Archive

The Presidents: The transformation of the presidency from Theodore Roosevelt to George W. Bush by Stephen Graubard

by Peter Haig •

Australia: Nation, belonging, and globalisation by Anthony Moran

by Tim Rowse •

A Hand in the Bush by Jane Clifton & Death by Water by Kerry Greenwood

by Jake Wilson •

Australian Literary Studies edited by Leigh Dale & Meanjin edited by Ian Britain

by James Ley •

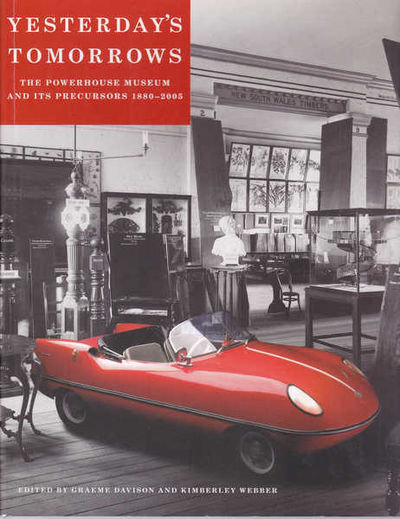

Yesterday's Tomorrows: The Powerhouse Museum and its precursors 1880-2005 edited by Graeme Davison and Kimberley Webber

by John McPhee •

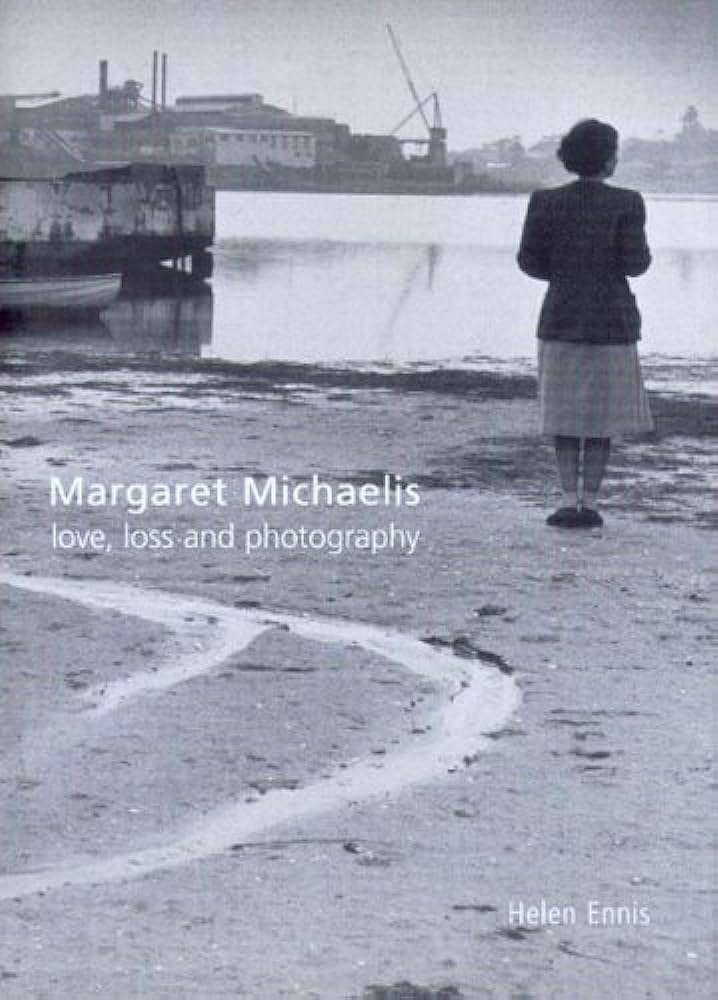

Margaret Michaelis: Love, loss and photography by Helen Ennis

by Evelyn Juers •