‘Can’t get enough of the US election?’

.jpg)

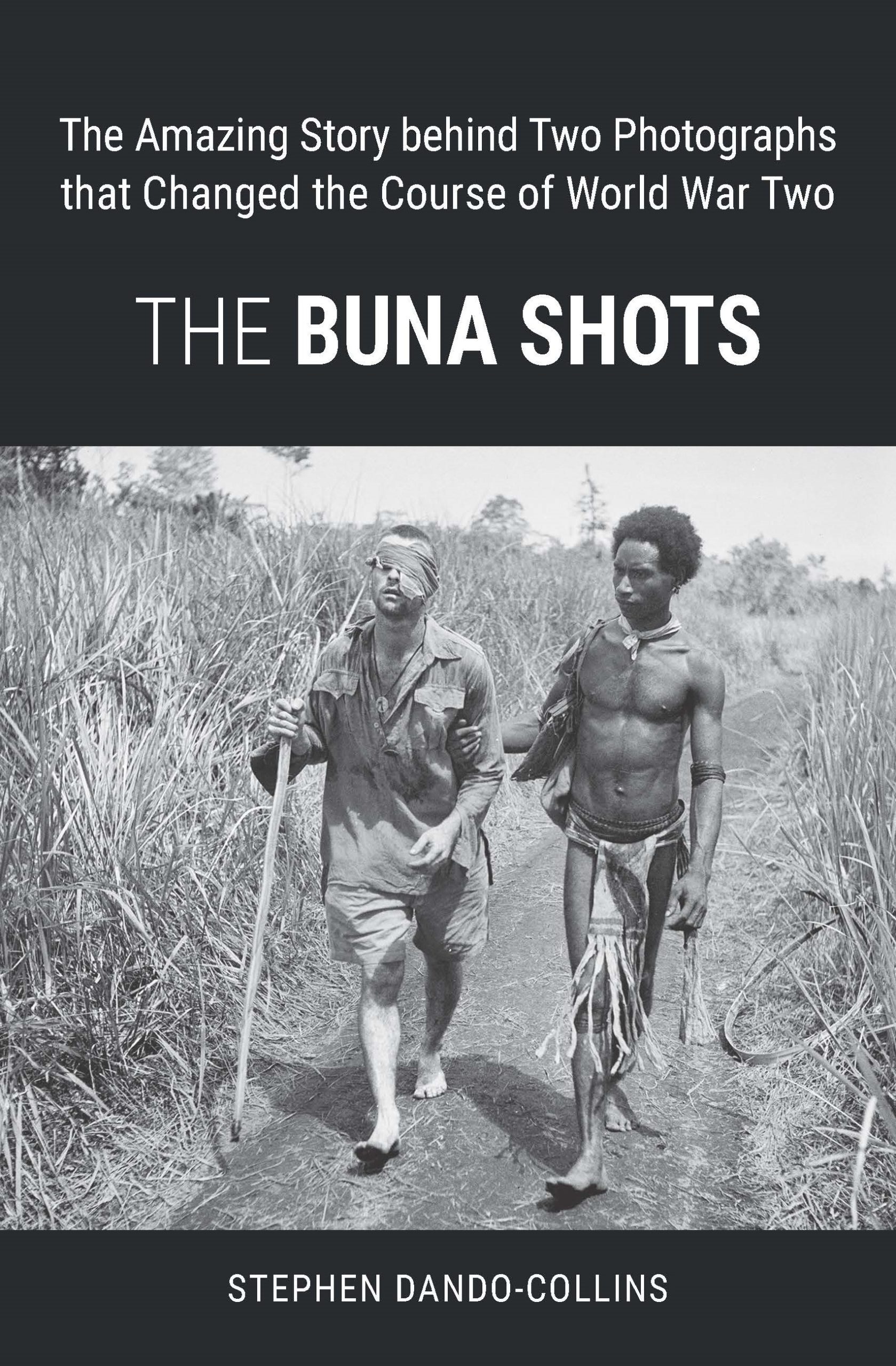

A recent advertisement in The Guardian headed ‘Can’t get enough of the US election?’ prompted reflections on our seeming obsession with the current presidential campaign. Myriad readers follow the contest closely, almost compulsively. On the hour, we check the major websites for the latest polls or Trumpian excesses. In a way, the election feels more urgent, galvanising, consequential, and downright entertaining then next year’s federal election.

Is this near obsession healthy for Australian democracy? Many Australians on the left convince themselves that a Trump victory in November would be disastrous for the world order and the world economy. But will catastrophe or Armageddon follow a Trump victory? Was Australia fundamentally altered or endangered by Trump’s first presidency? If Trump is re-elected, his second term will soon be over. Said to be on the point of moral or constitutional collapse, the US republic will presumably ride on.

Sometimes the obsession with America seems reflexive. Is there a degree of titillation in this absorption? If US politics were more elevated, debate more sophisticated, the obsession would be more comprehensible.

Does this preoccupation with American politics sap our interest in world politics? Media coverage of Africa or Latin America or Indonesia, say, is negligible. In some ways, the recent Indian election was every bit as momentous as the US one, but Australians seemed largely oblivious. Far-right political parties threaten to make gains right across Europe. Should we not also focus on the strife in Sudan, Ukraine, or the Middle East? There is a forgotten pandemic raging around the world: AIDS. When did we last read about that? Homosexuality is still criminalised in many countries around the world. Women are denied education and opportunities in countries that Australia helped to destabilise. The list goes on. Why fixate on America when there is a big, complex, fascinating world out there?

What does it say about Australia – our discourse, our selective media, the health of our democracy – when we allow an almost prurient fascination with the United States to diminish our interest in the rest of the world and perhaps our own national affairs?

We put these questions to some of our most seasoned and thoughtful commentators.

‘Can't get enough of the US election?’ (The Guardian)

‘Can't get enough of the US election?’ (The Guardian)

Clare Corbould

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.