Archive

Vale Jacob Rosenberg (1922 – 2008)

The presence of octogenarians and even nonagenarians on publishers’ lists is one phenomenon of the age. Sybille Bedford gave us her exotic memoir, Quicksands (2005), in her ninety-fourth year. P.D. James, aged eighty-eight, has just published another novel, The Private Patient.

The Melbourne writer Jacob Rosenberg, who died on October 30, was not quite that old, but in some ways he seemed as old as the accursed century that he wrote about so memorably. Rosenberg was born in Poland in 1922. During World War II he was confined in the Lodz Ghetto, then transported to Auschwitz. In 1948 he emigrated to Australia with his wife, Esther.

... (read more)Geordie Williamson reviews 'Wanting' by Richard Flanagan

For the inhabitants of mainland Australia, ‘history’ is often complicated by the sheer fact of geography. Instead of one central node, European colonisation expanded from multiple centres, each isolated in space and founded on differing socio-political premises over staggered periods of time, and each with populations too various in background to allow much in the way of agreement about some völkisch collective past.

... (read more)Adrian Mitchell reviews 'The Independence of Miss Mary Bennet' by Colleen McCullough

It is quite extraordinary how often in this country we resort to caricature in our cultural expression. Think of the hammy acting in Australian films and television, the switches in levels of reality in Patrick White’s novels and plays, the new lead William Dobell gave to modern Australian painting or Keith Looby designs for Wagner. Peter Carey has made his fortune from it; Bill Leak has made it his trademark. And no, we won’t start on the politicians, thank you.

... (read more)‘Ice is everywhere,’ observes the narrator of Ice, Louis Nowra’s fifth novel, before succumbing to a bad case of the Molly Blooms and giving us a few pages of punctuation-free interior monologue. No wonder he’s so worked up: ice, in Ice, really is everywhere. It is subject, motif, organising principle, and all-purpose metaphor; it is death, life, stasis, progress; it is seven types of ambiguity and then some. For variety’s sake, Nowra occasionally wheels out a non-frozen alternative – taxidermy, waxworks – but the design is clear: these are merely different nuclei around which the same cluster of metaphors gather.'

... (read more)In early 2018, Christos Tsiolkas published a long essay as part of a series commissioned by the Sydney branch of PEN, an organisation dedicated to freedom of expression. ‘Tolerance’, which appeared in Tolerance, Prejudice and Fear (2008), is an interesting document, not least for the way it highlights how compelling yet exasperating a writer Tsiolkas can be.

... (read more)Just before I flew to Australia to deliver this year’s HRC Seymour Lecture in Biography, I heard an ABC broadcast on the BBC World Service. The Australian commentator was talking about the centenary of the birth of Donald Bradman, the ‘great Don’ with his famous Test batting average of 99.94 runs. He said that Bradman was a peculiarly Australian role model because he was a sporting hero and because he knocked the hell out of the British bowling. Slightly carried away by the moment, he added: ‘We still need those founding fathers – we’ve had no George Washington, no Abraham Lincoln ... Don Bradman fills a biographical gap.’

... (read more)Lisa Gorton reviews ‘Children’s Literature: A reader’s history, from Aesop to Harry Potter’ by Seth Lerer

‘Dress me and put my shoes on; it is time, it is the hour before dawn, so that we should get ready for school.’ This colloquy, probably from Gaul in the third or fourth century, prescribes the ideal child’s conversation, from waking and greeting his parents politely to walking home, with his slave, from school at noon.

Seth Lerer’s history of children’s literature starts with papyrus and ends with Harry Potter. It is called a ‘reader’s history’ because Lerer does not only look at literature written for children – a comparatively recent phenomenon. He also looks at what children actually read: abecedaria, excerpts from Virgil and Homer, versions of Aesop, lists and plays, folktales, prayers and psalters, boy scout manuals, magazines, and chapbook versions of Robinson Crusoe.

... (read more)‘A ‘Change Election’: The US presidential campaign’ by Don DeBats

It has been an extraordinary political war. Conventional wisdoms and long-standing assumptions have flown out the window. The final choice is remarkable: a young, ‘cool’ and detached African American who abjures commitment versus a decided, indeed hot-tempered, maverick whose entire essence is commitment. Long gone is the ‘inevitable candidate’ whose gender is now represented on the opposition ticket, as a vice-presidential candidate no one came close to predicting.

... (read more)I hesitated before deciding to see Summer of the Seventeenth Doll at La Boite in Brisbane this year. Revivals, even under ideal circumstances, can be chancy. The author, Ray Lawler, had reservations about the presentation of his signature work in the round, and so did I. More than fifty years had passed since he wrote it and since I saw it performed behind a conventional proscenium arch in Brisbane, with Lawler himself playing Barney. A story about manual cane-cutters would seem to my children as remote in time and place as one about stokers on a steamboat would have to me, when I first saw the play. Then, there were few, if any, mechanical cane harvesters. There was still plenty of work for rural, manual workers. These were hard, strong men who bankrolled themselves in the season in order to take their leisure afterwards in the big smoke: not just cane-cutters but also shearers, drovers, fencers, fruit pickers and contract miners in Mount Isa and Kalgoorlie and Broken Hill and other distant places.

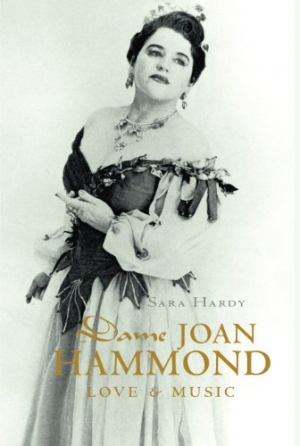

... (read more)Sylvia Martin reviews 'Dame Joan Hammond: Love and Music' by Sara Hardy

My mother, a fine mezzo soprano, had three all-time favourite singers: Kathleen Ferrier, Maria Callas and our own Joan Hammond. When I was a child, my parents took me to see the famous diva perform Tosca in Melbourne – standing room only at the back of the circle. I remember red velvet, a thrilling voice, my own tired legs and a sense that I was in the presence of greatness. Sara Hardy’s biography of Joan Hammond (1912–96) is a timely publication. The number of people who remember the Australian soprano is dwindling, her fame eclipsed by another Dame Joan (who once, early in her career at Covent Garden, understudied Hammond in Aida).

... (read more)