Peter Tyndall

Although Peter Tyndall’s art is littered with the breezy, post-pop imagery of cartoons and illustrations, there is a sparse and unrelenting quality to his work. When assembled together, as in the current retrospective at Buxton Contemporary, they threaten to blur into one. Though this is by design, every painting and print here is a fragment of a single work that has been unwavering in its consistency over the past fifty years.

Since the late 1970s, Tyndall has consistently made use of relatively limited means. Most of his works revolve around the same organising motif: an ideogram of a ‘painting’ (a square with two lines sticking out like prongs), usually arranged into an endlessly repeating diamond-like pattern. His palette is often restricted to black and yellow on white, and his paintings are all hung in a uniform fashion (suspended from the walls by two strings, mirroring his ideogram). The exhibition labels also act as extensions of the works; each artwork shares the uniform title; ‘detail/A Person Looks At A Work Of Art/ someone looks at something … LOGOS/HA HA’. While this preoccupation with the fundamentals of art (viewership, material supports, institutional infrastructures, and so on) is indebted to both conceptualism and minimalism, there is little dourness to his project. Tyndall’s contemporary, the artist and critic Robert Rooney, compared him to a television comedy writer in his ingenuity in re-writing the same joke over and over again. The strength of Tyndall’s work is in the balance he achieves between an unwavering austerity and rigour with his reflexive and subtle humour.

Where there have been survey shows in the past dedicated to Tyndall, the current retrospective, curated by Samantha Comte and Simon Maidment, is the largest to date and fills both floors of the Buxton Contemporary. The ground floor traces the development of Tyndall’s style from his early beginnings in abstraction through to the present (the earliest work is a small painting from 1972, the latest is his painting ideogram applied to the doors of the second-floor elevators). After various deployments of his ideogram across decidedly painterly works in the second half of the 1970s, he had settled on his signature approach with a degree of finality by 1980. After that it becomes difficult to determine when a painting is from, and it is only from small changes in his iconographic motifs that chronological clues are given as to when over the past forty years they were made.

The works themselves are unclear on their temporal status. Many carry two dates, often with large gaps of time between (the longest being 1974 and 1991). It isn’t clear what either date implies, the artworks usually lacking any obvious signs of amendments or additions. This timelessness is partly due to Tyndall’s abandonment of any obvious signs of painterliness. His works are decidedly ‘cool’ and non-visceral, and from a distance appear almost mechanically produced. Up close, the blocks of white and black retain visible brushwork, as do the stripes of yellow where paint pools at their edges. Yet this is of an anonymous character, and there is something of the signwriter in his paintings. Indeed, many are almost billboard-like in their size, spreading across two or three canvases. They tend to encourage, at least at first, a fairly restricted response closer to ‘reading’ in the way one might look at a newspaper cartoon or advertisement.

Upstairs is predominately focused on works from the 1990s onwards. The main upstairs room has several of his most straightforward pop-appropriation paintings, as well as several intriguing text paintings from 1991 that pursue an otherwise unexplored stylistic path. There are also several vitrines focused on his more ephemeral paper works, including a selection of Tyndall’s voluminous mail art (the archive of his correspondence with the Brisbane conceptualist painter Robert McPherson contains about 13,000 individual items). It seems that in this correspondence his messier, painterly energies were channelled as his main art practice became restrained.

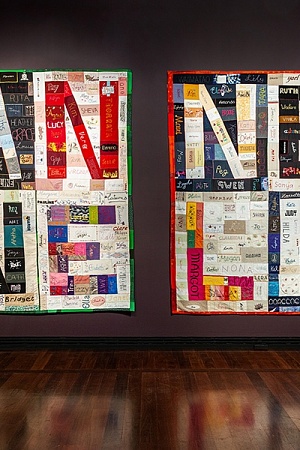

Peter Tyndall and Slave Guitars (courtesy Anna Schwartz Gallery)

Peter Tyndall and Slave Guitars (courtesy Anna Schwartz Gallery)

While the exhibition is comprehensive in regards to Tyndall’s painting work, there are some notable absences. The section of the show focused on his Slave Guitars project is a case in point. The installation itself is not especially forthcoming; in a section on the ground floor, the instruments/props/sculptures are mutely on display. That Slave Guitars was an actual musical project – a novel attempt to combine the Australian hard-boogie minimalism of ACDC and Lobby Loyde with the New York hard minimalism of Glenn Branca – would be lost on many visitors to the show. This is not only due to the absence of explanatory texts throughout the exhibition (which in itself is not a negative), but to the curatorial decision to exclude any sonic component. Given that Tyndall is an artist for whom music was as an important influence and who was actively involved in the multifaceted Melbourne art/punk crossover of the 1970s and 1980s, the absence is disappointing (I am reminded of a complaint once made to me by a former artist/gallerist now musician that ‘nobody in the art world cares about music’).

In a similar vein, Tyndall’s involvement in performance art did not make the cut. Although archival material documenting these actions may have been excluded to avoid giving a museological-cum-mausoleum quality to an exhibition that celebrates a still prodigious artist, consigning this facet exclusively to the catalogue limits a full appreciation of the more radical aspects of Tyndall’s art practice.

Given the familiarity and stability of Tyndall’s signature style, it is the earlier 1970s works that are the surprises of the exhibition. The first room of the exhibition is dominated by two large paintings from 1973 and 1974 that are of a grotty, abject sort of abstraction that feels decidedly contemporary. The stressed, worn-down, worn-out quality of these paintings – examples not so much of post-painterly abstraction as non-painterly abstraction – are similar to approaches among artists exhibiting in the smaller artist-run galleries in Melbourne of late. The 1973 Ehh (even the nonchalant title feels very now) is a span of dusty, dirty pink that is almost floor-like, the surface sparsely marked by tiny, seemingly accidental drops of paint, while larger, arbitrary areas of scrubbed-out paint resemble grease stains.

This deflated, anti-heroic approach to abstraction continues in the earliest works, which Tyndall undertook as part of his unified painting project. These early works, part of an ‘Untitled’ series numbering at least one hundred pieces, are small parodies of painting. The emergence of Tyndall’s serialism is evidenced here, each work maintaining a uniform, modest size and design (the first version of his painting ideograph). Some are direct parodies of other Australian artists; Untitled Painting No. 58 a Fred Williams Painting raining (1976) miniaturises Williams style into something like smeared mud, possibly even scatological. Much like his earlier abstracts, there is timeliness in their approach. It is only the wooden frames and large patches of unpainted, untreated brown linen that betray their age.

Although Tyndall was among both the first wave of post-minimalists and post-modernists in Australia (he was included in the controversial 1982 Popism exhibition at NGV), these earlier works also point to his emergence from an older and more local painting tradition. Tyndall was in many respects one of the last contemporary Australian artists working in a European idiom whose trajectory was via a pre-war model of independent training, having studied art part-time through the Victorian Artists Society rather than at the National Gallery School. The first half of the exhibition here has a synergy with a recent series of exhibitions held by the small Rosanna-based gallery Guzzler that have focused on the pre-modernist juvenilia of pioneering Australian conceptualist Ian Burn. Given the post-national character of post-1960s art in Australia, it can be easy to forget the more immediate and unfashionable local contexts from which this then-contemporary art was also in dialogue.

Artwork Peter Tyndall (photograph by Christian Capurro)

Artwork Peter Tyndall (photograph by Christian Capurro)

There is also prescience in Tyndall’s repeated grid (what he refers to as a ‘matrix’). Although it appears at first simply a pastiche on minimalism and geometric abstraction, an appropriation of both Sol LeWitt and Piet Mondrian, it is the organising principle of Tyndall’s philosophy of art. While at one level this is a device that links each of his individual works into one single overarching work, there is also the implication that Tyndall’s work itself forms part of a wider grouping of all paintings (and images). No artwork is in itself isolated, not only within a wider scheme of art history (whether socially or formally related), but on the individual level. Each viewer brings to an artwork the sum total of all other artworks they have seen. Even the artworks are conceived as extensions of the audience with the medium for each work listed as ‘A Person Looks At A Work of Art/ someone looks at something … / CULTURAL CONSUMPTION PRODUCT’ rather than oil, acrylic, canvas, paper, etc. Here, Tyndall’s grid becomes something of an analog for our present network society. Tyndall’s painting ideograph is not unlike a diode, and his ever-repeating matrix itself starts to appear like a never-ending circuit board. Although Tyndall’s ongoing online blog-work bLOGOS/HA HA has not been integrated into the exhibition, the wall of works from 2018 on the second floor has something of the logic of internet content. There are more than one hundred individual works, painted quickly onto sheets of unstretched canvas (the dating suggests that he was doing one painting one a day). Recalling the pithy and transient nature of online posting, these works form a scattered collection of cryptograms, fake band posters, art puns, poems, and cartoons that share the ephemeral quality of memes, user comments, and blogposts.

It could be that Tyndall views his matrix as a fishing net. There are several nods to fishing throughout the exhibition. A highlight of the show is a 1984/2008 painting that depicts the torso of a fisherman. The woodcut-like design has been overloaded with dizzying textures, while the twisting fish is overlayed with Tyndall’s yellow painting matrix. It seems possible that the hanging wires on every painting are fishing wire, and that, as in a scene in a cartoon, the audience and artist are two fishers who have both hooked onto the same old boot thinking they have caught a fish.

Peter Tyndall is at Buxton Contemporary until 16 April 2023.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.