Picador

Film | Theatre | Art | Opera | Music | Television | Festivals

Welcome to ABR Arts, home to some of Australia's best arts journalism. We review film, theatre, opera, music, television, art exhibitions – and more. To read ABR Arts articles in full, subscribe to ABR or take out an ABR Arts subscription. Both packages give full access to our arts reviews the moment they are published online and to our extensive arts archive.

Meanwhile, the ABR Arts e-newsletter, published every second Tuesday, will keep you up-to-date as to our recent arts reviews.

Recent reviews

Killing Sydney by Elizabeth Farrelly & Sydney (Second Edition) by Delia Falconer

by Jacqueline Kent •

Fake Law: The truth about justice in an age of lies by The Secret Barrister

by Kieran Pender •

In Search of the Woman Who Sailed the World by Danielle Clode

by Gemma Betros •

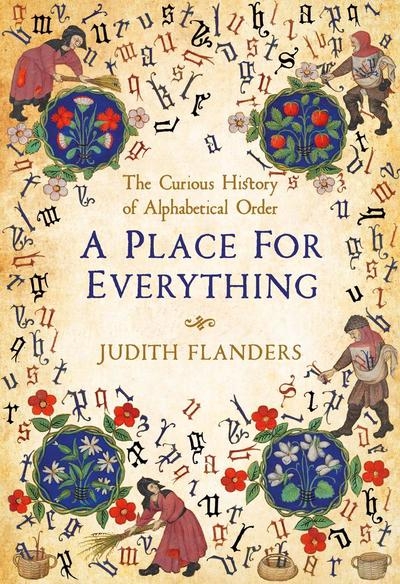

A Place for Everything: The curious history of alphabetical order by Judith Flanders

by Andrew Connor •