Allen & Unwin

Film | Theatre | Art | Opera | Music | Television | Festivals

Welcome to ABR Arts, home to some of Australia's best arts journalism. We review film, theatre, opera, music, television, art exhibitions – and more. To read ABR Arts articles in full, subscribe to ABR or take out an ABR Arts subscription. Both packages give full access to our arts reviews the moment they are published online and to our extensive arts archive.

Meanwhile, the ABR Arts e-newsletter, published every second Tuesday, will keep you up-to-date as to our recent arts reviews.

Recent reviews

Drown Them in the Sea by Nicholas Angel & The Hanging Tree by Jillian Watkinson

by Lorien Kaye •

Fatal Attraction by Bruce Grant & How to Kill a Country by Linda Weiss, Elizabeth Thurbon and John Mathews

by Jock Given •

There Once Was A Boy Called Tashi by Anna Fienberg and Barbara Fienberg, illustrated by Kim Gamble & The Boy, the Bear, the Baron, the Bard by Gregory Rogers

by Stella Lees •

Well May We Say edited by Sally Warhaft & Speaking for Australia by Rod Kemp and Marion Stanton

by James Curran •

Finding My Voice by Peter Brocklehurst with Debbie Bennett & Wings of Madness by Jo Buchanan

by John Rickard •

Understanding Peacekeeping by Alex J. Bellamy, Paul Williams and Stuart Griffin & Other People's Wars by Peter Londey

by Wayne Reynolds •

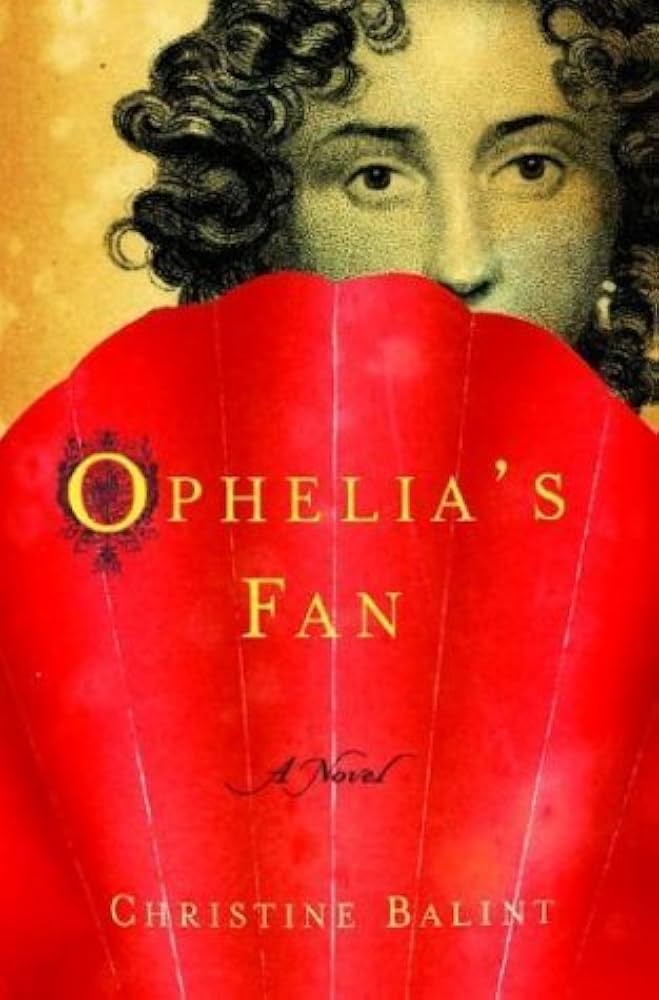

Ophelia's Fan by Christine Balint & Always East by Michael Jacobson

by Carolyn Tétaz •