Consolation

Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 394 pp

Disher country

There are at least two types of ‘snowdroppers’ in the world. I grew up around economic snowdroppers, working-class women who stole laundry from clothing lines in more affluent suburbs and sold the contraband, mostly linen and women’s clothing, to pawnshops across inner Melbourne. The snowdropper introduced early in Garry Disher’s new crime novel, Consolation, is of another variety. He steals underwear, women’s underwear specifically, then trophies the garments home and enjoys their company. The thief is pursued by Constable Paul Hirschhausen, the local cop in the town of Tiverton, whom we know from Disher’s previous novels in this series, Bitter Wash Road (2013) and Peace (2019).

In addition to the mystery of the missing undergarments, a more disturbing scene confronts the reader early in the story. ‘Hirsch’, as the copper is affectionately known, discovers a child who has been held captive in a caravan parked in the driveway of a family home. She has been kept in a destitute state and watched over by a CCTV camera to ensure that she cannot escape. The child is taken into protection, and both the policeman and reader are forced to speculate on the origins of such cruelty and what may have occurred inside the caravan.

These plot threads not only hold our attention but accelerate the pulse rate, initially suggesting a hint of a depraved sexual nature. But Disher, as he has masterfully done in his previous works of fiction (this is his thirty-ninth), entwines Consolation with additional narrative threads. Some are eventually woven together, while others remain determinedly loose. Neither of these elements becomes the central focus of the novel, and yet they inform the darkening portrait of yet another rural gothic tale.

Through Hirsch we are introduced to small-town life in Australia. Disher again leaves behind the badlands and backblocks of Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula (the setting of several of his previous works) for regional South Australia. Hirsch investigates crimes from the absolutely petty to gruesome murder. He often visits the lonely and elderly. He walks the streets of the town to reassure the locals of a police presence, while dodging a persistent stalker, who may either want to date the policeman or do him harm. Or is it both?

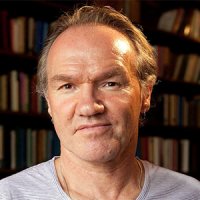

Garry Disher (Darren James/Text Publishing)

Garry Disher (Darren James/Text Publishing)

Disher’s crime novels, as with other fine books in the genre, are about much more than criminality. He is a writer with an acute sociological sensibility. The ensemble cast of Tiverton and the surrounding countryside represent a microcosm of rural life. Some people in the town are loving. Others are funny, dry, or eccentric. As a member of the community, Hirsch is expected not only to hunt down criminals but also to work on his singing voice for a local performance. As a result, while the plot never stalls, it isn’t driven at the breakneck speed of some crime fictions. Consequently, the story is better served.

What drives Consolation is greed. Certain people in Tiverton stand to benefit financially from the demise of others. Property and land are at the heart of this avarice, an economic staple underpinning the viability of families and communities amongst settler-Australians. There is both a sniff of old money and the realities of the marginal existence endured by those who have little money and no place else to go. The fragility of rural life can unify communities, but as Disher highlights, it can drive seemingly ordinary citizens to contemplate darker possibilities. We are never sure whom we can trust in this novel, and we remain wary of apparent truth.

Disher is a great landscape writer. We taste the dust, listen to the rain, and smell the same air as his characters. Being a fiction writer with an appreciation of Disher’s long career, I have often thought about his process of writing place. He must have driven along the same lonely roads that Constable Hirschhausen does. This produces an atmosphere of real authenticity. The fictional town of Tiverton surely exists somewhere, along with its occasionally menacing characters.

Debates surrounding the relative value of literary and genre fiction have been around for a long time. When the crime writer Peter Temple won the Miles Franklin Literary Award in 2010 for his book Truth, some people were surprised. Others were relieved that the division between the genres had broken down. This was not strictly so, of course. Good crime fiction delivers gripping plot and character. Australian crime fiction is in a healthy state at the moment. In recent years, writers such as Jane Harper and Chris Hammer have enjoyed remarkable and deserved success. They write great books and they sell well.

Garry Disher is something of an elder of the genre in Australia these days. (He has also enjoyed international success.) He has consistently hit the mark with books that satisfy crime readers while producing all the qualities expected of a literary novel. Disher is one of this country’s finest writers, as Consolation attests.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.