Britain’s atomic oval

Australia became the oval on which Britain’s nuclear game was to be played.

Report of the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia

When I was launching my book Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga story in 2016, one of the guests put it to me that the name Maralinga should be just as recognisable in Australian society as Gallipoli. This comment suggested that the British tests had a broader meaning that spoke to a national mythology and were not just interesting historical events.

I have pondered this comment many times since, especially while writing my most recent book, The Secret of Emu Field: Britain’s forgotten atomic tests in Australia. Both of these books provide insights into the national character not of just Britain but of Australia as well, just as the Gallipoli story does. The stories of the atomic tests do not necessarily make for rousing patriotic reading, but instead pose serious questions about how Australia saw itself then in relation to its former colonial master, and about whether echoes of that self-image persist to this day.

Gallipoli remains a foundational myth for this nation, albeit more complicated now, but still embedded deeply in national folklore. At the very least, Gallipoli is recognisable as a place of national importance, wreathed in a comfortably opaque fog of reverence. Maralinga does not have anything like the name recognition or the cultural resonance, and Emu Field and Monte Bello have effectively none at all. Yet at Monte Bello Islands (Western Australia), Maralinga and Emu Field (South Australia), between 1952 and 1963, Australia itself was put to the test, along with the twelve full-scale atomic weapons and hundreds of associated toxic experiments.

One way to understand the British tests is through the concept of nuclear colonialism. This powerful explanatory term captures a global geopolitical hierarchy in which the nuclear-armed countries have, from the beginning, transferred the risks of atomic testing onto countries and populations lower down the pecking order, generally to colonies or former colonies, or to their own indigenous peoples.

The term nuclear colonialism was coined in the early 1990s by the US anti–nuclear weapons testing activist Jennifer Viereck. This species of colonialism is defined as ‘the taking (or destruction) of other peoples’ natural resources, lands, and wellbeing for one’s own, in the furtherance of nuclear development’ (‘Nuclear colonialism’, Healing Ourselves and Mother Earth).

The concept of nuclear colonialism makes at least some of what Britain did during its test series in Australia comprehensible. Australia, as a sovereign nation, indeed had agency in its decision making around the tests, but the fact that it did not exercise it effectively points to the weight of colonial history bearing down upon the individual decision makers. For Britain’s part, the casual way it placed an obligation on Australia and later walked away without a backward glance at the aftermath (until forced to do so by the Royal Commission created by the Hawke government) indicates an imperial aloofness and sense of entitlement in its dealings with Australia.

In The Secret of Emu Field, I mention the ‘peculiar bonds of colonialism’. What I meant was the distorting effect a history of imperial conquest has on former colonies’ relationships with their colonisers, leading sometimes to servility. This was the case in relation to the atomic weapons tests in Australia that saw the federal government ask few questions about the risks of the tests and contribute more to their cost than Britain had even asked for. The Australian government seemed both pleased to be asked and overly eager to volunteer resources that hadn’t been requested. In a personal letter to his British counterpart in November 1953, Prime Minister Robert Menzies assured Winston Churchill of the ‘ancient structural unity’ that bound Australia to Britain.

That ‘structural unity’ was the backdrop for a series of unwise decisions by the Australian government. As I wrote in Atomic Thunder: ‘The truth is unpalatable but must be faced: Australia in the 1950s and early 1960s was essentially an atomic banana republic, useful only for its resources, especially uranium and land.’

Both of these commodities were of considerable interest to Britain, which wanted them with no strings attached. While uranium sales were subjected to harder bargaining by the Australian government, the land was not. Large swathes of Australian territory were handed over with few questions asked and little oversight, especially for the first two test series at Monte Bello Islands and Emu Field in the early 1950s. The two fission bomb tests known as Operation Totem at Emu Field in October 1953 did incalculable damage to the Anangu people of the Western Desert.

The Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia was a mid-1980s exercise in holding the ‘Mother Country’ to account. Menzies was not spared: ‘In taking it upon himself to embrace British interests as being synonymous with those of Australia, and to expose his country and people to the risk of radioactive contamination, Menzies was merely acting according to his well-exposed Anglophilan sentiments. It was consistent with his approach when, as Prime Minister in 1939, he announced that as Britain was at war with Germany, Australia also was automatically at war with the same enemy.’

The Royal Commission is not without its critics, some of whom point to the way it positioned Australia as a victim of Britain rather than an independent nation with decision-making powers, even if these were not well exercised. Scholar Jessica Urwin argues that, contrary to the emphases placed by the Royal Commission, ‘facilitating a nuclear program on Australian soil sought to fulfil British and Australian desires’.

The desire to do business with Britain on uranium exports and the development of Australia’s own nuclear capability were compelling motives, quietly sitting beneath the overt Anglophilia of the prime minister. While there is no doubt that the Menzies government had motivations above and beyond simple sycophancy, colonial history gave Menzies’ motives a ready-made loyalty narrative, but that loyalty seemingly made Australia incompetent when dealing with the dangerous reality of the tests.

Although Britain did consider using some parts of its own homeland for atomic testing, there was no appetite in Whitehall for domestic populations being exposed to poisonous fallout. The merest hint in the British parliament of such tests being held in Scotland or Lincolnshire was howled down. Impassioned speeches were made promising that tests of this kind would never take place in the British Isles, owing to the risks. Instead, Britain made a thorough search of its former colonies and finally settled, somewhat reluctantly, on Australia (Canada was much higher up the list). The people who would bear the brunt of these tests would not be British civilians – they would be Australian.

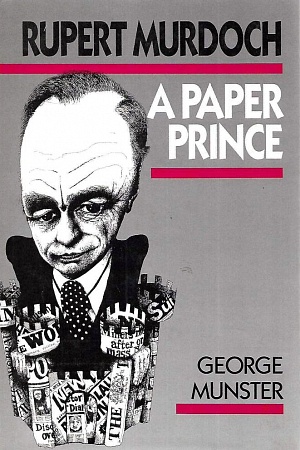

When the Australian population came to know about the first atomic bomb test, Operation Hurricane held in October 1952, the response was mostly positive. Part of the reason for the equanimity was the obedience of the Australian media, many parts of which were cheerleaders rather than investigators. The entrenched marginalisation of Aboriginal populations was also a factor in the ease with which the tests were established and conducted.

Media compliance was greatly assisted by the instigation of a system of secret D-notices in the lead-up to Operation Hurricane. While Britain had lobbied Australia for decades to establish a D-notice system, Menzies was the first Australian prime minister to acquiesce. These ‘Defence notices’ were not legislated but were instead covert agreements between the government and the media not to report on certain specified activities in the interests of ‘national security’. Flattered at being treated as national security insiders, the media owners all agreed.

President of the Royal Commission, James ‘Diamond Jim’ McClelland, described Menzies’ actions in making Australian territory available for the tests as both ‘grovelling’ and ‘insouciant’. Resources and Energy Minister Peter Walsh, suddenly finding himself responsible for the radioactive mess at the British atomic test sites when the Hawke government came to power in 1983, went further. In 1984, he described Menzies as ‘the lickspittle Empire loyalist who regarded Australia as a colonial vassal of the British crown’. This framing of the tests as an act of colonial servility still dominates in the post-Royal Commission era.

Australia itself was a non-nuclear nation, albeit one in possession of those banana republic goods sought after by a developing nuclear nation. The Australian government was excluded from managing the way tests were conducted and kept itself ignorant of the contamination left behind until years later. During the early tests, at Monte Bello and Emu Field, the Australian Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee did not exist, so Australia

did not have the veto on the firing of each test that was available from 1956 onwards.

Should Monte Bello, Emu Field, and Maralinga have a special place in Australia’s national conversation, as Gallipoli does? After all, Gallipoli is hardly a tale of triumph – it has failure and colonial hubris written all over it. Inasmuch as Gallipoli and the Australian atomic test sites are the places where Australia willingly surrendered its own best interests in a vain attempt to gain favour with its erstwhile coloniser, there are reasons to assent. Like all such endeavours, it backfired. Australia was left with a contamination problem that cost tens of millions of dollars to partially remediate, and an ongoing legacy of illness and anxiety among those who were most exposed to the toxins.

The story of the British tests portrays Australia as an immature democracy, anxious to please Britain. It was a shadowy time, with little information of substance placed before the Australian public for their informed consent. The secrecy of the atomic tests enabled experiments of considerable risk to be conducted and their aftermath to be left unaddressed for many years. These stories may have not so much Gallipoli’s mythic themes of forging a nation in the heat of battle as the rather less palatable ones of ineptness and insecurity that are the consequences of a lack of national direction. Australia did emerge, at least partially, from this post-colonial funk in the decades after the British nuclear tests to seize hold of its sovereignty, but the firmness of that grip is always an open question.

I claim in my books that in handing over part of its territory to a foreign nation for secretive and dangerous activities, Australia’s responsibilities as a sovereign nation were compromised during the eleven years of the British atomic weapons test programs. This larger meaning of the tests gives them ongoing significance as Australia continues to play a subordinate role to ‘great and powerful friends’ that have little real interest in Australia itself.

This commentary is generously supported by the Judith Neilson Institute for Journalism and Ideas.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.