Biography

Unbridling the Tongues of Women: A biography of Catherine Helen Spence' by Susan Magarey

by Helen Thomson •

The Bridge: The life and rise of Barack Obama by David Remnick

by Bruce Grant •

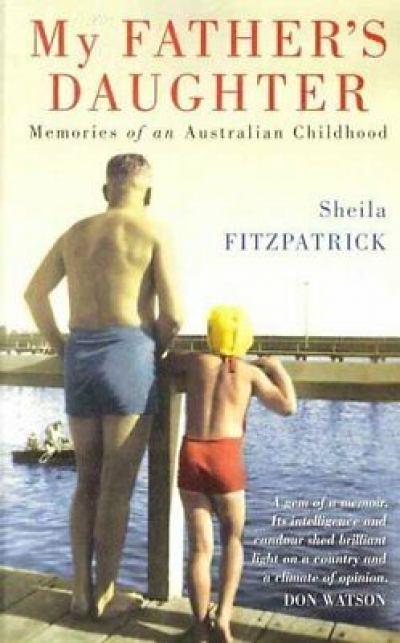

My Father’s Daughter: Memories of an Australian childhood by Sheila Fitzpatrick

by Brenda Niall •

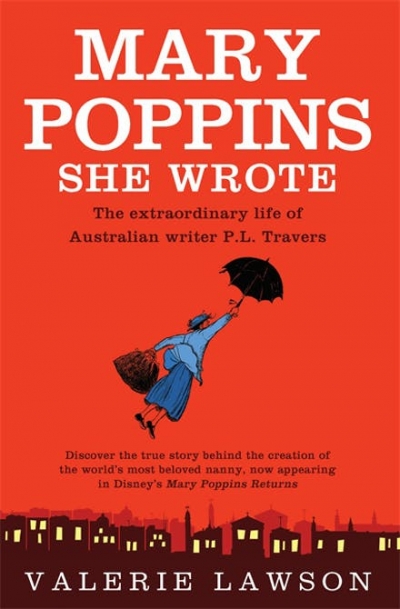

Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The true story of Australian writer P. L. Travers, creator of the quintessentially English nanny by Valerie Lawson

by Lisa Gorton •

Stanley Melbourne Bruce: Australian internationalist by David Lee

by Peter Edwards •

My Congenials: Miles Franklin and friends in letters edited by Jill Roe

by Paul Brunton •