpe, which means a sadness intertwined with separation from the Land: ‘If you’re sad or something, the Land just urges you, and brings you back and encourages you to go back. Because it’s got a sort of touching.’ In Persian, grief has similar visceral verbal force, with the nouns for sorrow gham or ghosseh needing to take the verb khordan, to eat, in order to form the verbs. So grief is eaten in the Persian context. Reading Turner and others, I think Aboriginal people know that sorrow and suffering sit in the body, in the chest, under the rib cage, in the liver and guts and the quivering torso. Healing comes first from the body, dancing Zeimbekiko: each of us taking the hero’s journey alone, with the communal encouragement. Hence the power of recited poetry, using breath, body, and rhythm to dance with language the grief trapped inside in the cells.

December 1999

After moving from Brisbane to Sydney, I had a dream. Faint, fatigued, dead on my feet, weak as sand and bathed in sweat, I walk across the Sydney Harbour Bridge and at the other shore I am in Shiraz, under the northern stars in the dry night air. I am atop the flat roof, where mattresses are laid out to sleep. My family are there, under countless numbers of stars studded in the clear white sheet of the sky. Masoud my beloved uncle is there, no shroud or cloth on him. The celestial vault turns around the earth, the air is sweet, and I am light and clean and newborn.

Darius Sepehri’s essay was placed second in the 2017 Calibre Essay Prize. Darius was born in Iran and moved to Australia at the age of five. He has an abiding passion for Persian culture and poetry. He is a researcher and writer at the University of Sydney in the Department of International and Comparative Literary Studies, where he is completing a doctoral thesis. He has published translations of Hafez and a long essay on the influence of Persian poetry on Judith Wright in Southerly.

The Calibre Essay Prize, created in 2007, is Australia’s premier essay prize. Calibre is funded by Australian Book Review. Here we gratefully acknowledge the generous support of ABR Chair, Mr Colin Golvan QC, and our many ABR Patrons.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.