ABR Sidney Myer Fund Fellowship: 'Sweeping Up the Ashes' by Rachel Buchanan

The book in my hand is a Letts Diary, 11B, made in England. The diary is small, no bigger than a child’s hand. It belonged to a boy named Michael Snell. Clearly he loved school; his first entries list the subjects he studied each day. On 23 January 1950 Michael wrote: ‘Had a letter sent went to school … we had our second injection against typhoid fever getting excited.’ On 24 January he wrote: ‘Last whole day in England for quite a time I hope I come back sometime.’ Then his ship sailed. On 25 January, Michael played football on deck with some other children. Next day he played table tennis, shuttlecock, darts. There was no land in sight. ‘Saw Plymouth last we saw of England for quite a time had light tea waiting for High dinner.’

I squint at the tiny pages, trying to decipher Michael’s minute, assured, cursive script. The blue lettering becomes smaller, so that he can accommodate more text. Michael saw North Africa, the Straits of Gibraltar, the Rock itself, a marvellous sight. The sea was calm. Porpoises rose in the water.

3 February: Port Said but it was so windy. You could feel the wind going through you.

4 February: All we could see was land all round us you could see the cactus in the sand and you could see different army camps in the hills. We got up about half past 5 in the morning and we saw some camels and they were smashing.

10 February: When we got up this morning the sea was rocking like anything and we couldn’t walk down the deck without wobbling back and forth.

16 February: Very hot all day. Saw quite a lot of flying fish. Couldn’t go in swimming because I had blisters on my back which were very sore.

23 February: Saw Australian land about half past seven. Got into docks at twenty past and we had to have our passport cards … Some of the preachers from the Methodist Church took us out for the time ashore … then we went to the home and it used to be an Aborigine mission home and we had a smashing dinner there and played cricket.

On his arrival in Sydney on 8 March, Snell was sent to the Dalmar Methodist Home, near Carlingford.

9 March: Woke up at 10 and went and milked the cows and then we went to the school we were going to and we interviewed the headmaster we are starting school tomorrow but I don’t think much of the school but I will be leaving this year.

10 March: (Woke) Today at half past six as usual. I can milk the cows quite well now but I got a splinter in my fingernail the full length of the nail. It weren’t half sore it may go a bit septic now we went to school but we sat on a wooden stool all day without anything to do. Came home and milked the cows.

23 March: Homes here not as good as English homes no order in the Place but still I may leave school in May. I hope so.

2 April: Got up at the usual time at 6 o clock it teaches me to learn to get up early for when I will be a farmer.

Snell starts to leave pages blank. He attends school once a week but otherwise works in the garden, the kitchens, the cowsheds. His mosquito bite goes septic. He feels queer, sleeps all day, develops liver problems. He begins to write a long letter to Sister Mary, back in England. His writing is no longer small and excited. The words seep outwards and break apart down the page. Wet Day. Wet Day. Wet Day. A bit of barbed wire goes through a finger. He has to go to hospital again. The last proper entry is on 31 August. It says: ‘Darkie served. Music lesson.’ Then there are many blank pages with a few very childish drawings and squiggles. One is of a stick figure with an enormous head. The face, if it is a face, looks desolate.

That’s how the story ends. ‘I didn’t write any of the bad things,’ Michael Snell tells me over the phone.

Snell was one of more than seven thousand assisted child migrants who were sent to Australia from Britain after World War II. Like many other survivors of this cruel policy, Snell’s life is now part of a digital documentary web that includes oral history interviews, photographs, and websites, all searchable via the National Library of Australia’s amazing Trove database resource (http://trove.nla.gov.au). The summary of part of the contents of the 2009 interview Snell gave to the National Library’s Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants oral history project reads: ‘chores at the Home, milking, farm work, child labour, schooling, treatment by other school children; discipline at Home; paedophiles.’ It notes that Michael was left-handed. He was punished for that, too.

In November 2009, spurred by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s apology to Forgotten Australians, Snell donated his diary to the National Library. Joanna Sassoon, the manager of the Library’s Forgotten Australians oral history project, met him. When she asked Snell if his children might want the diary, he replied: ‘The government has taken the rest of my life. You might as well have this too!’

Although it does not have a market value – unlike, say, a letter from Christina Stead – the diary is an exceptionally precious piece of writing. Like Cook’s journal, it is an archival object with intrinsic value. The writings of children and of children’s authors are under-represented in most institutions (Queensland’s John Oxley Library is an exception). Snell’s diary is the only known surviving account written by a British Child Migrant. Now it sits, swaddled in bubble wrap and placed in a brown archival box, marked Acc09/183, where it awaits a manuscript number. In mid-2010, the Library listed it as a manuscripts acquisition highlight, a ‘tiny and probably unique childhood diary’.

My essay is not about the Forgotten Australians. It concerns the politics and purposes of collecting the personal papers of Australian writers in the early twenty-first century, a time of impending archival revolution when institutions (and the writers they collect) are stuck between the analogue and digital worlds, the scholarly and the popular, between the aura of material made by hand and the banality, fragility, and uncertain provenance of material made by machine. Yet it feels right to open with Michael Snell. Although he did not choose this path, his journey from Britain meant Michael became an Australian writer, too. His diary’s presence in the archive is a reminder of the significant but little understood power of collectors (archivists, curators, librarians, valuers) and collecting institutions (libraries, archives, museums) to shape national memory, to seek justice, to demand a hearing, to elevate some reputations and erase others, to confer prestige, power, and importance or take these things away, and to control the past itself or at least control the documentary material that historians, genealogists, novelists, film-makers, and others will use to make stories about the past.

Before I perused Snell’s diary I lunched with Sassoon and Michael Piggott, a former University of Melbourne Archivist. Snell’s diary, though sixty-one years old, had spoken to me with immediate clarity and power. ‘That little time traveller,’ Piggott said of the diary. ‘The equivalent on disk would be unreadable now.’ All I needed to read the diary was eyesight and the English language, but, untended, the contents of a sixty-year-old disk would be unreadable and its format obsolescent. ‘Paper, the handwritten, is in a sense more future proof,’ Piggott said. ‘All matter atrophies, but paper is a material that degrades very slowly. In one thousand years, it might fall apart in your hand.’

The two archivists were provocative, stimulating lunch companions. Sassoon said that while high-profile purchases of works of art are often debated in the media, the same is not true of archives. ‘Who is moderating us?’ she asked. Historians and other researchers do not always understand the power record-keepers have, not only to take in a manuscript but also to appraise and describe it, and thus dictate how material might be found. ‘They think it is neutral,’ Sassoon said. ‘They think it all happens by sedimentary accretion. They don’t understand the power of our hand in crafting the shape of what gets preserved.’

We had talked for two hours, and Piggott had boiled the conversation down to three key points jotted down on a bit of paper:

Everything is useful.

But you can’t predict the uses.

You can’t keep everything.

Archives are messages to the future. What is deposited and cared for in archives represents a best guess about what might, in centuries to come, be significant for researchers, society, or individual communities. But future use is wildly unpredictable. It is easy to make a blunder and take in a large archive that then sits, untouched, occupying precious storage space.

Some predictions, though, are prescient. In the 1920s and 1930s, Sydney’s Mitchell Library collected a great deal of archival material relating to the feminist movements of that time, including the women’s electoral movement. ‘These records were untouched for forty years,’ said Paul Brunton, the library’s Senior Curator and a doyen of manuscript collecting in Australia. ‘People might say “why would you collect it if no one is interested in it”, but then came the 1970s and they [the records] are now very important and are starting to inform our history.’

Likewise, in the early 1980s the Mitchell started to collect material related to alternative lifestyle movements, such as communes, alternative medicine, and protest movements. They called it the Rainbow Archive. ‘We were doing it for about fifteen years,’ Brunton said. ‘If we hadn’t collected that material, a lot of it would be gone.’ One of the Rainbow Archive’s items, an original logbook from the Franklin Dam Blockade, was included in the library’s centenary One Hundred exhibition in 2010.

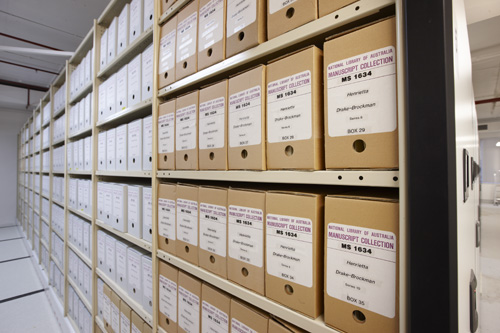

Manuscripts held at the National Library of Australia

Manuscripts held at the National Library of Australia

Such initiatives aside, manuscript collecting is just as likely to both reflect and reinforce the personal preferences of collectors and the broader inequalities of society. The Australian National University’s Noel Butlin Archives Centre and the University of Melbourne Archive are renowned for their business and trade union archives, a legacy of the prodigious collecting and networking of Butlin, ANU’s first professor of economic history, and of Frank Strahan, who became Melbourne University’s first archivist in 1960. In ‘Fathers and Sons’, an exquisite essay published in Meanjin in 2007, Strahan’s son Lachlan described how Frank was ‘driven by an almost religious fervour to preserve Australia’s past, building up one of the largest archival collections in the country. Over the next thirty-five years, the Archives assembled the records of an astonishing array of organisations and individuals from trade unions and companies to missionaries and politicians.’ There is no doubting the Archive’s significance, but it does favour documents about the work and world of men. The Butlin is just the same.

Although there are records of nurses’ and teachers’ unions, two areas dominated by women, the collection is skewed towards the lives of men. In academia, there is also a male bias. The ANU’s Chief Archivist, Maggie Shapley, said that male academics were far more likely to offer their papers for collection than was the case with women, although this might change in decades to come as today’s more equitably balanced academic workforce reaches retirement. The Australian Women’s Archives Project has a register of women’s records or records about women, and encourages women’s organisations to preserve their records.

Marie-Louise Ayres, who has just finished as the National Library’s Senior Curator of Pictures and Manuscripts and become Assistant Director-General Resource Sharing, said the Library’s manuscripts collection had, initially, focused on politics, government, and economics, and was thus still dominated by men, but current collecting was more even. Other imbalances, however, remained. ‘Islamic Australia is invisible in archives and manuscripts,’ notes Ayres.

Like politicians, businessmen, and trade unionists, writers of literary fiction, poetry, and plays enjoy a privileged position in the archival hierarchy. Collecting institutions prize the papers of well-established living literary writers or eminent dead ones ahead of the papers of writers of non-fiction, of genre fiction, of graphic novels, of children’s books, of cookery books, of journalism, of screenplays, or of people who write across the many social media platforms on the Internet. Collectors favour this type of writer, too. According to book and manuscript valuers Peter Pierce and John Arnold, Peter Carey, Patrick White, Tim Winton, Elizabeth Jolley, and David Malouf are among the few Australian writers whose unpublished material is sought after by both individuals and institutions and hence has significant market value. Children’s authors such as Graeme Base, who illustrated their own work, were also sought after. Arnold said lesser-known writers, while important for research purposes, had a more selective collecting audience.

However, writers who are outside the tiny and highly collectable élite can also be paid for their papers by making a donation under the Federal Government’s Cultural Gifts Program. A collection is valued by two of the books and manuscripts specialists on the government-approved list. The donor receives a tax deduction equivalent to the value of his or her gifted work. A collection containing personal correspondence, diaries, and research notes is usually of greater value and interest than one that consists of various drafts of a manuscript.

Seventy-five per cent of the manuscripts at the National Library are donated outright, but writers and composers are more likely to seek direct payment or a tax break. ‘People who make a living from the work rarely offer a donation,’ said Ayres.

With so little funding or time for proactive collection building, it is unlikely that a writer’s papers will be archived and preserved unless he or she approaches an institution. Even among the ranks of noted authors, there are some surprising gaps in collections. The personal papers of Carey, David Williamson, and Jack Hibberd are held in multiple state and national institutions, but no one, it appears, yet holds the papers of Indigenous novelists of national significance such as Miles Franklin winners Kim Scott and Alexis Wright.

Even if a representative collection of writers could, eventually, be built up, who says that writers’ life stories and papers are more interesting, significant, or creative than those of other people, such as activists?

Nick Henderson, a committee member at the community-run Australian Lesbian and Gay Archive in Melbourne, said that the archive has a number of collections of gay liberation material from the 1970s but that personal papers from that period are rare. ‘Back then, it was all about the collective,’ he said. Even so, the archive’s collections tend to include ‘very personal’ content because material is skewed towards the sexual aspects of a person’s life.

And what about scientists? Australia has produced one Nobel laureate in literature, Patrick White, but at least eleven in science (a few more if you include Australian-based academics such as 2011 winner, Professor Brian Schmidt of the ANU). In 2005, pathologist and medical researcher Dr Robin Warren and Professor Barry Marshall were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize for research in physiology and medicine that has led to a big reduction in the prevalence of gastric cancer. The National Library holds Warren’s personal papers. MS Acc07/8 comprises approximately two hundred five-and-a-quarter-inch floppy disks, numbered from V018 to V435. Sassoon, who helped acquire the collection, says these ‘papers’ are vital, but because they are exclusively digital there are challenges with preserving the records and providing access to them. Among the scientific information, the disks also contain the records of the scientist’s other passion – sports tipping. ‘When looking at such archives I take the broad view,’ Sassoon said. ‘He didn’t write beautiful letters, but the collection shows something of the mind that won a Nobel Prize.’

In early 2011, Katrina Dean left her job as Curator of the History of Science at the British Library to become University Archivist, University of Melbourne. Dean said the shift to digital personal papers is challenging for archives because they are found in so many varied media and formats and represent individual ways of working. In London, Dean was part of the British Library’s much-discussed Digital Lives project – an attempt to research and collect digital personal papers, still at the prototype stage. ‘The material was offered to researchers on one stand-alone computer,’ she said.

Dean said that the privileging of writers’ personal papers (whether digital or analogue) over those of scientists arises from a disciplinary issue. A long-established tradition in literature holds that the work is the life and the life the work, whereas scientists regard themselves as much more objective. Why should their life stories matter?

People who offer their manuscripts for donation, though, necessarily believe that their lives do matter. ‘Individual writers or scientists always assume they will be the focus of research,’ said Ayres. But this is often wishful thinking. For example, the library had the papers of an Australian diplomat who had spent a lot of time working in the USSR in the 1950s. The manuscripts had not been used for political or diplomatic histories. Rather, a researcher had used them for a project on food in the USSR in the mid-twentieth century. ‘The diplomat ate out a lot and he kept all the menus,’ said Ayres.

The National Library also holds the papers of Henry Handel Richardson (MS 133). Biographers have mined the papers, but so has Elizabeth Todd, a doctoral student who was researching pain and anaesthesia in the nineteenth century. Richardson’s papers contain material about her parents, Walter (a model for Richard Mahony) and Mary. Walter, a doctor, kept detailed records of his use of chloroform and other early forms of anaesthesia.

A black-and-white photograph shows playwright and novelist Jack Hibberd lounging outside La Mama Theatre, Carlton (MS 12269, State Library of Victoria, Box 2901/5). It is February 1969. Hibberd wears a turtleneck jersey, a pin-striped suit jacket, and the sort of black-rimmed glasses that are once again part of the hipster’s wardrobe. He has a scrawny moustache. Another photograph shows people watching a play. They are sitting on large bunk beds. There are ashtrays and mugs of coffee on small tables. The two actors are in the centre of the frame. The one with the mutton-chop sideburns is grabbing the other one by the collar and appears to be preparing to give him a head butt.

In the Australian Performing Arts Group Correspondence (Box 2901/2), I find an aerogram – thin, pale blue, typed in red ink on both sides, but not dated. It is from John Romeril, St Paul’s Road, Islington, London, to Jack and Joe Hibberd, Alphington. Dear Dr Sin and Spouse, How are you and Joe? Making babies or just wrenching ’em out of other bloke’s wives? The fellow playwright is returning to Australia from London via ‘the interesting half of the world’: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Syria, India, and Afghanistan. He can be contacted, via poste restante, in Istanbul on 3 July and in Beirut on 17 July. I gather you’re unhappy (again) about the way things have gone and that you’ve resigned (you were director weren’t you). I’d like to know why … Where’s the fuck up?

28 April 1972. To the chairman, from Jack Hibberd. Dear Sir, I tender to you my resignation from the collective of APG. I have sent a similar letter of resignation to the executive of the APG. These resignations are quite final. You will probably have read on the noticeboard, by this time, a list of dissatisfactions and some requests. If not, please see enclosed a copy of the list:

Low technical and intellectual standards

Political posturing and hypocrisy

Failure of the actors

Failure to be experimental

Abuse, mis-use and non-use of individuals

Mistreatment of writers

Abdication of directors

Continuing autocratic control of the APG by a power

clique who lurk behind the newly erected mask of collective democracy …

On 4 November 2007 Michelle de Kretser wrote to Jayne Yaffe Kemp, a senior copy editor at Little, Brown and Company, who was preparing The Lost Dog for American publication (MS 13956, State Library of Victoria. Box 2, file 5: 1). De Kretser agreed that American spelling was essential, but wrote:

[Y]ou have made many more lexical changes than I can accept. You say in your covering letter that it’s okay to keep the Australian original ‘here or there’ to retain the flavour but I want my original words retained in the majority of cases. The novel is set in Australia and the characters are Australian (and British and Indian). Your rationale for editing out Australian usage … is American readers will not understand it. I’m afraid that cuts no ice … If American readers don’t know what a banksia or a solicitor is, they can look up those terms, or they can live with the uncertainty …

So much for the lecture! I apologise in advance if I sound grumpy. The USA has so much power, you see, a point it is perhaps impossible to appreciate from outside its borders. We are considerably exposed to your idioms so I am, perhaps, overly sensitive to an apparent un-willingness to tolerate ours.

The Library holds seven boxes of de Kretser’s papers. Quite a few of them are drafts and proofs for The Lost Dog and The Hamilton Case, some marked and annotated, but many not. This is one of a few letters. It isn’t even handwritten (or signed), but the writer’s mark is palpable. It is easy to see why collectors such as Ayres are very interested in personal correspondence and rather less interested in multiple, mostly unmarked, manuscript drafts. The ticking-off is fabulous, but rare. Piggott said that very few of us keep copies of our own letters.

The Library also holds thirty-five boxes of personal papers from Stephanie Alexander (MS 13338, State Library of Victoria). These papers, dating from 1968 until 1998, relate to her famous Melbourne restaurant, Stephanie’s, as well as to her journalism, her many celebrity appearances, and her famous cookery books. There are cards, telegrams, faxes from colleagues and suppliers – which are greasy objects to handle now – and many letters from readers and diners, including former Premier Joan Kirner and celebrity agent Harry M. Miller, whose letterhead reads ‘30 years representing the people who make history’. File 2, in Box 20, is devoted, solely, to ‘sponge recipes received following article in Good Weekend, The Age: 1986’.

Wallet 5, Box 20, contains a letter written by the late publisher Diana Gribble, dated 13 September 1991: ‘Stephanie, I think it’s time I made a serious approach to you to see if you would consider publishing your next book with Text … I’m sure you know I would love to be your publisher, having made a few failed attempts in the past – and I admire your writing enormously.’

File 2, Box 24 comprises five wallets of ‘letters received re restaurant – compliments, insults, etc: 1980–1995’. In early 1985, one correspondent explained that she ‘just about had my baby in your restaurant’. The new mother writes: ‘By the end of the evening I had to go outside and pace up and down while my husband settled the bill. Our little boy was born on Sunday, February 3rd … and we named him Alexander.’

The file also reveals that barristers and medical specialists were the most likely to complain about their meals at Stephanie’s. One man ‘had trouble tasting the goat’s cheese in the warm timbale’; another had a problem with his pigeon terrine, while a third was disappointed by the use of offal ‘and other cheap cuts of meat’ and by the ‘tough, dry and tasteless’ lamb fillet with a ‘bland sauce and greasy zucchini chips’. He claimed that the standard of food and service was unforgivable and suggested that Alexander should send one of her staff to France: ‘to be reminded what French service is all about.’

The chef’s reply, superbly caustic, makes no apologies for the food. ‘I was quite happy with our dish of oxtail cooked with crushed grapes in a superb veal stock as I was with the calves liver sauced with melted butter and crushed sage leaves.’ The letter continues: ‘I am also interested in your suggestion that we have something to learn from France. The 18% compulsory service charge and bill do you suggest?’

Alexander’s archive reveals her industry and the seriousness with which she approaches her writing. It contains forty-one handwritten research notebooks, all indexed. Book 1 includes ‘Good cook = happy shearers’, ‘Gathering nuts in May = demented. Nuts are not ready for harvest in late spring (European)’, ‘Oyster farming – biggest predator is starfish’, and many other elusive, poetic, fragments.

‘I know this might seem a bit odd but I am writing to tell you how much joy I get from the Cook’s Companion,’one reader wrote on 25 November 1997 (20/wallet 2). ‘Your writing style always makes me feel like you are in the kitchen with me.’

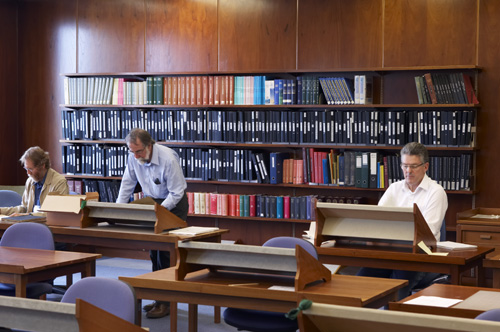

The reading room at the National Library of Australia

The reading room at the National Library of Australia

While politics and journalism are two professions coupled with spin, hyperbole, and sometimes dishonesty and deceit, archives and archivists are almost always paired with the truth. Many novelists use record-keepers or records as a device to enhance the veracity of their fiction. In True History of the Kelly Gang (2000), Peter Carey turned himself into the archivist and publisher of thirteen parcels of soiled, damp, rust-stained, ripped papers, the unpublished writings of the outlaw himself. Barbara Kingsolver’s The Lacuna (2009) is narrated, in part, by an archivist and stenographer, Violet Brown, and based on the notebooks and letters of a Harrison William Shepherd, a writer who once lived in Mexico with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. In the zombie-vampire post-apocalyptic thriller The Passage (2010), Justin Cronin inserts archival documents (diaries, logbooks) into his narrative. The reader is thus assured that some (academic) human beings survive the carnage and then study it at ‘the Third Global Conference on the North American Quarantine Period’.

Martha Cooley’s novel The Archivist (1998) is about an elderly American record-keeper named Matthias Lane, ‘the grey-moustached warden of the obscure Mason Room’, who catalogued a large, sealed cache of T.S. Eliot’s letters and unpublished poems. Michael Piggott pointed the novel out to me (along with several other less literary works, including The Dracula Archives and The Bunyip Archives, ‘set in the dinkum Aussie outback’). According to Piggott, Cooley’s novel had been much praised and quoted within the profession, ‘although some archivists have quibbled its central character is a manuscripts librarian working in a library and wouldn’t behave as he did’. I won’t go into Matthias’s actions here, but let’s just say a deliberately lit fire was involved.

Shocking though it may seem, destruction is an important step in creating an archival record. When records are accessioned, they are often trimmed. ‘There’s weeding, a lot of weeding,’ said Maggie Shapley, Chief Archivist at the ANU. ‘An archivist does not keep everything. We actually throw things out and concentrate on the things that will be useful for research.’ These things included the student files for Kevin Rudd and Bob Hawke, and Manning Clark’s staff file. All these files were prized as ‘impartial and authentic records’ of these men’s lives. Piggott likens this process to firestick farming. To create a good collection, you need to winnow things out.

Records – of individual lives, government departments, publishing houses – are far more likely to be discarded, or damaged through neglect, than preserved. Collecting archives, such as museums, libraries, universities, and libraries, receive more offers of material than they can accept. Rejection helps build their collections. The National Library is offered six hundred collections a year and accepts less than half of this material. The State Library of Victoria receives between two and three hundred offers a year, and accepts about half. Neither institution has the funding to proactively build collections to any great extent.

The decision to accept a manuscript is a complex process outlined in respective collection development policies. At the State Library of Victoria, the Australian manuscripts collection focuses on Victoria and its inhabitants, and aims to ‘record and reflect all aspects of life including politics, the arts, society, business and science’. At the National Library, to be selected for collection manuscripts must have ‘long-term research value’ and national significance. The Mitchell selects manuscripts that ‘document society’.

‘With so many offers, we must make our judgments quickly, rely on instinct – which is really just accumulated knowledge – and try and leave enough of a trail for someone following us to figure out why we said yes or no,’ Ayres said in her 2009 New Norcia Library Lecture. If they reject a manuscript, staff try to suggest an alternative home for it.

Like these public libraries, the Australian Lesbian and Gay Archive in Melbourne is open to all researchers, but ‘where we differ to public collections is that we are a community archive engaging and documenting our community from the inside’, said committee member and professional historian Sarah Rood. ‘We are trying to create a community archive that represents and documents our community and that is as important to us as being a place of and for research.’

Domestic or in-house archives, such as the National Archives of Australia and the state-based public records offices, destroy far more records than they keep, although the way they work is, perhaps, more transparent.These institutions generally select, for permanent retention, no more than ten per cent of the records generated by government agencies. If a ‘disposal freeze’ is declared, though, everything is kept. The current ‘freezes’at the National Archives cover records affecting the rights and entitlements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; records about eligibility to join a Commonwealth superannuation scheme; records about the Vietnam War; and records about atomic testing in Australian territories.

Rood is also on Victoria’s Public Records Advisory Council. She found the first meeting challenging. ‘As an historian I was horrified that, based on the recommendations we made, records would be kept or destroyed,’ she told me. Over time, Rood found that the guidelines were very specific and worked to protect public documents.

Charlie Farrugia, Senior Collections Advisor at Victoria’s Public Record Office, acknowledged how hard it was for record-keepers to please different research communities. Government archivists could not rely solely on the word of the various research communities, however well intentioned. ‘For example, a genealogist would ideally want to see every record with a name on it retained permanently,’ he said. ‘A heritage historian would want to see drawings of every structure built retained.’ Historians were likely to want archives to preserve everything.

Farrugia and Rood were among the guests at a round-table discussion held at Australian Book Review to consider the subject of archivists, archiving, and personal papers. Also present was Professor Ian Donaldson, eminent scholar and former president of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. Donaldson, whose immense research on Ben Jonson is evident in a new biography from Oxford University Press and in the seven-volume Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson (of which he is a General Editor), mentioned that he has a storage room full of related papers. They are, Donaldson later told me in an email, ‘of absorbing interest to me, and of zero interest, I imagine, to the rest of the world’. He also has papers relating to his long international academic career. But he is not sure what to do with them. At the ABR meeting he quietly observed, ‘I am almost at the stage where I will throw everything out.’ It prompted a cry from Ian Britain, historian and former Editor of Meanjin, who is now writing a biography of artist Donald Friend. ‘Oh, don’t do that,’ he said. Britain himself keeps everything, even sticky yellow Post-it notes. During his editorship he preserved all of Meanjin’s correspondence. Peter Rose, Editor of ABR, marvelled at this feat. Of the six or seven thousand ABR-related emails that he generates each year, and the tens of thousands he receives, he preserves a small fraction – those he deems to be of likely interest to future scholars and literary historians.

The University of Queensland’s Fryer library holds 211 boxes of material from novelist Frank Moorhouse. I asked Fryer Library Manager Laurie McNeice if the catalogue listing was right. ‘It’s probably a bit more than that now,’ she said. The catalogue covered material up to 2006, but the library had recently acquired another thirteen large cartons from the writer, ‘the equivalent of another thirty to forty boxes’. The writer had also made an electronic donation of a voluminous batch of emails, but staff had printed them out for safekeeping.

‘It’s true, part of an archivist’s job is selection, but we have to be careful with literary things because even innocuous materials, sometimes, can be inspiration for a book,’ McNeice said. The Fryer also holds David Malouf’s papers. A few years ago, McNeice was cataloguing the latest addition when she found what appeared to be a blank deposit slip from an Italian bank. When she turned it over and looked at the back, the first sentence of The Great World (1990) was carefully written out and extensively revised.

The Fryer collects writers from Queensland or writers with a connection to the state. ‘One of our biggest manuscript collections is Peter Carey,’ said McNiece. ‘We have everything he did up to True History of the Kelly Gang, because he was published by University of Queensland Press.’

The Fryer’s collection is diverse. It holds the papers of major writers such as Malouf and Carey, Thea Astley and Gwen Harwood, and Aboriginal author, poet, and activist Oodgeroo Noonuccal. Its holdings also include a small collection from John Birmingham (relating to his first book, He Died with a Falafel in His Hand), Young Adult fiction writer Nick Earls, and poet–artist Rebecca Edwards. While the Library’s collecting policy is ‘generally conservative and academic’, it also responds to emerging, less orthodox fields of research and writing.With increased interest in genre writers, the library has acquired a large collection relating to romance fiction from academic and collector Juliet Flesch. It also holds the papers of prolific science fiction writer and academic Kim Wilkins.

Other significant collections of writers’ personal papers are held by the national and state libraries, and by specialist collecting institutions such as the Arts Centre, Melbourne’s Performing Arts Collection. The University of Melbourne has important publishing archives, including those of McPhee Gribble, Sisters Publishing, Meanjin, and Scripsi, as well as the personal papers of Malcolm Fraser. Among its publishing-related material, the State Library of Victoria houses papers from Sybylla Feminist Press and Hyland House and early records from Lothian (all three publishing companies are now defunct).

The early records of Angus & Robertson are at the Mitchell. No one, as yet, has acquired Penguin’s archive. ‘Although very important it is possibly too big for one institution to store, let alone catalogue,’ valuer John Arnold said. It might also be too expensive for one institution to acquire from recurrent funding. Both Arnold and Pierce said that material is sometimes offered to libraries for professional appraisal but then withdrawn if the owner is dissatisfied with the independent valuation obtained.

Acquiring, collecting, and preserving material is expensive. In 1986 the Australian Defence Force Academy in Canberra set up the Australian Literary Manuscripts Program. Under the leadership of Lynn Hard, the program bought manuscripts and other personal papers of both ‘established and promising’ Australian writers. It collected Carmel Bird, Lily Brett, Alex Miller, John Romeril, Bob Ellis, and David Williamson, as well as many other writers whose work is now more obscure. The program, bolstered by the English Department’s commitment to the subject of Australian Literature, was uniquely well funded. ‘There were nine of us in English and four secretarial staff,’ said Pierce, who was an academic at ADFA at the time. ‘Now there are three in English and one secretary.’

Those lavish days are over. The library has no money to buy new material and has one staff member to cover special collections (which include writers and military history manuscripts, theses, and rare books). The reading room is only large enough for one researcher at a time.

Unlike ADFA or the Fryer, the National Library of Australia does not have a specific literary collection, although it does hold the papers of many eminent writers and is acquiring literary publishing archives, too. It also has the G.C. Bleeck Collection, Australia’s largest archive of pulp fiction material. In ‘Bleeck House’, an article in a 2002 issue of the National Library News, academic Toni Johnson-Woods explained that Bleeck wrote three hundred novels under twenty pseudonyms, including ‘space operas by “Ace Carter”, westerns by “Johnnie Nelson” and romances by “Jennifer Parker”’. The collection includes three boxes of personal papers, including revealing and inadvertently hilarious financial records.

Bleeck is an anomaly. The Library’s digital archive, PANDORA, includes the diverse websites and blogs published by professional and amateur writers, but the writers whose papers comprise about a tenth of the Library’s 10,500-strong manuscripts collection have mostly produced literary fiction and poetry. Between 2009 and 2011 the library either received new archives or additions to existing archives from writers such as Judith Wright, Helen Garner, Patrick White, Tom Keneally, Kylie Tennant, Sara Dowse, Robert Gray, Roger McDonald, Jack Hibberd, and Vance and Nettie Palmer (whose collection is the library’s most used literary archive). It received a small quantity of papers from Peter Porter. There is also a large collection of papers from Ivan Southall, author of Ash Road (1965), and many other children’s books.

The content of personal papers can be dangerous, explicit, embarrassing, or damning. In a reading room I become a nosey-parker, rubber-neck, spy, eavesdropper, detective, and voyeur, though my behaviour is officially classified as research. Writers or artists (or their families) sometimes protect their privacy by placing restrictions on the material’s use. For example, some files in the National Library’s Helen Garner manuscript collection are closed during her own life and that of her daughter, Alice Garner. Other material can be viewed only with the permission of the donor. Janine Barrand, the manager of collections and research at the Arts Centre, Melbourne, had to ‘email Nick’ before I could get access to the centre’s extraordinary archive of musician, novelist, script-writer, painter, and poet Nick Cave.

But researchers need to be protected, too. The stuff that sits in people’s sheds and attics can, literally, be dangerous and all material taken into the State Library – papers, maps, rare books, paintings, textiles, VHS cassettes, photographs and negatives, vinyl records, and more – has to go through quarantine first. The quarantine area is in the basement, down a corridor lined with tubes and pipes. A man pushes a trolley of boxes. This is a mortuary and we are the undertakers. We are dressing the dead body, picking over the bones, stripping the flesh from them, hunting for some essential kernel in the soggy Nippy’s fruit box salvaged from someone’s garage.

Savina Hopkins, a Senior Preservation Technician, has put an empty Lindt chocolate box on the table. It is like a tray of anti-museum specimens. In it are some of the bugs that have been found in donated items, as well as insects that have been found in the library. These include a silverfish, a cockroach, a field cricket, an African black beetle, and a webbed clothes moth. ‘But most worrying is the silverfish because they attack the paper.’ Older books were stuck together with glue made from animal protein; bugs love to feed on that. A few years ago, library conservators found bubonic plague fleas preserved in the spine of an illuminated medieval manuscript.

‘Often papers have been stored in a garage. It’s a very open environment,’ Hopkins said. ‘Sometimes we open boxes and we can smell the dankness.’ Mould is a serious enemy. It can be pink, blue, brown, but it is mostly black. Untreated, it can re-grow on collection items. Material is treated in either the preservation or conservation rooms. They are small, with big suction tubes [extraction units] in the walls, like the trunks that you use to vacuum the floor in a dirty car. In the mould room, one shelf has material from the Aborigines Advancement League. ‘This has a lot of wet frass (insect droppings),’ Hopkins said. ‘And this looks like staple rust.’

What advice would she give to people at home who want to preserve personal papers? Hopkins barely paused. ‘Sticky-tape is evil,’ she said. ‘We are taking in a donation from a writer at the moment who used a lot of cut and paste technique … the Sellotape is going to fail and it will all be lost. Metal is pretty bad as well. Staples and paper clips that are kept in the garage can be attacked by rust. It can almost eat the paper,’ she said. Never keep records on the floor either because ‘that really is major access for both creatures and moisture’.

Hopkins and her colleagues will soon be working on the collection of Melbourne painter Howard Arkley. Researchers might drool over the stories behind Arkley’s lurid paintings of Melbourne’s postwar brick-veneer homes, but Hopkins has a different take on it. ‘It’s a valuable collection,’ she said, ‘but he used some dodgy glue.’

Three journals written by Nick Cave are wrapped in white tissue, inside plastic bags, inside a flat grey archival box (Collection 2006.019, the Arts Centre, Melbourne). The smallest bag is labelled: ‘notebook, visual journal, by Nick Cave. C. 1987 2006.019.044.’ I unwrap the tissue and hold a small, battered velvet journal in my hand. There is a gold cross on the front and a finger of dark red hair sticks out from the bottom. The object is fetishist, obscene, thrilling. The lock of hair is Sellotaped onto the front page, on top of a picture of Jesus with a bleeding heart. The page is also marked with what look like splatters of blood. A quarantine nightmare! How the hell did all this stuff survive?

Cave made the diary in Berlin, where he lived between 1982 and 1988. Janine Barrand, the Arts Centre’s manager of collections and research, describes Berlin as ‘a period of intense creativity, fuelled in part by Cave’s hedonistic 24-hour lifestyle’. Although performing arts material is notoriously ephemeral and rarely survives the rigours of the road, Barrand said that Cave values his writing: ‘The word means everything.’

Cave pasted pictures of saints on one page and pictures of topless girls on the other. In Nick Cave Stories, which the Arts Centre published in 2007 to accompany its touring Cave exhibition, Barrand explains how Cave trawled through ‘the old Flohmarkt [flea market] of the city, amassing a surreal collection of disparate things: boxes of human hair, bird bones, religious cards and figurines and postcards of cute cats and children, buxom beauties and flowers and angels’. In 1985 he created a notebook titled ‘Sacred and Profane’; the one I am holding is similar. Cave has written, in chaotic red ink, on two pages. ‘At night the streets seem empty but just take a moonlit stroll along until you have been humiliated until you have been shamed until you have been robbed of dignity.’

The singer began writing his first novel, And the Ass Saw the Angel (1989), in Berlin. The Arts Centre has boxes of handwritten drafts, pictures, songs, and colour-coded plot outlines for it. One box contains typed and handwritten drafts for Book 3 of the novel (2006.019.1151). Cave has written at the front: ‘Persist with the first few pages. Please read it through to the end.’

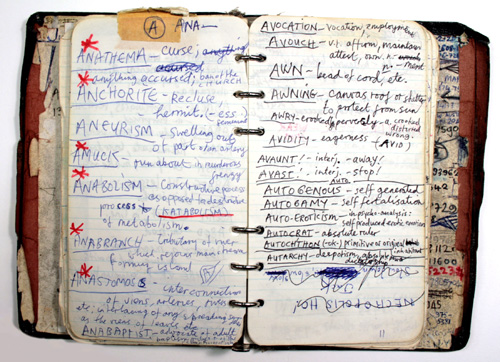

Nick Cave's dictionary of words contained in a notebook, 1984 (the Arts Centre, Performing Arts Collection, Melbourne)

Nick Cave's dictionary of words contained in a notebook, 1984 (the Arts Centre, Performing Arts Collection, Melbourne)

On some pages, the handwriting curls about like a snail trail as Cave plays about with prose that becomes more and more outrageous, Gothic and extravagant. ‘Dumb mute stiff as … a bone, stiff as a virgin’s bone, still as a dead virgin, still as a nun on a slab … stiff as the cold bone of a dead nun, stiff as a monastery morgue.’ There are notes for tour dates, illustrations, tiny scores illustrated with cupids and centurions, and maudlin love notes.

If I could taste Stephanie Alexander’s words, I can positively hear Cave’s. His songs have been part of my life since I was a teenager. I bought my copy of And the Ass Saw the Angel in the foyer of the Brixton Academy in 1991 after hearing Cave play. Now, looking at the unexpected evidence of Cave’s industry and humour, I can hear his songs in a new way, as the poems they are. From a scribble in pencil in the notebook labelled 2006.019.048: ‘I murmured something about loving her till the day I died / She took two pennies and stuck them on my eyes.’ A few lines in blue biro capital letters: ‘I’M GUNNA HURT SOMEBODY WITH REALLY HARD, THIN CHEAP ELECTRIC GUITAR.’ Or this fragment of a lyric (unidentified) typed on cream A4 paper, c.1991 2006.019.107:

Look, this cup of mine is empty

Seems I’ve misplaced my desires

Seems I’m sweeping up the ashes

Of all my former fires

In 2003, Janine Barrand visited Cave at his home in Brighton, England. She asked him if he wanted to relinquish some of his work – lyrics, notebooks, art, photographs – to be used in an exhibition and maintained in an archive. The artist agreed. Three years later, Barrand was sorting through ‘removal boxes hefted around by Nick Cave dressed in one of his beautiful bespoke suits’.

The Arts Centre seeks to develop long-term personal relationships with artists. It has a strong, ongoing relationship with Barry Humphries, who first donated material (scripts, notes, character sketches, and more) in 1979. When his parents’ house was sold, Humphries called the Arts Centre and said the garage – where his manuscript material was stored – needed to be cleaned out.

Until recently, most collections were built in this way, via home visits and negotiations, charm and persuasion, a sort of seduction. In her New Norcia lecture, Ayres explained that it took twenty-five years and the work of four different manuscripts librarians, including Harold White, before the National Library secured the personal papers of Prime Minister Andrew Fisher.

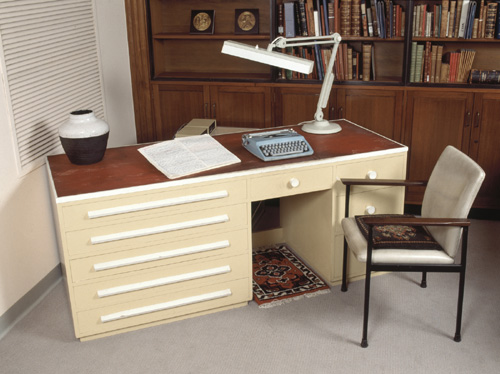

When Patrick White was alive the writer had presented much of his material to the Mitchell Library in Sydney. ‘After his death, I went to speak to Manoly [Lascaris] at the house and he suggested “Why don’t you have the desk?”’ said Paul Brunton, who has worked with archives since 1973. White’s desk is surprisingly modest, as is his typewriter (a portable blue Optima manual). ‘People believe a Nobel laureate will have a grand desk, but it’s not grand, it’s quite penitential,’ Brunton said. White was tall, much taller than Brunton, yet when the curator sat at the desk ‘and put my legs under I am very confined, it is like you are locked into the desk’.

The Mitchell once displayed the desk (XR 54) with a White manuscript – handwritten in blue pen – on top. Brunton recalled being moved by one visitor, who remarked to her young son, ‘You see what you can do with a ballpoint pen and paper.’

Patrick White's writing desk held in the Mitchell Library's archives

Patrick White's writing desk held in the Mitchell Library's archives

I have not seen either White’s desk or his typewriter, but I do arrange to examine a twenty-first-century version of them: the laptop on which Peter Carey wrote True History of the Kelly Gang. The machine is part of MS 13420 at the State Library, but the collection also includes plenty of paper. Box 16 contains letters from signature hunters, fans, fellow writers, translators, and cocky school children who want help with their assignments on Peter Carey. They are readers’ papers as much as writers’ papers. On 27 November 2000, a Fedelma Smith, of Whitley Bay, England, wrote to the Booker Prize winner:

There is a family who go to my church who have the most fascinating habit of pretending I don’t exist … That said, there is one cove who so makes up for it, like, a million times over. I don’t know his name but he is such a giraffe! (Giraffe being the code-word for a cute man, e.g. Oscar Hopkins, Ralph Fiennes, Gabriel Byrne etc). Anyhow you are probably wondering what class of 15-year-old crackpot has decided to pen you her delirious ramblings. It is a budding author, my friend!

Fedelma signed off with a picture of a smiling giraffe. A young James Ainslie opened his letter thus: ‘I understand the busy life you lead and that answering the questions of a snotty year 12 student from Tasmania probably isn’t high on your agenda. I hope the quality of the questions will grab your interest …’

Carey’s laptop is far more fragile than these funny letters. In Controlling the Past (2011), a brilliant collection of essays in honour of American archivist Helen Willa Samuels, Richard Katz and Paul Gandel write about documenting in a digital world.

The emergence of multiple digital media, ubiquitous networks, virtualisation of computation and data storage, open educational resources, open-source software, social networks and the evolving ‘cloud’ of network-mediated services is changing the nature of human interaction, the messages that comprise our collective memory, and therefore the mission, the programs and services of cultural institutions like archives, libraries, museums, colleges, and universities.

At the National Library, the pioneering digital archive PANDORA struggles to collect across multiple websites and platforms. Unlike print, electronic material is not covered by legal deposit provisions, so library staff must seek permission before they can archive websites. Sites such as Facebook or Twitter are particularly complicated, since permission is required from the social-media hosting service as well as from the intellectual rights owners. At present, PANDORA does not archive Facebook pages. The library does not archive WikiLeaks, either. Paul Koerbin, the Library’s Manager of Web Archiving, said: ‘A site like WikiLeaks presents multiple and perhaps intractable legal and technical complexities as well as issues of scope, scale and resource that a national collecting institution perhaps cannot adequately address.’

Even if material is collected, providing access is difficult. In 2010, Twitter signed a deal with the American Library of Congress to collect ‘all the Tweets in the world’, but the library had not yet worked out how the public might read this rather large collection.

Lag is another problem. Most institutions collect from people with established careers. They are often of ‘mature years’, and are not digital natives; although their archives are increasingly salted with digital material, the same material is often also available on paper. ‘They have had to prove their worth,’ the National Library’s Ayres said. ‘They have to be a fairly good bet and many of these people are still archiving paper.’

This means that the true scale of the problem of preserving digital archives for posterity is hidden now but will reveal itself fully in the next two to three decades. Ayres said that by the time an archive or library has identified certain authors worthy of collection – ‘prospects’, as it were – ‘their digital stuff will be long lost’.

‘The big issue for this library is that Australia has no national structure for collecting and preserving and providing access to digital culture and that without that and without significant resources, the existing libraries and archives are not well placed to deal with the issue,’ Ayres said. ‘These are the things that keep us awake at night and that we are most concerned about.’

I asked new Nobel Prize winner Brian Schmidt whether any institution had expressed an interest in collecting his personal papers. No one had, but even if the astrophysicist were asked he would have to decline, ‘mainly because I work primarily electronically, [and] much has been lost and other things are still current’.

The Emory University in Atlanta has acquired Salman Rushdie’s archive, which included four Apple computers. In a 2010 New York Times story on the problems with preserving solely digital material, Patricia Cohen wrote: ‘Electronically produced drafts, correspondence, editorial comments sweated over by contemporary poets, novelists and nonfiction authors, are ultimately just a series of digits – 0’s and 1’s – written on floppy disks, CDs and hard drives, all of which degrade much faster than acid-free paper. Even if those storage media do survive, the relentless march of technology can mean that the older equipment and software that can make sense of all those 0’s and 1’s don’t exist anymore.’

At the State Library of Victoria, digital preservation officer Peter McGrath explained the many challenges involved in working with Carey’s laptop, a late-1990s Apple Powerbook 3400c. First there was the software. The files were created on such an early version of Microsoft Word that they were difficult to read on the 2007 version. Secondly, the computer was so antiquated that the files did not even have extensions (such as .doc). The third issue was authenticity. Handwriting is easy to check and verify, but in the digital world provenance is far less certain.

I listened with interest but was itching to get my hands on the machine itself. This was not possible. ‘We don’t allow access just in case researchers damage or delete files,’ McGrath said.

Rather, the library was going to clone the content on the original machine. In fact, McGrath’s six-year-long search for an exact replica of Carey’s laptop had just ended. We both stared at the ancient black brick on the desk in front of us. ‘I paid $85 on eBay,’ McGrath said. ‘I got it a few months ago and it’s in good working order. It’s from Queensland.’

Manuscripts Librarian Kevin Molloy said the cloning was a one-off and the library would not do it again: ‘True History is a significant Peter Carey novel. Given the mythic status surrounding the Kellys in Victoria, and given the fact that we hold the original Jerilderie Letter which forms the basis of the novel, the historical resonance between the laptop and the Letter was too significant to ignore.’

Exclusively digital material is currently harvested from a variety of mediums and placed on a secure part of the server. At that point a decision is made as to how best to make it available for long-term research. According to Molloy, the Library is investigating options for the building of a digital repository to manage long-term storage, migration, and access to its digital content. In the meantime, there is the silence of the reading room, where I can quietly take your hand in mine and listen.

I proposed this article after spending much of last summer sorting out my late grandmother Norah’s personal papers. In one of the dozens of boxes, I found a red Warwick 2B4 lecture book. Arthritis and age had crabbed my grandmother’s once powerful script. ‘When it is the day before my Funeral I wish the family to gather at Strongyle with the Parish Priest for Prayers and Confessions,’ she wrote. This sentence starts, stops, starts again, is crossed out, edited, rewritten. My university-educated grandmother had become dyslexic. I turned the pages and saw that her writing deteriorated until it was more spidery than the notes we write to our children on behalf of the Tooth Fairy or Father Christmas. Each stroke signalled her terror and her pain and her piety. The shapes she made appeared to match these words: ‘I Love You My God. Your Law is Always in My Heart … Devotion. Meticulous Serenity. Warmth. Kindness. Comforts.’

Interestingly, her menu requests were clearer. ‘Items for Evening Meal. Eggs Poached. Bread. Stewed Apple. Eggs Scramplei. Please Tyr to Provide. Thnk Yo.’

Acknowledgments

Aside from those mentioned in this piece, I would also like to thank Jo Ritale at the State Library of Victoria, Maria Nugent, Graeme Davison, Wilgha Edwards at the Australian Defence Force Academy, the manuscripts staff at the State Library of Victoria, the National Library of Australia and the Arts Centre, Melbourne, Peter Rose and the rest of the team at ABR, and the Sidney Myer Fund (which funded my research through an ABR Sidney Myer Fund Fellowship). Among other published sources, Myer’s extraordinary life is documented in an unpublished biography contained in journalist and novelist Ambrose Pratt’s personal papers (Box 326/1, MS 6504-6634, State Library of Victoria). I am also grateful to Michael Snell and the other writers whose material I have had the privilege of working with.

The ABR Patrons’ Fellowships, funded by ABR Patrons or philanthropic foundations such as the Sidney Myer Fund, are intended to generate fine, incisive writing and to broaden the magazine’s content. ABR will present two or three of them each year.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.