Nomadland

Life in the Nevada town of Empire has become extinct: the town’s plant has been shut, the houses emptied, the postcode eliminated. Fern’s (Frances McDormand) husband has died recently, and when we meet her at the start of Nomadland, written and directed by Chloé Zhao (The Rider, Songs My Brother Taught Me), Fern’s sole earthly anchor is a small van in which she has packed all her remaining belongings. She cuts ties with the last of Empire’s residents with a firm hug and a tight smile, then drives off into a vast, frozen landscape. Untied from the comforts and constraints of a stationary life, she navigates a difficult freedom, relying for her livelihood on the fortuity of sporadic employment, free parking spaces, and human decency.

Leaving Empire, Fern coasts from place to place. She brushes paths with the same clapped-out drifters and bulls through low-paying jobs with ease. After ending a seasonal stint in an Amazon fulfilment centre, she finds refuge in a caravan rendezvous in the Arizonian desert, cleaning toilets in an RV park, dishing out canteen food, then hauling potatoes, and on, and on, and on.

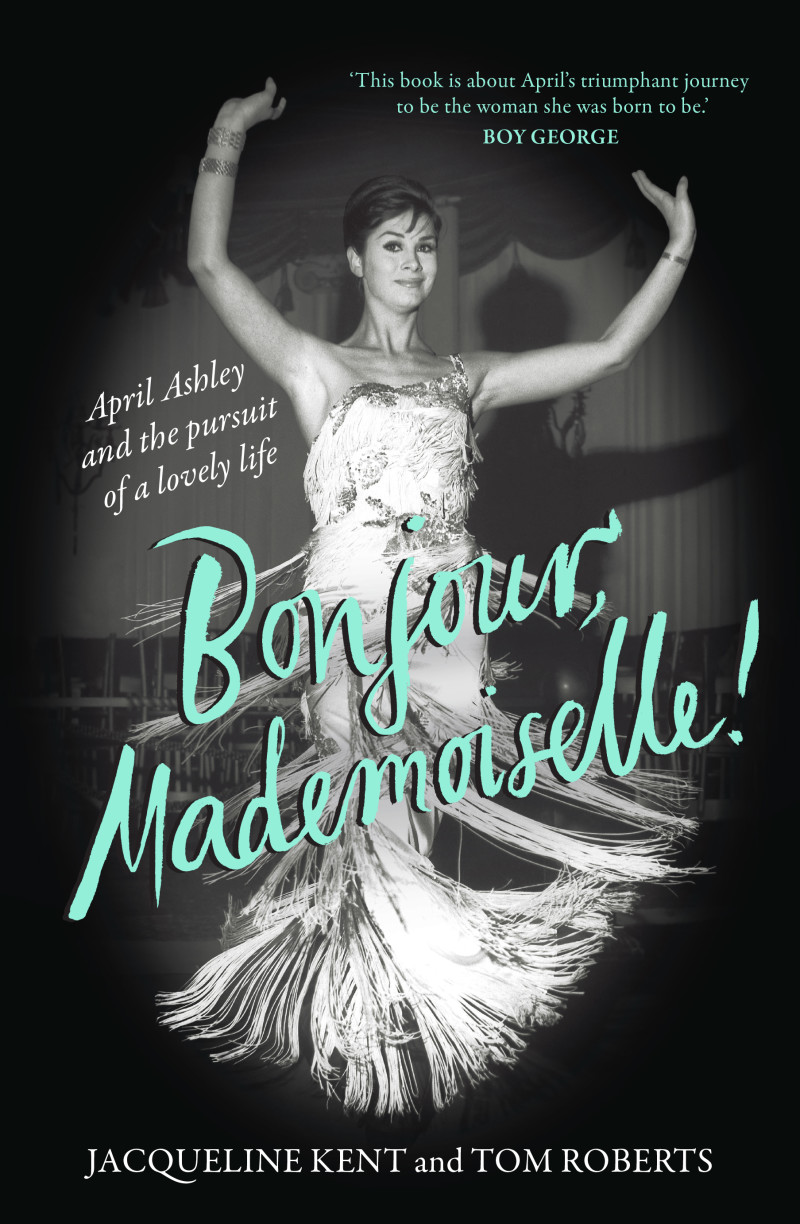

Frances McDormand as Fern in Nomadland (Searchlight Pictures)

The simplicity of a life unmoored from financial and geographical stability lulls Nomadland into a pacifying but propulsive pace. Moments of great emotion are brief, and time flows ruthlessly through the seasons. The film meditates on the rhythm of life’s passing and the inevitability of change, necessitated here by Fern’s vagrancy, the freedom of her compass. Overhead, Ludovico Einaudi’s warm melodies infuse Fern’s itinerant journey with a melancholic dignity.

It’s this holistic angle of Nomadland – Zhao’s eschewal of a constructed narrative, choosing instead to snatch at random aspects of Fern’s post-Empire existence – that lends it a sense of authenticity, the sense that Fern’s life, world, and friends are all indeed utterly tangible. The film itself is adapted from a non-fiction text: Jessica Bruder’s Nomadland: Surviving America in the twenty-first century (2017), which examines older recession-hit nomads who travel across the States in campervans, seeking employment. The documentarian nature of Joshua James Richard’s reverent camera, as it moves almost ponderously across panoramic lands and time-swept faces, imbues the film with the sort of meaning that enriches a life otherwise prosaic. With the exception of David Strathairn (who plays a charming drifter rendered slightly facetious by Straithairn’s celebrity), Fern’s companions are all played by non-professional actors.

These individuals comprise Nomadland’s modest heart. Fern befriends many characters, some with which she shares a few precious soul-baring moments. She exchanges a gift, a cigarette, a name, a tête-à-tête. She meets a septuagenarian woman by the name of Swankie (who plays a fictionalised version of herself). Swankie’s cancer having spread to her brain, she has less than a year to live. She resolves to spend her last days in Alaska, where she saw such sights of nature that rendered her life meaningful and complete. Swankie’s storytelling, as she reflects on a personal history beyond our reach and understanding, is bracingly raw. People like Swankie rise without warning into the foreground of the film, then fade away without fanfare. Throughout Nomadland, it is impossible to tell whether we will ever see these people again, or whether the rest of the film will pass their lives by.

Frances McDormand as Fern in Nomadland (Searchlight Pictures)

Paired with the randomness of Fern’s experiences on the road is the immutable trajectory of her journey deeper into her years, further away from her life at Empire. Nomadland depicts the process of recovering from the loss of a loved one and an entire community. The tragedy of Fern’s vanished life is marked by the solace she finds in various objects – her van, named ‘Vanguard’; a collection of plates gifted by her father; worn-out photographs of people we do not recognise. In one of the first shots of the film, Fern holds a weathered denim coat to her chest, face crumpling. But her past is something we are never allowed to see, though it overshadows everything. The effect is haunting but frustrating; we are following a person’s reaction to a tragedy without having seen the tragedy itself, and it is sometimes difficult to fully empathise. Frances McDormand, however, expertly sustains Fern’s rugged pathos; the hard steel of her spirit is something to behold.

The circularity of the film’s structure – as Fern seeks the same companions, the same rough work, the same modest spans of peace – digs at something universal: the comfort of life’s thematic mainstays. Zhao’s film is backed by its enormity of theme – the unsullied grace of a wanderer’s life, upon which uncertainty, resentment, and tragedy play its part, but so too beauty, companionship, solitude. Its hard-boiled sentimentality is captured by the words of goodbye with which the nomads in Nomadland part, uncertain of the paths of their comrades. ‘I’ll see you down the road,’ they say – be it in this life or the next. These are words that capture the calm acceptance of the drifters, who take everything in their stride and still carry on.

It’s impossible to leave this film with anything but a bolt of awe, a disbelief at the yawning breadth of our world, and the richness of the people within it.

Nomadland (Searchlight Pictures), 108 minutes, screens in cinemas from 4 March 2021.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.