See You at the Toxteth: The best of Cliff Hardy and Corris on crime

Allen & Unwin, $29.99 pb, 334 pp, 9781760875633

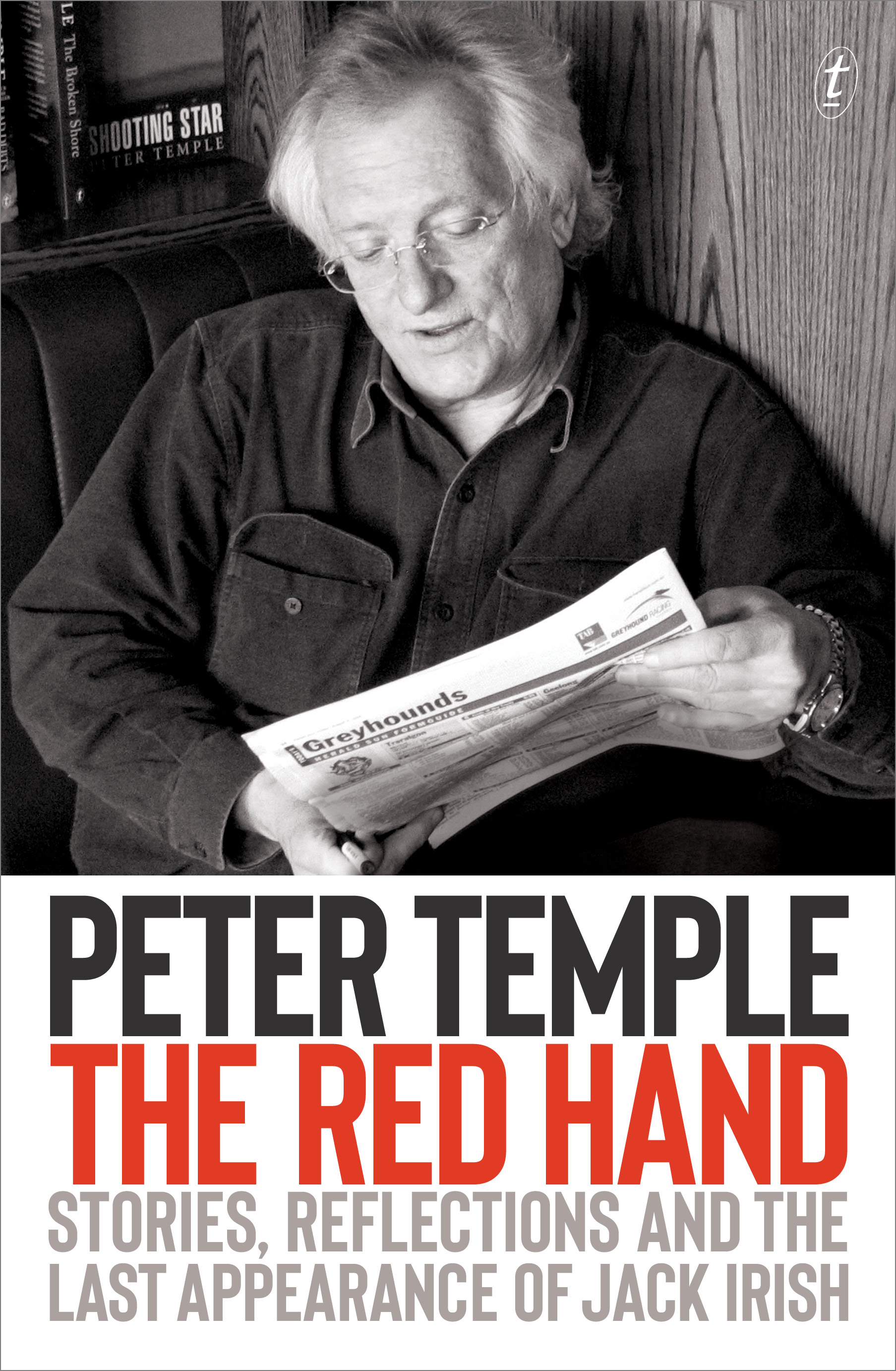

The Red Hand: Stories, reflections and the last appearance of Jack Irish

Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 387 pp, 9781922268273

See You at the Toxteth by Peter Corris, selected by Jean Bedford & The Red Hand by Peter Temple

Two of the greatest Australian crime writers died within six months of each other in 2018. Peter Temple authored nine novels, four of which featured roustabout Melbourne private detective Jack Irish, and one of which, Truth, won the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2010. Temple died on 8 March 2018, aged seventy-one. Peter Corris was more prolific, writing a staggering eighty-eight books across his career, including historical fiction, biography, sport, and Pacific history. Forty-two of those highlighted the travails of punchy Sydney P.I. Cliff Hardy. Corris died on 30 August 2018, seventy-six and virtually blind.

That their respective publishers have issued nearly simultaneous compendiums that contain previously unpublished fiction, reviews, essays, and columns seems a fitting tribute to the contributions both men made to their houses. It is also a boon for readers. Fans will lap up Corris’s ‘An ABC of Crime Writing’ manual and Temple’s 100-page unfinished Jack Irish novel. Those unfamiliar with the work of either author are provided with enjoyable springboards into their messy, hardboiled, accomplished worlds.

Let’s start with Corris. What a writer he was. In the introduction, his widow, Jean Bedford, claims that Corris rarely plotted his stories: they simply flowed. Dip into any of the twelve Cliff Hardy short stories that follow and you will find this hard to believe. The first, ‘Man’s Best Friend’ was written in 1984, while the last, ‘Break Point’ appeared in 2007. The consistency of tone is remarkable, as is the sense of a man ageing yet keeping up with the changing times. Mobile phones and the internet appear as the detective’s craft evolves, while Hardy learns to employ his experienced brain rather than resort to fisticuffs in problem solving.

His late-in-life columns for the Newtown Review of Books, some of which are collected here, candidly reveal the author’s disappointments. Lee Child’s later work and the fact none of Corris’s stories ever made it to the screen are notable bugbears.Collections of short stories can often be jarring, as the reader reinvests in new scenarios and characters every twenty pages, but this pitfall is avoided here. The effect is akin to following a detective over the course of a few months’ worth of cases, even though decades have passed. Corris never flagged in his enthusiasm for Hardy’s melancholic life of small-time corruption and local hoodlums, of Glebe’s descent into gentrification. Ironically, the early stories are reminiscent of Mickey Spillane’s violent Mike Hammer series, which Corris later professes to dislike, saying they have a, ‘mindless, fascist character’. Once the guns and knockout punches are set aside, Corris moves more towards Dashiell Hammett, a register he satisfyingly settled on throughout the Hardy novels.

Peter Corris (photograph via Penguin)

Peter Corris (photograph via Penguin)

Corris mentions our other featured author in passing, under ‘G is for gambling’ in his A-Z. ‘Gambling has not featured much … in crime fiction, though it crops up in Dick Francis’s racing novels (see H for horses), and Peter Temple’s character Jack Irish (Bad Debts, 1996, and following) is a punter and variously involved in the world of racing.’

Indeed, he is. The cover photograph of The Red Hand shows Temple scrutinising the form guide. Inside, we are presented with a number of also-rans, including Temple’s screenplay for Valentine’s Day, a football comedy that was screened on the ABC in 2008. That, and many of his ‘reflections, reviews and essays’, are arguably of limited interest and only for completists, although he does deliver a refreshing brand of dismissive sarcasm in excoriations of John le Carré and Kathy Reichs. ‘Absolute Friends joins the list of recent le Carré novels that resemble Zeppelins: huge things that take forever to inflate, float around for a bit, then expire in flames.’ Then, on Reichs’s Grave Secrets: ‘And it is a fact that many writers peak early and then trundle downhill with the sound this book makes: the hollow noise of empty garbage bins being dragged back to base.’

Only six short stories are offered, with length seeming to equate to strength. ‘Missing Cuffney’ (2003) and ‘Cedric Abroad’ (2010), at twenty-two and forty pages respectively, permit Temple to flesh out scenarios and characters. It may sound counterintuitive given his preponderance for quickfire banter, but I always found his long-form work less indulgent. The world of his novels seems vast and densely populated. Every character is armed with a loaded retort. If at first he felt like an Australian Elmore Leonard, as his career progressed, he broke free of convention and became something all his own.

Lovers of Jack Irish will be thrilled and devastated to read 20,000 words of what publisher Michael Heyward dubs High Art. If the title is meant to be a nod to the crime writer who conquered the literary world, its significance is apt. The book, or what there is of it, is dazzling. Irish’s plethora of new simultaneous cases is instantly engaging, short-circuiting the brain as we scrabble to work out how they are all connected – a hobbled racehorse, the disappearance of an art assessor, a restaurant shake-down, and, through it all, the enigmatic Jack Irish, barely holding it together. It ends just when you’re completely hooked and the realisation hits: Peter Temple is gone; we will never know the answers.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.