Film Studies

Law at the Movies: Turning legal doctrine into art by Stanley Fish

by Richard Leathem •

The Fatal Alliance: A century of war on film by David Thomson

by Kevin Foster •

Kubrick: An odyssey by Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams

by Peter Goldsworthy •

God and the Angel: Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier’s tour de force of Australia and New Zealand by Shiroma Perera-Nathan

by Michael Shmith •

Film Music: A very short introduction, Second Edition by Kathryn Kalinak

by Richard Leathem •

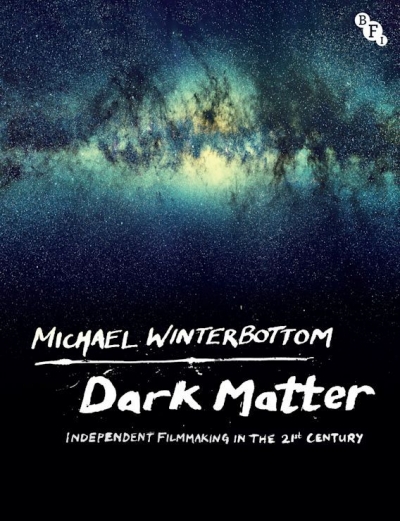

Dark Matter: Independent filmmaking in the 21st century by Michael Winterbottom

by Felicity Chaplin •

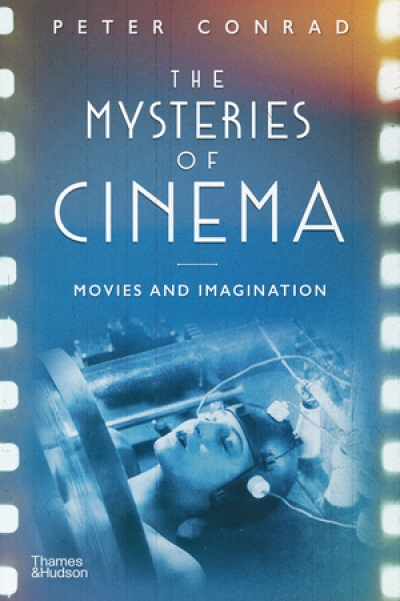

The Mysteries of Cinema: Movies and imagination by Peter Conrad

by James Antoniou •