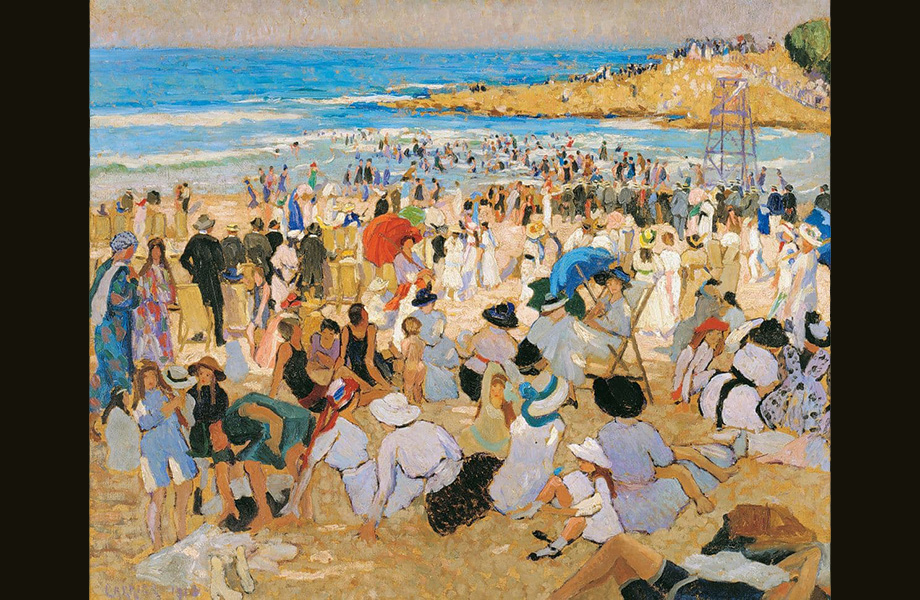

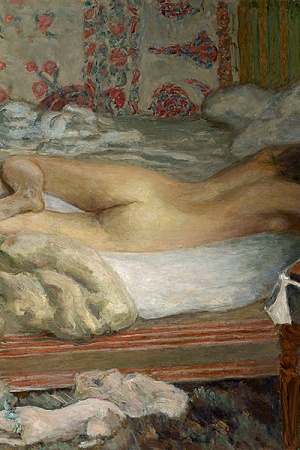

Ethel Carrick and Anne Dangar

These paired exhibitions do great credit to the National Gallery of Australia’s program promoting the fortunes of women artists in Australia: Know My Name. After the initial selective survey show that included 150 artists, the Gallery is ‘drilling down’ to heavily researched presentations of historical figures. In this case, two women born in the late nineteenth century: Ethel Carrick (1872-1952) and Anne Dangar (1885-1951). Neither were ‘dinkum Aussies’: the oil painter Carrick was born into a prosperous business family in Middlesex and first associated with this country through her husband of ten years, Melbourne portraitist Emanuel Phillips Fox. Dangar, an expatriate from Kempsey, spent the bulk of her professional life as a painter and avant-garde potter in regional France. The two are surely exponents of ‘un-Australian art’ (to use the witty rubric of Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson to defuse stultifying questions of national identity).

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.