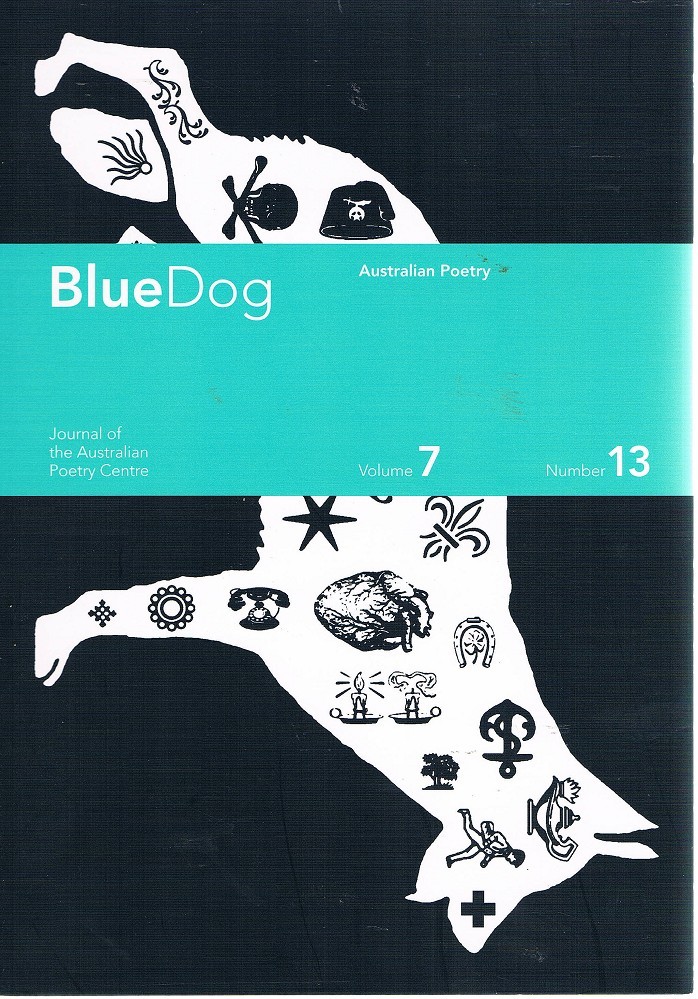

Australian Poetry

Saturday. The usual 9 a.m. flight.

The man beside me hefts a Gladstone.

‘I haven’t seen one of those in years,’

I say, this being sociable Saturday.

I recall a worn one from my twenties

owned by someone else. Always empty

Vincent Buckley edited by Chris Wallace-Crabbe & Journey Without Arrival by John McLaren

Culture Is …: Australian stories across cultures edited by Anne-Marie Smith

When I was a student, the professor used to say that Australian literature had no intellectual content. That was the way professors spoke back then. He might have had A.B. ‘Banjo’ Paterson in mind; Paterson was an enormously popular writer, who didn’t let difficult ideas get in the way. Paterson is the sort of writer who goes straight to the sentimental core of his material. He does not chase after profundities or wrestle with conceptual difficulties.

Paterson could not care less about professorial pursed lips and all that. When, in 1895, his first volume, The Man from Snowy River, and Other Poems, was published, it sold out within a week. Paterson was a sensation, both here and abroad. The Times enthused, and Rudyard Kipling, with whom Paterson was immediately compared, congratulated Angus & Robertson, the publishers.

... (read more)