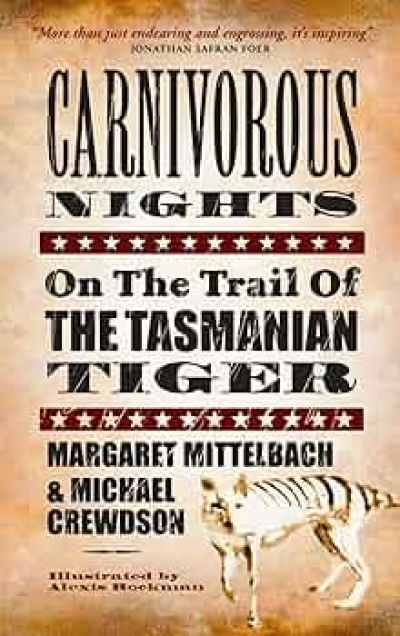

It is easy to understand two New York naturalists becoming fascinated with a thylacine. Margaret Mittelbach and Michael Crewdson discovered one, stuffed and mounted, in Manhattan’s American Museum of Natural History, and began to visit it with ‘something akin to amorous fervour’. It’s equally easy to understand how this rare specimen, with its ‘glorious Seussian stripes’ and tragically fascinating mythology, inspired the pair to travel to Tasmania to learn more about its origins. What is more difficult to understand is why, once Mittelbach and Crewdson had surveyed the existing literature on the thylacine, they pressed on to write and publish Carnivorous Nights: On the Trail of the Tasmanian Tiger instead of deciding that the story had been well and truly told. On my bookshelves are Tasmanian Tiger: A Lesson to Be Learnt by Eric Guiler and Philippe Godard (1998), and David Owen’s Thylacine (2003). Close by are two novels, Heather Rose’s White Heart (1999) and Julia Leigh’s The Hunter (1999), that pursue the tiger into fictional territory. Since these are just a fraction of the books already written on the subject, I would have thought that any new tiger book would have something significant to add to the story. Carnivorous Nights, unfortunately, does not.

...

(read more)