David Jack

Annihilation by Michel Houellebecq, translated from the French by Shaun Whiteside

War by Louis-Ferdinand Céline, translated from the French by Charlotte Mandell

Cacaphonies: The excremental canon of French literature by Annabel L. Kim

Interventions 2020 by Michel Houellebecq, translated by Andrew Brown

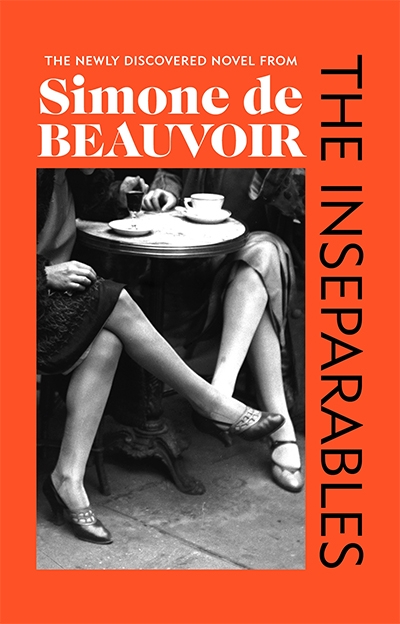

The Inseparables by Simone de Beauvoir, translated by Lauren Elkin

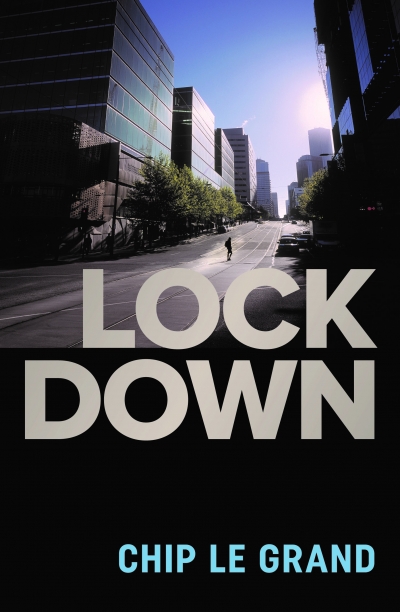

Italian political philosopher Giorgio Agamben’s diagnosis of the condition of ‘bare life’ has assumed a new significance during the coronavirus outbreak. A new book, Where Are We Now? The epidemic as politics, collects some of Agamben’s most thought-provoking commentary on the politics of state responses to Covid-19. In today’s episode, David Jack reads his October article ‘Bare life and health terror’, in which he applies some of Agamben’s key insights to Australia, arguing that the philosopher’s willingness to speak up for the preservation of the foundations of civic life offers a tonic to the atmosphere of alarmism and the new medically endorsed state of exception.

... (read more)In the allegory of the cave, Plato hypothesised the birth of the philosopher as one who emerged from the darkness of illusion into the light of truth. In the dark days of the Covid-19 pandemic, philosophers are finding a platform, mostly in the press, indicative perhaps that we need an interpretation of what is happening around us beyond that offered by the media and daily conferences. As with Plato’s philosopher, what they have brought back is not necessarily what we wanted to hear, and some have been threatened with pariah-like status for views that sometimes run counter to the prescribed consensus. This was certainly the case with Italian political philosopher Giorgio Agamben.

... (read more)