Journalism

Dial M for Murdoch: News Corporation and the Corruption of Britain by Tom Watson and Martin Hickman

Reporter: Forty Years Covering Asia by John McBeth

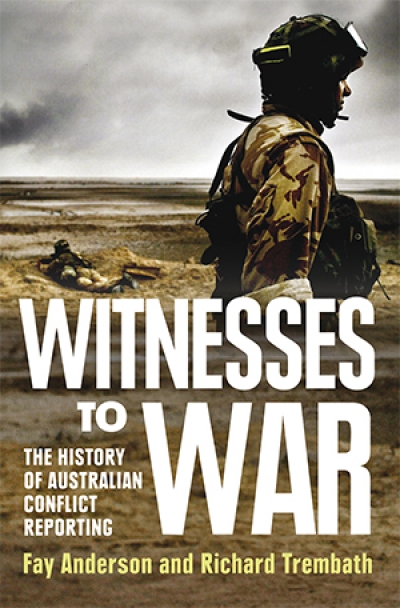

Witnesses to War: The History of Australian Conflict Reporting by Fay Anderson and Richard Trembath

Man Bites Murdoch: Four Decades in Print, Six Days in Court by Bruce Guthrie

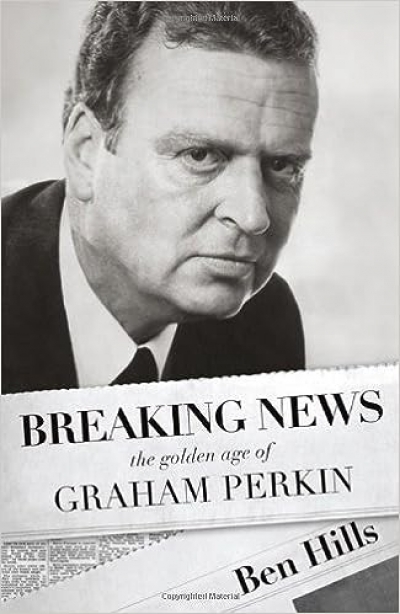

Breaking News: The Golden age of Graham Perkin by Ben Hills

John Reed would have relished it. He could have stood in Times Square in mid-October and watched as the neon newsflash chronicled the fall of capitalism as we know it. And felt the tremor. The difference now is that the ripple effect of seismic events spreads almost instantly. As Wall Street gyrated, banks in Iceland collapsed, and British police departments and local councils faced billion-dollar losses because their investments in Iceland had suddenly gone sour. British bobbies investing in Icelandic banks? Why on earth? That’s a wisdom-in-hindsight ques-tion, of course, but wisdom has been running so far behind delusion for decades that one wants to ask it anyway. Thomas Friedman began his New York Times column for October 19 by asking, ‘Who Knew? Who knew that Iceland was just a hedge fund with glaciers? Who knew?’ His repe-titions underscored the absurd face of the financial tragedy. The implications of the question – who is responsible? – reverberated around the world.

... (read more)