Australian Politics

The Victorian Premiers 1856–2006 edited by Paul Strangio and Brian Costar

Gough Whitlam was sometimes naughty. Descending in a crowded lift from a conference attended by a number of state parliamentary delegates, he looked down on his fellow passengers and growled ‘pissant state politicians’. It was the sort of remark he liked to get off his chest. In a more deliberative mood, Whitlam, in his 1957 Chifley Memorial Lecture, wrote of state parliamentarians in the following terms: ‘Much can be achieved by Labor members of the state parliaments in effectuating Labor’s aims of more effective powers for the national parliament and for local government. Their role is to bring about their own dissolution.’ These remarks reflect a widespread dissatisfaction with Australia’s ‘colonial’ constitution and with the division of powers between the three tiers of government. The Whitlam government favoured increased powers and responsibilities for both Canberra and local government.

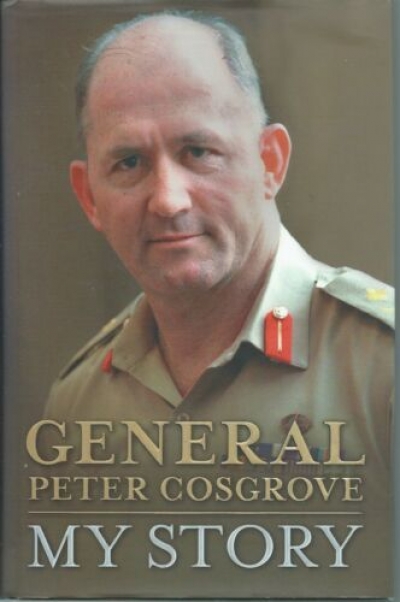

... (read more)General Peter Cosgrove by Peter Cosgrove & Cosgrove by Patrick Lindsay

There is certainly a refreshing candour in My Story and a good deal of pleasant anecdote and humour, but, on the whole, not a lot of ferocity. Cosgrove is most at ease and most readable when he can be convincingly diffident, mocking his own pretensions or, more often, the embarrassing lack of them, as in his account of his arrival at Duntroon Military College. Just short of eighteen, with a ‘lot of growing up to do, both physically and emotionally’, coming off a modest performance in his second try at the Leaving Certificate, with a school track record of larrikin insouciance, the young Peter Cosgrove had every reason to feel nervous as he boarded the bus outside the Canberra station for the short trip to Duntroon. Finding he is sitting next to ‘a fellow who seemed about my age (although years more mature)’, Cosgrove decides to ‘break the ice’. As a result, he discovers that this young man is a product of one of Sydney’s most prestigious private schools, that he had been school captain, a senior cadet, captained the School XV and had been selected for the combined GPS rugby team. Despondently, Cosgrove asks about cricket, assessing himself as ‘no world beater [but] better [at cricket] than at rugby’. His delight in hearing that his companion never played the game is quickly snuffed out when the young man explains that, as stroke of the school eight when his school won the Head of the River, he had no time for cricket. ‘We sat in silence for a moment and then he turned to me and said, “What about you?” I said morosely, “I’m on the wrong bus!”’

... (read more)Michael Gurr was Victorian Premier Steve Bracks’s first senior speechwriter. I am his latest. Gurr worked for Victorian Treasurer John Brumby when he was leader of the state opposition in the mid-1990s. So did I. Gurr wrote the launch speeches for Steve Bracks’s successful 1999 and 2002 state election campaigns. As I type this review, I am also, coincidentally, in the midst of ballpointing my way to the summit of my first draft of the launch speech for the 2006 campaign (a campaign that I cannot know the result of as I type, but you will already know as you read this). The coincidences do not end there.

Gurr’s speech for the 1999 campaign – one made famous by the unexpected defeat of Premier Jeff Kennett – was launched in Ballarat. The 2006 campaign will be launched in Ballarat. Gurr is known in Labor circles as a ‘creative type’ (read: prolific, award-winning playwright of works such as Jerusalem and Sex Diary of an Infidel). I am also known as a ‘creative type’ (novelist and poet). And yet, despite all these coincidences and intersecting lines, not to mention the backbench of associates we have in common, Gurr and I had never met when a speech request landed on my desk a while back with the title ‘Michael Gurr book launch’. Of course, I knew of Gurr. Sort of.

... (read more)Ordinary People’s Politics: Australians talk about life, politics, and the future of their country by Judith Brett and Anthony Moran

Of late there has been a good deal of agitated conversation about the political attitudes of ordinary Australians. As Judith Brett and Anthony Moran point out in this compelling new book, this has often taken the form of a ‘war of words within the political élites’, with the right using its supposed empathy for everyday people as a weapon against intellectuals, and the left blaming the deficiencies of John Howard’s Australia on the narrow-minded selfishness of ordinary voters. As it is, those of us who live in ordinary outer suburbs can hardly open Melbourne’s Age newspaper without finding ourselves accused of something, from a new Australian ugliness and the death of manners to the decline of civilisation. Mind you, the thought of being spoken for by anything-but-ordinary people like Janet Albrechtsen is even more distasteful.

... (read more)The Partnership: The inside story of the US–Australian Alliance under Bush and Howard by Greg Sheridan

If journalism is the first draft of history, this book is a rough-hewn draft of some important historical chunks. Greg Sheridan, the foreign editor of The Australian, may not match some of his colleagues there in gravitas, intellectual depth, or analytical precision, but he compensates with an abundance of enthusiasm and enviable access to those in high office. In the early and mid-1990s, when The Australian was prominent among those boosting Asia and Australian–Asian relations, Sheridan was cheerleader for the boosters. His columns and books were often based on long interviews with presidents and foreign ministers, recounted in a tone more often found in celebrity journalism than in diplomatic reports. Sheridan’s obvious delight at being granted personal interviews with the powerful aroused some envious comments, but his technique served a purpose.

... (read more)Quarterly Essay 22: Voting for Jesus: Christianity and politics in Australia by Amanda Lohrey

In the week that Voting for Jesus landed in my letterbox, the Howard government announced that it was considering dollar-for-dollar support for state school chaplaincies, while, in New South Wales, fresh allegations surfaced of branch stacking by the state Liberals’ ‘religious right’ faction. Those perplexed by such developments in secular Australia will find novelist Amanda Lohrey a helpful, warm-hearted guide. Her colourful, impressionistic and approachable account of Australia’s religious right welcomes readers into a debate that some might previously have been inclined to dismiss as too confusing, or as marginal to secular concerns. Chats with academics, theologians and commentators offer a variety of angles. Far from adopting a didactic tone, the text beguiles with numerous questions that sound rhetorical but often remain unanswered.

... (read more)Reconnecting Labor by Barry Donovan & Coming to the Party edited by Barry Jones

The Liberal Party, in its barren years (1983–96), was consumed in battles over beliefs. The dries took up the cudgels in a war over the nature of liberalism and effectively gained control of the party room. As Paul Kelly has described it, the party torched its Deakinite heritage. John Howard was not central to these battles, but he was the inheritor. His brilliance has been to take the neo-liberal agenda (individualism, choice, markets versus ‘bureaucracy’, the ‘mainstream’ versus ‘élites’), to give it an Australian resonance (by reinterpreting the ‘Australian legend’ as a story of individual battlers) and, relentlessly, to link his profession of beliefs to every policy statement he makes. It is unlikely that most of the punters systematically assess what Howard says in their own voting deliberations, or could complete a test on Howard’s key principles, but impressions have their effects. Recently, when I asked a group whether they thought there was a difference between the parties, a young woman confidently replied: ‘Yes, one party knows what it thinks and gets on with it; the other doesn’t.’

... (read more)The Howard Factor edited by Nick Carter & The Longest Decade by George Megalogenis

The provenance of The Howard Factor – a collection of essays by senior writers from The Australian newspaper – is not promising. The Australian is after all part of Mark Latham’s ‘Evil Empire’, cheerleader rather than critic of the Howard government. Yet its sympathy for the régime stems not from partisanship but from the newspaper’s philosophy: neo-liberal in domestic matters, neo-conservative in foreign policy. Populist desertion of elements of the neo-liberal agenda has aroused the wrath of the newspaper: witness its condemnation of the government’s policy funk in early 2001, and of its recent surrender to Snowy River romanticism. Discord has been less in foreign policy, where both government and newspaper have been willing recruits to the ‘war on terror’. So slavish has become the newspaper’s adherence to America’s contemporary wars that it has even repudiated its quite heroic stance on the Vietnam War a generation ago.

... (read more)Ross McMullin’s Will Dyson is a new edition of a book that first appeared twenty years ago. Over that time, the author has promoted his subject, according to the book’s subtitle, from ‘Cartoonist, Etcher and Australia’s Finest War Artist’ to ‘Australia’s Radical Genius’. ‘Genius’ is a strong word, and the new edition does not make a case for its use any more than the old one did. But Dyson is certainly an important, often unregarded, figure in the history of political cartooning. The story of this talented, likeable, thoroughly political man is well worth knowing on many fronts: as a saga of early Melbourne working-class bohemian culture, as an example of the invigorating effect on English political cartooning by antipodean artists in the early part of the twentieth century (the career of David Low shadows that of Dyson), and as an account of the way that World War I registered on a sensitive, and responsible, Australian imagination.

... (read more)Arthur Tange joined the Commonwealth Public Service in 1942, at a point in time when it was undergoing ‘a permanent revolution at once in the size, the calibre, the philosophy and the significance’ of what it was and what it did. Most Australians now forget, if they ever knew, just how limited the function and reach of federal government was in the first decades of the Commonwealth. As in so many areas of national life, World War II wrought a profound transformation in virtually all aspects of central government and public administration, and the young Tange was in at the beginning of the process. As Sir Arthur Tange, Secretary of External/Foreign Affairs and Defence successively from the 1950s to the late 1970s, he did more in turn to shape the formulation and execution of policy in these two areas than any other official, and many ministers, of his time.

... (read more)