Cock, Cock … Who’s There?

In 2000, Mary Beard, the English scholar and classicist, published an autobiographical essay entitled ‘On Rape’ in the London Review of Books. It blazes, not in intensity of tone, but as writing that refuses to tame itself to one palatable or containable narrative. The essay allows for a space wherein questions are asked and there aren’t always answers, at least not ones that make us complacent. Beard professes to not being ‘particularly traumatised by what happened’ to her younger self, admitting that this might be a result of the experience itself having morphed into different iterations as she retold it to both herself and others. These tellings subsequently become ‘interpretations of what went on, which coexist ̶ and compete ̶ with the account’ that she writes in the opening of the piece.

In case the reader is led to think that Beard is trivialising the experience of rape, she goes on to address ‘the crucial importance, both culturally and personally of rape-narratives. For rape is always a (contested) story, as well as an event; and it is in the telling of rape-as-story, in its different versions, its shifting nuances, that cultures have always debated most intensely some of the unfathomable conflicts of sexual relations and sexual identity.’

Samira Elagoz understands the contested qualities of the rape narrative. She understands this as someone who has experienced rape twice. The first time she tells us, she is alone on stage, a chair her single prop. She is a young everywoman, slight, with ripped jeans, someone who, walking down the street, the viewer might imagine, would not attract much attention. (This is not conveying the meaning you think it might, but its relevance to this work is significant.) This calmly spoken version of Elagoz confesses, ‘It’s exactly six years since my dumb boyfriend forced himself on me.’ Horror is communicated in an envelope of banality, ushering us into a work that investigates the repercussions of rape and explores an alternative to the position of victim; a woman with agency, even if the avenues she uses to gain it are sometimes profoundly troubling.

It’s important to note that before Elagoz walks onto the stage, two things have already been revealed on the large screen backdrop. The first is white text on a black screen. It begins like a fairy tale, but quickly the story becomes monstrous with its application of pornographic language: a reference to a ‘Violence Suck-O-Matic’, and to women’s ‘cunts’ painted white as if they were cave paintings. Lasting only a few minutes, it sets a tone of unease and violence. We next watch a film that erupts psychedelically, a mélange of camp, disco, and porn. Shapes appear from bodies. There is a vulvic image that feels reminiscent of a Mapplethorpe phallic flower, somehow awash in a strange kind of beauty. Hair morphs into pubic hair that morphs into something else. A voice resplendent with camp sings ‘You Don’t Own Me’. Its lyrics of ‘I’m free and I love to be free’ resonate in the theatre.

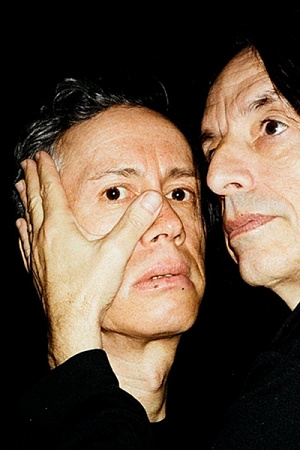

Samira Elagoz in Cock Cock ... Who's There? (photograph by Adam Forte)

Samira Elagoz in Cock Cock ... Who's There? (photograph by Adam Forte)

Elagoz is a performance artist and writer who sets out to produce a work that is intensely destabilising. As her story unfolds, the mechanism of disruption and eruption is employed continuously, except when she is onstage speaking. Later, a screeching sound reaches a painful dissonance, as if to make sure that we are not getting too comfortable. As the title denotes with its allusion to a ‘Knock, Knock’ joke, Elagoz uses an audacious kind of humour along the way. Read Rebecca Solnit’s essay, ‘The Short Happy Recent History of the Rape Joke’ in The Mother of All Questions (2017) if you don’t believe this is possible given the work’s subject matter. One of the short films gives ‘puppetry of the penis’ a different spin.

The Elagoz on stage is intensely familiar with the visual image, and so these exercises are transmitted by screen. We are told that from the age of fifteen her younger self experiences being sexualised by men and constructs a facial ‘twitch’, half-pout, half-sneer. The flood of images, of selfies, that follows is increasingly sexualised. In all of them she sports a rendition of this expression, sometimes in various states of undress. The experiments are threefold. On the website Craigslist, she posts a call for meetings with men in their apartments. The resultant footage is deeply disturbing. Elagoz’s camera captures these, for the most part, much older men from various different countries. Several speak of sexual depravity. Some of them set out to impress her with their ‘skills’, as she terms it; bizarrely and humorously, these include fire spinning. In a moment of lightness an aged, bare-chested, Iggy Pop-like rocker laughs at himself. Some of the men are rendered uncomfortable in the view of the camera, an interesting subversion of the male gaze.

But there are not many moments of reprieve. Sometimes Cock, Cock … Who’s There? feels unrelentingly brutal because of its voyeuristic impulse. Elagoz refers to herself as both ‘scientist and test rat’. She is not the first artist to produce an artistic response to her own rape. Elagoz’s work is closer to British artist Tracey Emin’s confessional work than Renaissance painter Artemisia Gentileschi’s forms of visual testimony. But the performance artist does verbally articulate the revenge fantasy of killing her rapist, as Gentileschi did when she painted herself as Judith beheading her rapist Agostino Tassi, recast as Holofernes. The fantasy is voiced by Elagoz after the second time she is raped, this time by a friend in Japan.

There are other kind of hauntings that occur but are never revealed. Elagoz’s Egyptian father, who does not seem to live with her mother, recites Arabic poetry amid the chaos of a hoarder’s domestic interior. The scale of the detritus feels like a violence, a spewing forth of repressed desire that mirrors the spewing forth of other things in the show.‘I never told my father,’ we are told.

Elagoz now travels around the world, but she returns to her hometown in Finland to interview childhood friends about their responses to her rape. Most do not know what to say. In one frame she appears with her mother and grandmother, a singular moment of opening herself up to the compassion of others.

There is an impulse to locate the authentic Samira as the one who appears without makeup or artifice alongside her mother and grandmother and her childhood friend Otto. But to do so would be erroneous. It would be making the fallacious judgement that selves performed in the digital world are inherently inauthentic. For Samira and others of her age or younger ̶ she was born in 1989 and camera phones started to be popular in her teens ̶ the selfie as a performed self is a way of being in the world. Elagoz would probably argue that hers, charged as they are with eroticism, are a revelation of desire, of a sexualised self. This Samira, either viewed as a still image of smouldering carnality, or the moving, active subject of her own explicit films, is another version of herself but no less authentic.

The day after witnessing this play, I attended a session at Adelaide Writers’ Week where writers Bri Lee and Lucia Osborne-Crowley appeared. Both are survivors of sexual assault. Lee said that in writing Eggshell Skull (2018) a kind of therapy was enacted through gaining ‘control of every single word’, by deciding ‘what the narrative’ would be. Osborne-Crowley spoke of trauma as calcifying if the story is repressed. In creating her own performance and in the curation of her many narratives, Elagoz is exercising a control denied her by her two rapists. It should be noted that the work was created in 2016, before the #MeToo movement exploded and stories of sexual assault flooded the web.

Let’s pause for a moment on the work’s title. Cock, Cock … Who’s There? We cannot discard the first part. After all, without the cock, there would be no rape in this case. But the title’s real resonance lies in its second part, which might be recast as follows:

‘Who’s There?’

‘Samira.’

Which leaves us with the more complex question of ‘Who’s Samira?’ – a question too difficult to answer. There are a multitude of versions of Samira evident in Cock, Cock … Who’s There?, not as a direct result of being fractured by her experience of rape ̶ which is not to say that she hasn’t been ̶ but because this is who Elagoz is, as an artist, as a woman in the world.

The star system will not be used for the purposes of this review, given that the work emerges from an autobiographical rape narrative. ED.

Cock, Cock … Who’s There? by Samira Elagoz was performed at the Main Theatre, AC Arts, as part of the Adelaide Festival. Performance attended: March 1.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.