A survey of environmental writing

Kim Scott

Bill Gammage, in The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia (2011), shows fire being deployed across the continent with a complexity and skill ‘greater than anything modern Australia has imagined’. He explains why colonists spoke of a land like ‘a gentleman’s park, an inhabited and improved country’. Controlled fire created a ‘mosaic of grass and tree’, of ‘springs, soaks, caches and wetlands’ that channelled, persuaded, and lured prey in predictable ways. Thus Indigenous cultures enabled abundance, and ‘voluminous and intricate’ spiritual and creative practice.

Bill Gammage, in The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia (2011), shows fire being deployed across the continent with a complexity and skill ‘greater than anything modern Australia has imagined’. He explains why colonists spoke of a land like ‘a gentleman’s park, an inhabited and improved country’. Controlled fire created a ‘mosaic of grass and tree’, of ‘springs, soaks, caches and wetlands’ that channelled, persuaded, and lured prey in predictable ways. Thus Indigenous cultures enabled abundance, and ‘voluminous and intricate’ spiritual and creative practice.

Kim Mahood

My nominated book is The Night Country (1971), by American anthropologist Loren Eiseley. I first encountered Eiseley’s essays in the early 1980s and was transfixed by his capacity to combine the personal, the psychological, the metaphoric, the poetic, and the scientific in prose of imaginative reach and literary beauty. His essay ‘The Creature from the Marsh’, in which he ponders the footprint of a transitional form of human, only to realise that it belongs to him, locates our flawed and aspirational species at the heart of the natural world.

Philip Jones

Snugglepot and Cuddlepie (1918), written and illustrated by May Gibbs, helped form my childhood notions of the environment. Perhaps there are two reasons. First, Gibbs proposed a connected, self-sustaining world of plants and animals in which humans played a rare but destructive role. Secondly, the book conveyed the idea that the bush harbours wonderful secrets, often on a minute level; one should tread lightly and listen.

Snugglepot and Cuddlepie (1918), written and illustrated by May Gibbs, helped form my childhood notions of the environment. Perhaps there are two reasons. First, Gibbs proposed a connected, self-sustaining world of plants and animals in which humans played a rare but destructive role. Secondly, the book conveyed the idea that the bush harbours wonderful secrets, often on a minute level; one should tread lightly and listen.

Andrea Gaynor

The Death of a Wombat (1972), Ivan Smith’s genre-defying work, emerged from an award-winning 1959 ABC radio program by Smith; Wren Books approached Clifton Pugh to provide illustrations for the book. My great-grandmother gave me a copy for Christmas when I was six years old. I was enthralled by the vulnerable beauty of its outback, and distressed at the human carelessness behind the cataclysmic bushfire that inevitably, agonisingly, claimed so many animals’ lives.

Martin Thomas

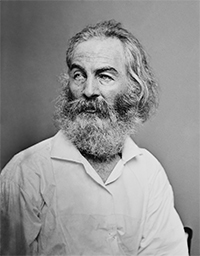

Walt Whitman (photograph by Mathew Handy, Wikimedia Commons)‘Now I am terrified at the earth!’ wrote Walt Whitman. ‘It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions.’ These lines, dear to gardeners everywhere, appear in ‘This Compost’, a homily to nature’s capacity for regeneration. Whitman’s attentiveness to the cycles and rhythms of the natural world is a constant inspiration. The cities, as much as the forests and prairies, fuelled his environmental curiosity. ‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’ is a poem that grows inside you, rocking gently to the tidal flows that underlie the daily commute.

Walt Whitman (photograph by Mathew Handy, Wikimedia Commons)‘Now I am terrified at the earth!’ wrote Walt Whitman. ‘It grows such sweet things out of such corruptions.’ These lines, dear to gardeners everywhere, appear in ‘This Compost’, a homily to nature’s capacity for regeneration. Whitman’s attentiveness to the cycles and rhythms of the natural world is a constant inspiration. The cities, as much as the forests and prairies, fuelled his environmental curiosity. ‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’ is a poem that grows inside you, rocking gently to the tidal flows that underlie the daily commute.

Danielle Clode

It was certainly the books of childhood that germinated my interest in the natural world. But one book stands out: W.J. Dakin’s Australian Seashores, posthumously published in 1952, updated by Isobel Bennett and Elizabeth Pope. For forty years this book has directed my steps along Australia’s coasts, encouraged my first forays into biology, shaped my studies, and inspired my writing every page remains a fascinating dip into a world that lies beneath our feet.

James Bradley

There aren’t many books that I can honestly say have changed my life, but Barry Lopez’s Arctic Dreams (1986) is one of them. Its luminous prose and hushed reverence for the landscape embody an understanding not just that there are other ways of imagining a landscape and our relationship to it, but of the fact that attentiveness to the particular is an ethical act in itself. It’s an extraordinary, beautiful, transformative book and one I continue to value immensely.

There aren’t many books that I can honestly say have changed my life, but Barry Lopez’s Arctic Dreams (1986) is one of them. Its luminous prose and hushed reverence for the landscape embody an understanding not just that there are other ways of imagining a landscape and our relationship to it, but of the fact that attentiveness to the particular is an ethical act in itself. It’s an extraordinary, beautiful, transformative book and one I continue to value immensely.

Alan Atkinson

Lately, there has been a wonderful rush of books connecting the old concerns of the Green movement with everything else important to humanity, from Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs the climate (2014) to Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement: Climate change and the unthinkable (2017). But note especially Pope Francis’s Laudato Si’ (2015), where questions of environmental damage and social justice are stitched together with geniune awe and, I think, perfect economy.

Ashley Hay

My tipping point was This Overheating World, an edition of Granta edited by Bill McKibben in 2003. Published fourteen years after ‘The End of Nature’, McKibben’s own first mighty global warming article, it embedded this issue in my sense of the world particularly pieces by Philip Marsden and Matthew Hart, and McKibben’s introduction. Fourteen years later again, the sorrow and frustration in that introduction remain shockingly germane. ‘Hardly anyone has fear in their guts,’ McKibben wrote. In some places that’s so, even now, as the planet gets hotter and hotter.

Grace Karskens

A lightbulb moment of discovery came with Tom Griffiths’s Hunters and Collectors: The antiquarian imagination in Australia (1996). It’s a brilliant, labyrinthine, landmark book about how Australians imagined and created their histories both human and environmental. Chapter Twelve takes readers into wilderness landscapes and reveals them to be peopled, and storied, after all. Why do conservation campaigns so often deny the intimate relationships between humans and the non-human world? Tom’s phrase ‘bleeding sepia into green’ has stayed with me.

A lightbulb moment of discovery came with Tom Griffiths’s Hunters and Collectors: The antiquarian imagination in Australia (1996). It’s a brilliant, labyrinthine, landmark book about how Australians imagined and created their histories both human and environmental. Chapter Twelve takes readers into wilderness landscapes and reveals them to be peopled, and storied, after all. Why do conservation campaigns so often deny the intimate relationships between humans and the non-human world? Tom’s phrase ‘bleeding sepia into green’ has stayed with me.

Michael Adams

In Eva Hornung’s Dog Boy (2009), the wild child story pivots around questions of what it means to accept and be accepted by strange others. It navigates the collapse of human care and being, and its replacement by a different, more-than-human, culture and ecology of care and identity, deep in the heart of a heartless city. Dog Boy is an inspirational compass for relocating ourselves in a world of social and environmental unknown unknowns.

Rebe Taylor

Patsy Cameron’s Grease and Ochre: The blending of two cultures at the colonial sea frontier (2011) changed how I saw the Bass Strait islands and how I wrote my last book. Her work taught me that the islands were not just a place where her Tasmanian Aboriginal ancestors ‘survived’ due to the early nineteenth-century sealing trade. The environment’s ‘remoteness and wild beauty’, its seasons and resources, shaped the coming together of European and Aboriginal cultures to create a ‘new lifeworld and a new people’.

Tony Hughes-d’Aeth

Barbara York Main’s Between Wodjil and Tor (1967) is a natural history of a small section of remnant bushland in the Western Australian wheatbelt. An eminent zoologist, known for her ground-breaking work on trapdoor spiders, York Main is also a gifted prose stylist possibly the one who comes closest in Australia to the belletristic tradition of American nature writing (Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, Barry Lopez, Annie Dillard).

Barbara York Main’s Between Wodjil and Tor (1967) is a natural history of a small section of remnant bushland in the Western Australian wheatbelt. An eminent zoologist, known for her ground-breaking work on trapdoor spiders, York Main is also a gifted prose stylist possibly the one who comes closest in Australia to the belletristic tradition of American nature writing (Henry David Thoreau, Aldo Leopold, Barry Lopez, Annie Dillard).

Sarah Holland-Batt

‘Somehow it seems sufficient,’ A.R. Ammons once wrote, ‘to see and hear whatever coming and going is losing the self to the victory of stones and trees.’ I think of those lines when I read Judith Beveridge’s inimitable poetry. Beveridge shows us that finding a precise, unflinching language for the natural world and the human place within it can be a profound, reverential, and philosophical act. I especially love her pelagic volume Storm and Honey (2009).

Sophie Cunningham

When I first read Stephen Muecke, Paddy Roe, and Krim Benterrak’s Reading the Country: Introduction to nomadology in 1984, the year of publication, it was a revelation, introducing me to the idea that landscape could speak. What you had to do was learn to listen to it.

When I first read Stephen Muecke, Paddy Roe, and Krim Benterrak’s Reading the Country: Introduction to nomadology in 1984, the year of publication, it was a revelation, introducing me to the idea that landscape could speak. What you had to do was learn to listen to it.

John Kinsella

When my brother, an intense naturalist from the age of six, received Vincent Serventy’s book Dryandra: The story of an Australian forest (1970) for his birthday, I couldn’t wait to read it. It made an impression on me, and its passion for place and the natural world stayed with me. In my late twenties, for three years, I lived on and off next to Dryandra Forest with my brother. His knowledge of the forest was broad. We often walked through its south-eastern outskirts, talking of the Serventy book. I couldn’t engage with the many birds, echidnas, kangaroos, and even numbats without being aware of the book’s knowledge. The book that stopped a bauxite mine activist environmental literature at its best!

Tom Griffiths

I read Eric Rolls’s A Million Wild Acres (1981) soon after I returned from my first trip to Europe. It seemed to encapsulate all that is wonderful, earthy, feral, and unruly about my country. Animals, plants, and insects share the stage with humans in this democratic, ecological, cross-cultural saga of life in the Pilliga forest of northern New South Wales. Rolls was a farmer, poet, fisherman, and historian with a lust for life and a deep sense of wonder about the land he farmed. He enchants the landscape and its creatures with exact, spellbinding stories. It is nature writing with a distinctive, compelling Australian accent.

I read Eric Rolls’s A Million Wild Acres (1981) soon after I returned from my first trip to Europe. It seemed to encapsulate all that is wonderful, earthy, feral, and unruly about my country. Animals, plants, and insects share the stage with humans in this democratic, ecological, cross-cultural saga of life in the Pilliga forest of northern New South Wales. Rolls was a farmer, poet, fisherman, and historian with a lust for life and a deep sense of wonder about the land he farmed. He enchants the landscape and its creatures with exact, spellbinding stories. It is nature writing with a distinctive, compelling Australian accent.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.