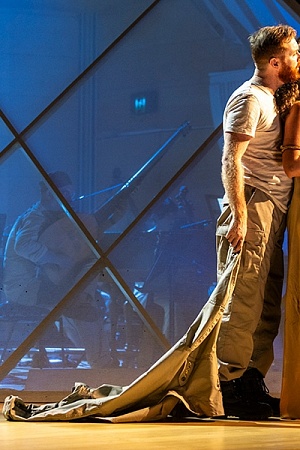

Parsifal (Opera Australia) ★★★★★

Of all Richard Wagner’s operatic works, it is Parsifal that divides audiences most. As with the Ring, its ambiguity lends itself to multiple interpretations. The music has been praised and admired by the greatest of critics and musicians, including those who heard it when it was new: Mahler, Sibelius, Berg, Debussy, George Bernard Shaw. It is the text, drama, and characters, the overblown religiosity, ritual, the piousness and passivity of the hero and his denial of sex and sexuality that cause the problems. Indeed, the only character Debussy found sympathetic was Klingsor, the evil one in the piece who has castrated himself in order to achieve power by his immunity to sexual desire. Whatever Debussy thought of the text, however, the music captivated him, and musical references to Parsifal appear in Pelléas et Mélisande, which he composed after hearing the work of the Bayreuth master.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (2)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.