Whiteley (Opera Australia) ★★★★

Unlike the many films about the lives of artists, operas in which visual artists feature are few, though two of the most popular in the repertoire, Puccini’s Tosca and La Bohème, both have painters as central characters. The lives of artists are often messy affairs and resist convenient shaping into narrative arcs, with the actual creative process difficult to dramatise effectively. The new film Never Look Away, by Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck, controversially, though loosely based on the life of German artist Gerhard Richter, achieves a remarkable degree of success in showing the development of a creative artist, often actually at work on a series of paintings, while a panoramic sequence of events play out in the background. It is one of the few films that offer a plausible insight into the creative process.

The challenge for librettist Justin Fleming and composer Elena Kats-Chernin was to find a way into the jumbled events of both Brett and Wendy Whiteley’s rackety lives. Brett’s life is well documented, with several major biographies, including an excellent and exhaustive recent one by Ashleigh Wilson, who acted as consultant on the preparation of the opera. There is also much documentary material, including a theatre work premièred in 2019. Brett Whiteley achieved what must be regarded as rockstar status in his own lifetime. A certain mythology has developed about his early exposure to the work of Vincent van Gogh, but there seems little doubt that the Dutch painter had a profound influence on Whiteley’s artistic vision and sense of self; he saw in Van Gogh the epitome of the artist as outsider.

Bradley Cooper as Frank Lloyd and Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Bradley Cooper as Frank Lloyd and Leigh Melrose as Brett Whiteley in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Opera is an exaggerative, mythologising art form, not really effective as documentary, but able through its intermediality to isolate emotional and psychological essences. One thing that emerges is Brett’s bond with Wendy, regardless of all the vicissitudes of their relationship. Opera, of course, does obsession well; W.H. Auden observed that the quality common to all great operatic roles – such as Don Giovanni, Norma, Lucia, Tristan, Isolde, Brünnhilde – is that each of them is in a ‘passionate and wilful state of being. In real life they would all be bores, even Don Giovanni.’ These are all obsessive, destructive characters. Whiteley, as operatic character, might well be appended to this list. Donald Friend perceptively observed of Whiteley: ‘His paintings are like wonderful glimpses of the world seen through holes in the death-wish.’

In the end, Whiteley has to stand on its own as a unified work of art. Can it work as a theatre piece for someone who has little or no prior knowledge of the very particular place that Whiteley occupies in the Australian psyche? Librettist Fleming has isolated three major aspects of the life around which to structure his libretto: the early precociousness; the growing addiction; and the bond between the Whiteleys. The opera follows a chronological course, commencing with Brett’s childhood and culminating in his death in 1992 and Wendy’s creation of the Secret Garden at Lavender Bay on Sydney Harbour. One had the feeling that this dramaturgical structure sometimes placed a straitjacket on a deeper exploration of character, conflict, and emotion. Several scenes felt prematurely truncated by a need to move on to the next event in the life, almost in documentary fashion, with characters often rather obviously announcing the next scene.

It is the music that allows the work to soar. Kats-Chernin’s music is impossible to categorise; her oeuvre ranges across genres, including much concert and film music as well a number of operas. Her musical idiom doesn’t fit neatly into any particular aesthetic, and is tailored with a chameleon-like facility to each current project. The music in Whiteley is vividly varied in colour, rhythm, and articulation, from a muted saxophone opening to blazing colours in the many large-scale choral and solo scenes, culminating in a muted Rosenkavalier-like ending for three female voices.

One of the most arresting scenes in the opera deals with Whiteley’s series of paintings from 1965 that arose from his fascination with the Christie murders in London in the 1940s and early 1950s. Confronting these macabre events was part of an artistic process for Whiteley that signalled a development of the acclaimed youthfully prodigious and flamboyant talent into an artistic maturity and seriousness through this engagement with good and evil.

John Christie hid some of his victims in the walls of his home (the infamous 10 Rillington Place, Notting Hill), and there is a Chorus of Women’s Ghosts that emerges from the darkness of the stage. Whiteley acknowledged: ‘I wanted to try and define evil, to put my finger on some point of evil and say that’s it. I wanted to take something as bad as the human condition could get … something filthy, repugnant, at the very bottom of the scale … and try to purge it.’ These paintings came immediately after Whiteley’s bathroom images; the contrast between the rounded, voluptuous nude forms of the former with the decaying bodies of the murder victims is striking, coloured in the opera by a dramatically dark and brooding soundscape.

Opera Australia’s utilisation of digital technology bears fruit where many of the most striking Whiteley paintings emerge on stage at various points in the narrative, all selected with skill and appropriateness. A New York scene has Whiteley’s huge series ‘The American Dream’ used to considerable visual effect, accompanied by Gershwin-like bluesy music of rhythmic drive and colour. The use of the LED screens was not overdone, and the final scene of Brett’s death, all colour drained and framed by sheer white panels, was visually stunning and poignant.

Julie Lea Goodwin as Wendy Whiteley in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

Julie Lea Goodwin as Wendy Whiteley in Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

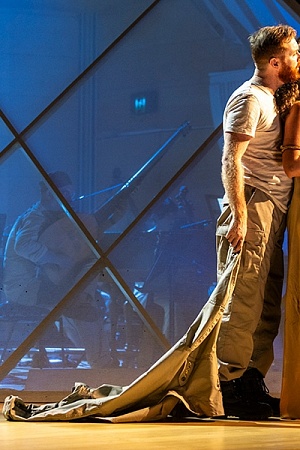

This was very much an ensemble performance led by the Brett of Leigh Melrose and Julie Lea Goodwin’s Wendy. They are both charismatic performers, visually and vocally alluring. Melrose, who is on stage virtually the whole time, has a baritone of power, richness, and nuance. His frequently deliberately exaggerated vocal articulation effectively conveys the obsessiveness of the character, which contrasts with the purity and beauty of Goodwin’s lush soprano. A sympathetic foil for Melrose’s rapidly changing emotional states, she has a number of brief character-revealing arias which display some of Kats-Chernin’s most lyrical and affecting vocal writing. This was most impressive in the poignant death scene of their friend Joel Elenberg in Bali.

Appealing performances came from Natasha Green and Kate Amos as the Whiteleys’ daughter, Arkie, at different stages in her life. Beryl, Brett’s mother, was given strong and authoritative voice and presence by Dominica Matthews, and a host of other figures move in and out of the action. The relationships were clearly dramatised with vivid characterisations by Richard Anderson, Nicholas Jones, Gregory Brown, Annabelle Chaffey, Alexander Hargreaves, Tomas Dalton, Jonathan Alley, Brad Cooper, Leah Thomas, Ruth Strutt, Celeste Lazarenko, Sitiveni Talei, and Angela Hogan, as figures such as Robert Hughes, Patrick White and even the Queen, among others, weave through the action. This is as much a chorus opera as many of the great works in the canon, and the Opera Australia Chorus – one of the glories of the company and prepared by Anthony Hunt – provides many of the most arresting moments both aurally and visually through the series of characters they create.

The cast of Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

The cast of Opera Australia's 2019 production of Whiteley at the Sydney Opera House (photograph by Prudence Upton)

The musical direction was in the capable hands of Tahu Matheson, who led the large solo, choral and orchestral forces with style and nuance. Director David Freeman used the revolving stage to good effect with spaces fluidly merging as scenes changed. Production designs by Dan Potra vividly conveyed a wide range of locations and time periods, complemented by lighting by John Rayment and digital content by Sean Nieuwenhuis, all contributing magnificently to this visual feast.

Because opera is such an expensive and labour-intensive art form, chamber opera is rapidly becoming the norm for new works, so it is exciting and heartening to experience a large-scale new opera utilising substantial solo, choral, and orchestral forces, and to realise the creative possibilities still inherent in the genre. For Opera Australia, Whiteley follows Brett Dean’s Bliss (2010), and demonstrates opera’s overwhelming power to tell significant Australian stories. One hopes that Whiteley will become part of the repertoire and that it presages other new works of similar scale and ambition.

Whiteley continues at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House, until 30 July 2019. Performance attended: July 15.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.