ABR receives a commission on items purchased through this link. All ABR reviews are fully independent.

Giving up mirrors

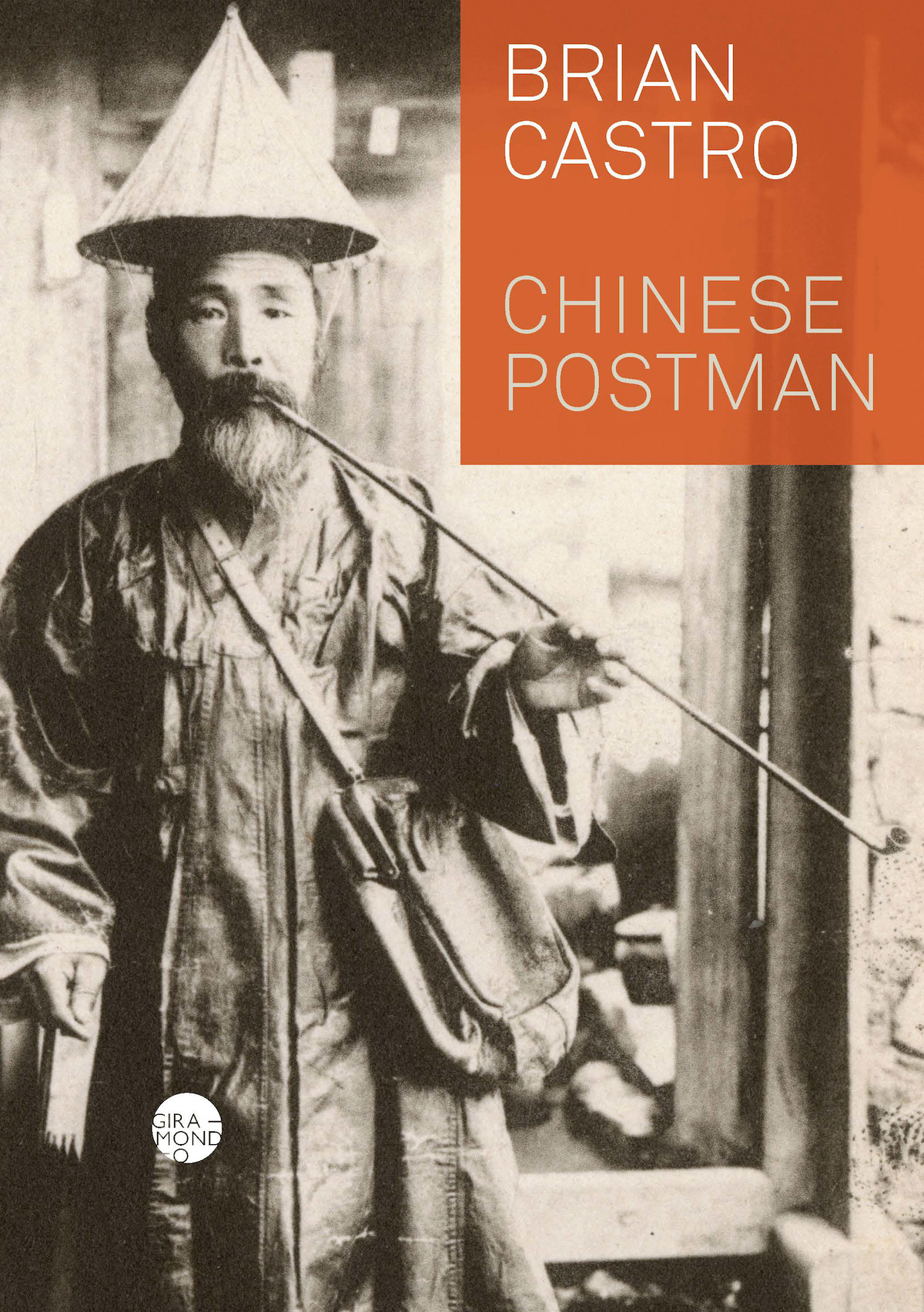

In Street to Street (2012), Brian Castro wrote, ‘It was important that he was making the gesture, running in the opposite direction from a national literature.’ In Chinese Postman, Castro’s protagonist Abraham Quin is ‘through with all that novel-writing; it’s summer reading for bourgeois ladies’. Quin is a Jewish-Chinese former professor, bearing sufficient similarities to the author to function as an avatar. Quin and Castro are the same age, have written the same number of books, and live in the same place (the Adelaide Hills). Sometimes Quin speaks as Quin, sometimes the author chooses to make his ventriloquism evident, and sometimes the identity of the narrator is unclear, but the voice is always raffish, erudite, mercurial.

Not much happens externally, but reading Castro for plot is like listening to Bob Dylan for melody (to repurpose a prime-ministerial philistinism). The belt conveying us through the pages is Quin beginning and continuing an email correspondence with Iryna Zarębina, a woman trapped by the war in Ukraine. ‘To be an epistolarian is not to find solace in written words,’ the narrator claims. Their relationship unfurls like the kirigami flower Quin tosses in a lake. Is Iryna who she purports to be? Can Quin be the man he wants to seem to be?

The book’s true locomotion is the rhythm of the writing, drummed by kinetic sentences with the balance and bravura of Nijinsky. In a period where flat, declarative prose predominates, Castro provides caffeinating playfulness, accretion of rhizomic detail, butt-joining of rarified fragments, and uncanny interiority at no extra cost. The recently departed John Barth said of the novel that ‘[t]he process is the content, more or less’. Chinese Postman provides content as process, with whatever Castro is reading, thinking, or feeling providing grist, but without the superficiality that mars much autofiction.

This could have been the perfect literary bomboniere – typically handsome Giramondo presentation, prose luminous as an Easter moon, studded with jokes sly and shameless: bung on a bow and there’s Christmas fixed. But gravitas saves it from that helium fate. There is grit beneath the shimmer: the financial precarity of dedicated artists; the unbleachable stains of anti-Semitism and sinophobia; the brute realities of war. And, bracketing all, candid admissions of deep melancholy: the indignities of ageing; the timpani-tap of impending death; the fruitless fretting on whether contemporary publication will confer a posthumous foothold in an amnesiac culture.

There is deep pleasure to be derived from Castro’s game-playing – the intertextuality, paronomasia, and detonations of small grenades, paragraphs or pages after the pin has been pulled. Simultaneously, the dizzying erudition and scallywag sensibility can have the reader jumping at shadows. His neighbour is called Paul. A link to the epistolary New Testament chap? Pall, as in smoke from a burning library? Paul is married to Norma who, in Vincenzo Bellini’s opera, had Pollione as a lover. Or is sometimes a Paul simply a Paul? Does hypervigilance for hypercleverness lead to joining-the-dots where no dots were pricked? (Paul’s son is Bartby. Quin describes himself as a scrivener. Paul’s surname is Boswell. Dot, dot, dot.)

It is a novel, not a cryptic crossword, but temptations to pick at the rich encoding abound. Is the name A. Quin an echo of the lamented writer Ann, whose best-known novel Berg (1964) was preoccupied with doubling and upside-downness? When Quin remembers the tragic figure Gong Boy, is it to trigger Qinggong, the Chinese martial art technique for leaping off vertical surfaces? Sometimes he keeps it obvious, such as Pontius Pilate’s being followed by the locution ‘conscious pilot’, or AD (Anno Domino) and HD (the poet) plugging into ADHD. Elias Canetti, mentioned twice, is one spark in a recurring theme of book burning. Quin sets fire to his own library. Given scattered references elsewhere to Warsaw and Kosciuszko, and his penchant for pairing, Castro may be gesturing towards the twice-destroyed Zaluski Library. Or maybe not.

Victor Hugo cautioned, ‘Puns are the droppings of soaring wits.’ (A lovelier translation is ‘Puns are the guano of the winged mind.’) Success or otherwise hinges on personal taste. ‘Shall I wear a nappy rolled? Part my shirt-tail behind?’ Tick. ‘Farting is such cheap callow.’ Cross. There is a recipe for rabbit curry, a riotous anecdote about a disastrous public reading equal to anything in James Kelman’s God’s Teeth and Other Phenomena (2022), and epigrams by the bushel. One, of many: ‘Religion is beautifully built like an automatic rifle and just as universally deadly.’ And yet, the riskiest move for the ironist is sincerity. ‘He lost his perfect pitch and he lost his usual skill in playing with words and coupling etymologies to invent new wakes for old Finnegan … Now, to give up mirrors was the next step: no reflection or signalling; just sit and watch the rain; close the door against ambition.’ His foreigner’s voice ‘jumps here and there and keeps trying to return to somewhere else with the energy of a wren … small and fragile’. Tom Paulin wrote of uselessly intricate sonnets and crossword puzzles: ‘Their bitter / constraints and formal pleasures were a style / of being perfect in despair; they spoke / with the vicious trapped crying of a wren.’ Castro’s despair may be perfect, but the wren is calling gamely to other creatures, and that choice is heroic.

Another remarkable aspect of this novel is the preoccupation with defecation. Castro grounds his eschatology in scatology. The extensive history of faecopoetics embraces Chaucer, James Joyce, Philip Roth, Karl Ove Knausgård, and many others, but it is difficult to recall another book that makes such extensive use of toileting in all its moods and (com)modes. Given Castro’s long-standing interest in Freud, what can be discerned from Quin’s memory that his mother ‘had her little bag of gold always with her’? In ‘Character and Anal Eroticism’ (1908) Freud documented folkloric links between gold and faeces across various cultures, adding, ‘We know that the gold which the devil gives his paramours turns into excrement after his departure.’ Could this apply to Quin’s overtures to his potential paramour? American academic Mary Foltz has argued that literary representations of defecation concentrate the reader’s mind on impacts of waste, environmental and cultural, but this seems too woolly for Castro (although he tenders ‘literary memory grows out of waste, of schadenfreude and shit’). More likely, he wants to highlight what is at stake – everything: life and death – a nod to the popular crudity, ‘If you don’t shit, you die.’ Or maybe he just wants to get on the cans with Manzoni.

In ‘The Uncanny’ (Das Unheimliche, 1919) Freud examined the meaning and significance of the words ‘heimlich’ and ‘unheimlich’, terms Quin/Castro exercises. (When Quin’s dog chokes to death, he is too laggard to save him with the Heimlich manoeuvre.) Freud argued that the idea of an eternal soul ‘was the first double of the body. From having been an assurance of immortality, it becomes the uncanny harbinger of death.’ Quin’s ongoing defecation dramas are a reminder both of mortality, and that he is still alive; whereas his printed words, which will outlast his physical body, might not guarantee being remembered, let alone immortality. Future judgements must remain uncertain. For now, far from being the ‘dried cricket in a matchbox’ he suggests, Castro’s soaring stridulation is an adornment to literature, regardless of the nation of origin.

ABR receives a commission on items purchased through this link. All ABR reviews are fully independent.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.