Biography

Alfred Kazin by Richard M. Cook & Alfred Kazin’s Journals edited by Richard M. Cook

by Don Anderson •

The Keats Brothers: The life of John and George by Denise Gigante

by William Christie •

Charles Dickens by Claire Tomalin & Becoming Dickens by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

by Evelyn Juers •

Permanent Revolution: Mike Brown and the Australian avant-garde1953–97 by Richard Haese

by Peter Hill •

Women of Note: The rise of Australian women composers by Rosalind Appleby

by Jillian Graham •

Proud Australian Boy: A Biography of Russell Braddon by Nigel Starck

by John Ellison Davies •

Views From The Balcony: A Biography of Catherine Duncan by Michael Keane

by Desley Deacon •

An Eye for Eternity: The Life of Manning Clark by Mark McKenna

by Norman Etherington •

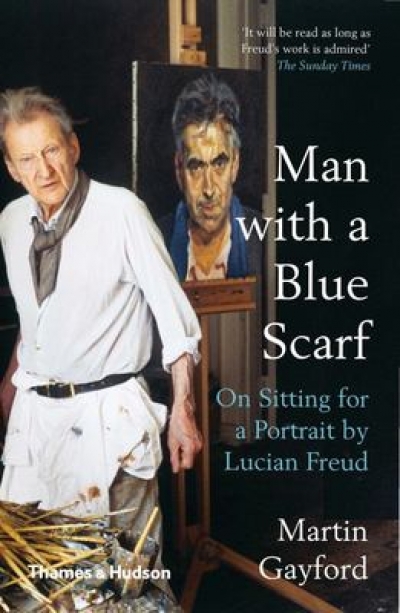

Man with a Blue Scarf: On sitting for a portrait by Martin Gayford

by Angus Trumble •