Literary Studies

Writing The Story Of Your Life: The ultimate guide by Carmel Bird

While Australian women in particular have been avid diarists and letter-writers, the activity du jour is overwhelmingly the writing of memoir, inspired by the notion that everyone’s life is memorable and worth recording. Some memoirists are searching for the truth of their lives, to recover the past or perhaps recover from it. Some are simply recording their story for family consumption. Others, the more ambitious, are seeking publication and fame. Carmel Bird’s advice to them – ‘Stay young. Stay Beautiful. And maybe climb Everest with your eyes shut’ – is the only pessimistic comment in this whole book.

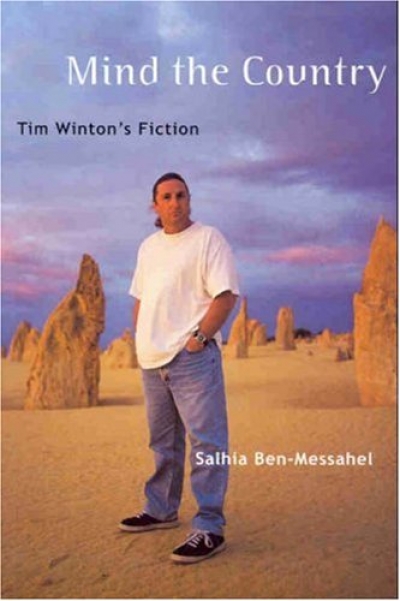

... (read more)Mind the Country: Tim Winton's fiction by Salhia Ben-Messahel

University of Western Australia Press should be commended for recognising a significant gap in Australian literary scholarship: a book-length study on the work of Tim Winton. Aside from Tim Winton: A Celebration (1999; not a critical work), and Michael McGirr’s Tim Winton: The Writer and His Work (1999), written for young readers, there have been no major studies of his work and little critical commentary. Is Peter Craven’s response to Dirt Music (2001) – which he called a ‘profoundly vulgar book’ that ‘bellyflops into a sort of inflated populism’ – widely shared? Is Winton on the nose because he is popular? Certainly, there is nothing sexy about Winton’s work; it embodies wholesome and worthy values, without shying away from stories where these values are absent. But he is a damn good writer – a difficult thing to measure, I know. His work resonates for many people. Whether they adore it or hate it (think Cloudstreet [1991]), people who have read Winton have an opinion on him. Winton’s work, particularly The Turning (2004), prompts interesting questions about contemporary Australian life.

... (read more)The title of Richard J. Lane’s guidebook contains a small allusion to the changes that have occurred in literary studies over the past half-century. There was a time when universities trained critics; these days, everyone is a theorist.

... (read more)The Oxford Book of American Poetry by David Lehman

Thirty years have passed since Richard Ellmann’s magisterial New Oxford Book of American Verse: a hard act to follow. Now David Lehman – poet and founder of the Best American Poetry series – has produced a successor. It is even longer than the Ellmann, and similarly generous in its individual choices. There is no stinting here, no mark of the tyranny of permissions that blights so many anthologies. Walt Whitman gets seventy poems; Emily Dickinson (who published a handful in her lifetime) has forty-three, including the cautionary ‘Publication – is the Auction / Of the Mind of Man’.

... (read more)London Was Full of Rooms edited by Tully Barnett et al.

This digressive collection of essays, extracts, cartoons and poems is unified by an interest in colonial and post-colonial responses to London. It stems from a 2003 conference, ‘Writing London’, organised by Flinders University’s Centre for Research in the New Literatures in English (CRNLE). Part 1 focuses on the Malaysian writer Lee Kok Liang (1927–92), in particular his posthumously published and wry first novel, London Does Not Belong To Me (2003), from which this book takes its name: ‘London was full of rooms. I went from one to the other. Slowly I adjusted myself and lived the life of the troglodyte, learning the tribal customs of feints and apologies.’ Part 2 comprises examples of, and critical and scholarly essays relating to, literary, journalistic, artistic and cinematic responses to London (mostly by Australians).

... (read more)Dancing on Walter Benjamin’s grave, in this book, Michael Taussig is in some ways his reincarnation; born in Sydney in 1940, the same year that Benjamin, trying to escape the Nazis, died in Port Bou, on the edge of the Pyrenees. The dance that Taussig performs is of course a homage to the great intellectual: the most inspired thinker coming out of the Frankfurt school, the most uncompromising, and the most writerly and experimental. Benjamin was a broad thinker, in the best sense. He did not think and write for the benefit of a discipline, but he taught his readers to weave together understandings of contemporary culture, coupled with a Nietzschian sense of history shot through with the ‘profane illumination’ of ancient myths whose impulses always throb in human dreams.

... (read more)Poetry and Philosophy from Homer to Rousseau: Romantic souls, realist lives by Simon Haines

Simon Haines shot to prominence for an Op-Ed piece in The Australian (9 June 2006) that seemed to enter the lists on the conservative side of the debate about what they teach in English classes these days. If you read carefully, you could tell that the prominence was only going to be momentary, because Haines’s argument was far too nuanced to provoke and maintain the level of polarised hysteria the media appears to expect.

... (read more)Old Myths: Modern empires: power, language and identity in J.M. Coetzee’s work by Michela Canepari-Labib

Michela Canepari-Labib is an Italian scholar of English literature and cultural theory. In Old Myths: Modern Empires, she sets out to map J.M. Coetzee’s work onto the major cultural theories of the twentieth century. Coetzee is just as familiar as she with the theories, and no doubt they have had their influence. But anyone can write novels based on Freud and Lacan: what is missing from Canepari-Labib’s account is everything that makes Coetzee worth reading.

... (read more)Windchimes: Asia in Australian Poetry edited by Noel Rowe and Vivian Smith

All regions being regions of the mind, ‘Asia’ has had an especially unsettled and unsettling place in Australian thought. Australia has, in part, defined its own ‘occidental’ status with almost hysterical reference to its many ‘oriental’ neighbours. The putative border crisis of recent times, for instance, involved representing (mostly Middle Eastern and Asian) refugees as cashed-up ‘queue jumpers’ and potential terrorists who were ready to swamp our shores.

Asian ‘hordes’ have long been spectres haunting the Australian imagination. We see them in Windchimes, a marvellous anthology of ‘Asia in Australian Poetry’. But all of the usual suspects are present here, too: Asia as feminine and erotic; as terminally superstitious or spiritually enlightened; as a realm of pure aestheticism; as timeless or primitive; and as a region of war and warriors. All of these tropes, like the idea of ‘Asia’ itself (a region that supposedly ranges from China to Turkey), are as factitious as the notion that Asia is even a distinct continent. So far, so Edward Said, whose Orientalism (1978) made such observations postcolonial clichés. But if we consider the poetry of Australia as it reflects upon the idea of Asia, then we find an exciting literature that both maps and exceeds such tropes.

... (read more)To Exercise Our Talents: The democratization of writing in Britain by Christopher Hilliard

Once the prerogative of connoisseurs and bibliographers, the study of the book has become an increasingly popular field of cultural history. Earlier scholarship was concerned with rare and variant editions of canonical texts; recent work is more inclusive, comprehending a wide range of popular and ephemeral literature that extended the reach of print. Attention has turned from production to consumption, tracing the spread of literacy and analysing the changing interests of readers. Hence Martyn Lyons and Lucy Taksa’s Australian Readers Remember (1992) sits alongside a number of similar studies for other countries.

... (read more)