Features

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics, Fourth Edition edited by Roland Greene et al.

There’s no ASIO file on me, not even a mention in someone else’s file, according to my keyword search. It’s almost insulting, given that I spent several years in the Soviet Union in the late 1960s and later, as a Soviet historian in the United States in the Cold War 1970s, was suspected of being soft on communism. My father, the radical Australian historian Brian Fitzpatrick, had an ASIO file, of course. They even trailed him in the 1950s – or at least trailed someone they thought was him, a man of ‘repulsive appearance’ wearing a hat and an overcoat, neither of which he possessed. He would have been tickled both by the surveillance and the blunder. They had a file on my mother, Dorothy Fitzpatrick, too, although they got her middle name wrong. It wasn’t from her days of real left-wing activity in the 1930s, but from the 1950s, years that were among her most miserable and least political, when she was doing a teachers’ training course at Mercer House and then teaching at the Melbourne Church of England Girls’ Grammar School. To ASIO she was an also-ran to suspected communists of more dominant personality like Gwenda Lloyd; probably they included her mainly because of her marriage to Brian. ‘Same views as her husband’, one informant reported, which hardly does justice to a natural contrarian.

... (read more)On the door to Olive Cotton’s room there is a Dymo-tape label with the name ‘N. Boardman’. Boardman has no relevance whatsoever to Olive’s life story. His name is there because Olive and her husband Ross McInerney’s home – what they always called the ‘new house’ – was previously a construction workers’ barracks. Boardman was one of the occupants, along with Ken Livio and Chris Parris, whose names appear on the doors to adjacent rooms. Olive and Ross, who lived in the ‘new house’ for nearly thirty years, never removed the labels or modified their bedrooms, bathroom, or living areas. This fascinates and perplexes me. Why wouldn’t you erase the signs of those who lived there before you? Why keep them in your most personal, intimate space, your home? What does it mean to live like this? These questions are part of a much larger set arising from my desire to better understand Olive’s life and work, especially during the years when she and Ross lived in country New South Wales, mostly on the property they named ‘Spring Forest’. For much of this time, Olive was invisible to the photography world.

... (read more)The Auckland University Press Anthology of New Zealand Literature edited by Jane Stafford and Mark Williams

Soon after the announcement of the shortlist of this year’s Miles Franklin Literary Award (‘the Miles’), bookmaker Tom Waterhouse installed Anna Funder’s All That I Am (2011) as favourite. Fair enough, too: it’s an astute and absorbing Australian novel about, among other things, Nazism’s long shadow. But Waterhouse favoured Funder – oddly – because her non-fiction book Stasiland (2003) won the Samuel Johnson Prize in 2004. He asserted – debatably, even if it proves correct in 2012 – ‘a strong positive correlation’ between the Miles and the Australian Book Industry Awards. Most interestingly, he noted that the administrators of the Miles, The Trust Company, have now authorised the judges to extend their interpretation of Australianness beyond geography.

... (read more)The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth-Century American Poetry edited by Rita Dove

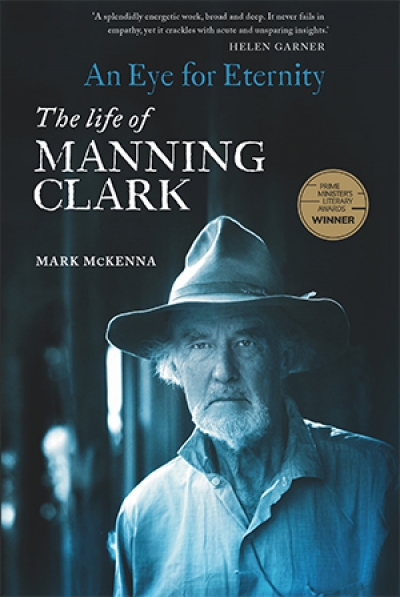

An Eye for Eternity: The Life of Manning Clark by Mark McKenna

With 1086 pages of poems and critical biographies, Australian Poetry Since 1788 – the third anthology co-edited by Robert Gray and myself – is by far the largest anthology of Australian poetry to date, and at least twice the size of its predecessors. Perhaps controversially, it has fewer poets than many earlier anthologies, with only 174 named poets. But it covers the gamut of Australian poetry, including convict and bush ballads, translations of Aboriginal songs, humorous verse, concrete poetry, and generous selections of Australia’s major poets and of the younger contemporary poets. We have tried to be catholic, rigorous, and objective, while listening carefully (with our very subjective ears) to the many different voices from which we had to choose.

... (read more)