The Invisible Woman by Ralph Fiennes

Orson Welles once described himself as a ‘king’ actor. Ralph Fiennes seems born to play dukes: nearly all his screen characters, even the crooks and madmen, share an imperious quality that goes with a kind of stony reticence. It felt natural that he should make his film directorial début with an adaptation of Coriolanus (2011), one of Shakespeare’s most misanthropic tragedies, in which he played the lead role of a Roman general with a frank contempt for the mob.

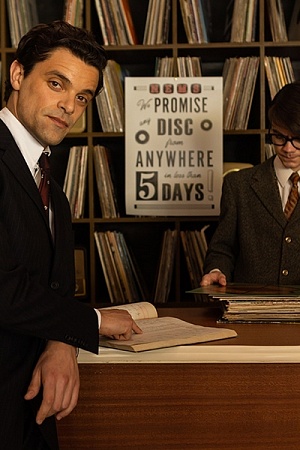

His follow-up, The Invisible Woman, scripted by Abi Morgan from a biography by Claire Tomalin (1990), initially seems an exception to the rule: Fiennes has cast himself as Charles Dickens, a writer who has never been accused of lacking the common touch. But this is not quite the received notion of Dickens, the robustly extroverted Victorian patriarch: from the outset there is a hint of impatience, even neurosis, in Fiennes’s preoccupied stare.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.