Michael Farrell

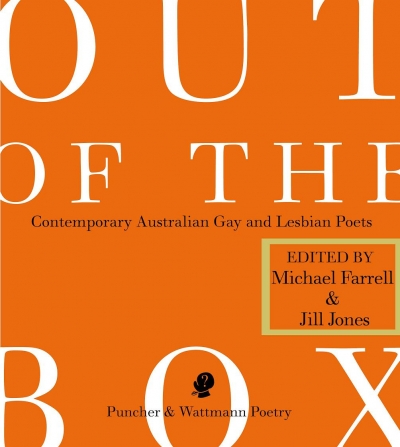

Out Of The Box: Contemporary Australian gay and lesbian poets edited by Michael Farrell and Jill Jones

by Gregory Kratzmann •

Crab & Winkle: East Kent & Elsewhere, 2006–2007 by Laurie Duggan

by Michael Farrell •

the gardens dyed silver. finally he was

less keen like an eaten bird, it wasnt my thing

the path diverged off course to a camp.

you were willing to grow a pomegranate inside.

here they were gods people with their quiet domestics,

the redheads were nicer however. the pram, was full with a baby,

‘dreaming’ of white museums. & white art.

... (read more)