A Wilde Ballet

.jpg)

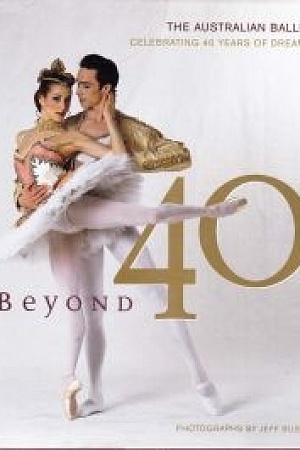

As a former dancer who has grappled with questions about sexuality, I was often struck by ballet’s contradictory relationship with queer inclusion and representation. On one hand, the art form – especially in Western countries – has long been seen as a safe space for the LGBTQ+ community. Ballet legends like Rudolf Nureyev, John Neumeier, and Jack Soto lived openly as gay men, and in 1997 an American study estimated that more than half of professional male dancers identified as gay or bisexual. Yet despite the sector’s inclusivity, the art form has also played a role in suppressing queer representation onstage.

Much of the classical repertoire performed by ballet companies is rooted in nineteenth-century narratives that perpetuate heteronormative ideas of gender and sexuality. While modern companies and contemporary works have begun to challenge these conventions – for example Matthew Bourne’s 1995 reimagining of Swan Lake, which replaced the traditional corps de ballet with bare-chested male swans – portrayals of queer love remain largely absent from the programming of leading ballet companies.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.