Archive

Two Nations: The causes and effects of the rise of the One Nation Party in Australia edited by Robert Manne

by Dennis Altman •

The MUP Encyclopaedia of Australian Science Fiction & Fantasy edited by Paul Collins

by Damien Broderick •

The Oxford Literary History of Australia edited by Bruce Bennett and Jennifer Strauss

by Andrew Riemer •

Author! Author!: Tales of Australian Literary Life edited by Chris Wallace-Crabbe

by Peter Steele •

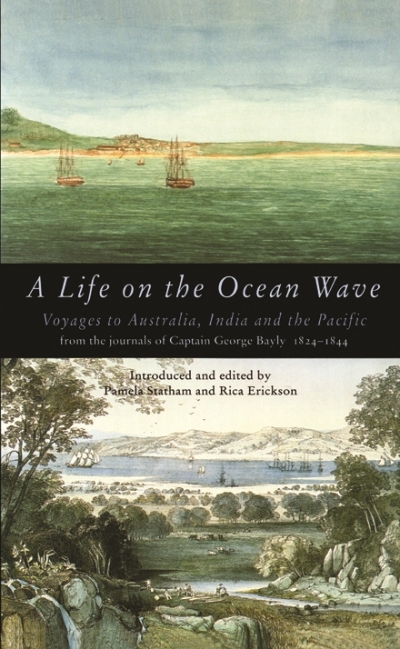

A Life on the Ocean Wave: Voyages to Australia, India and the Pacific from the journals of Captain George Bayly 1824–1844 edited by Pamela Statham and Rica Erickson

by Greg Dening •