Melbourne University Press

Sign up to Book of the Week and receive a new review to your inbox every Monday. Always free to read.

Recent:

The Blackburns: Private lives, public ambition by Carolyn Rasmussen

The University of Melbourne’s announcement on 30 January 2019 that Melbourne University Publishing would henceforth ‘refocus on being a high-quality scholarly press in support of the University’s mission of excellence in teaching and research’, which led to the resignations of its chief executive, Louise Adler ...

... (read more)Mr Snack and the Lady Water: Travel Tales from My Lost Years by Brendan Shanahan

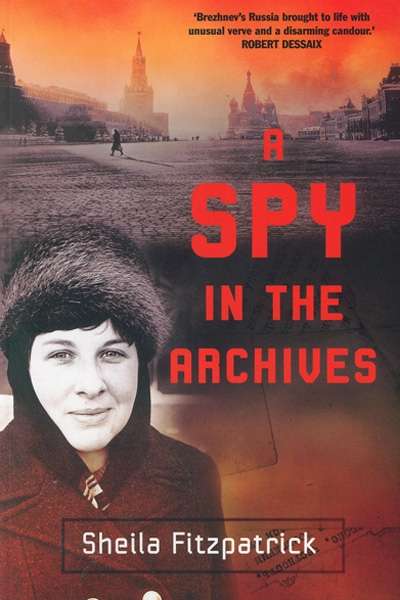

There’s no ASIO file on me, not even a mention in someone else’s file, according to my keyword search. It’s almost insulting, given that I spent several years in the Soviet Union in the late 1960s and later, as a Soviet historian in the United States in the Cold War 1970s, was suspected of being soft on communism. My father, the radical Australian historian Brian Fitzpatrick, had an ASIO file, of course. They even trailed him in the 1950s – or at least trailed someone they thought was him, a man of ‘repulsive appearance’ wearing a hat and an overcoat, neither of which he possessed. He would have been tickled both by the surveillance and the blunder. They had a file on my mother, Dorothy Fitzpatrick, too, although they got her middle name wrong. It wasn’t from her days of real left-wing activity in the 1930s, but from the 1950s, years that were among her most miserable and least political, when she was doing a teachers’ training course at Mercer House and then teaching at the Melbourne Church of England Girls’ Grammar School. To ASIO she was an also-ran to suspected communists of more dominant personality like Gwenda Lloyd; probably they included her mainly because of her marriage to Brian. ‘Same views as her husband’, one informant reported, which hardly does justice to a natural contrarian.

... (read more)