Adriana Lecouvreur

Francesco Cilea’s (1866–1950) most successful opera, Adriana Lecouvreur (1902), is a work steeped in melodrama and the theatrical, but there was perhaps a little too much ‘drama’ at the première of Opera Australia’s production on Monday night.

Cilea’s opera must rank highly among those works that commentators frequently disparage, while audiences continue to stream into theatres to enjoy full-blooded melodrama and full-throated vocalism. Cilea is close to being a one-hit wonder – his L’arlesiana (1897) is occasionally dusted off – but Adriana is certainly part of the repertoire, especially when there is a renowned soprano and tenor in the vicinity.

Cilea’s intended path was the law, but in 1879 he gained entry to the Naples Conservatory where he flourished alongside fellow student, Umberto Giordano, of Fedora and Andrea Chenier fame. Cilea’s first success came with L’arlesiana, a setting of a play by Alphonse Daudet, to which Bizet wrote incidental music, still popular. Cilea started work on Adriana in 1900, with a libretto by Arturo Colautti based on the play Adrienne Lecouvreur (1849) by Eugène Scribe and Ernest Legouvé.

The play itself is based on the historical character Adrienne Lecouvreur (1692–1730), a French actress of great contemporary renown. She is often credited with developing a style of acting that transformed the then current declamatory mode, opting for a more natural and realistic portrayal of character, employing everyday speech rhythms. Contemporary commentators applauded her empathy and accessibility with audiences. Charles Collé (1709-1783) remarked that ‘she makes us forget the actress’; through her developing ‘all the details of a role … we see nothing but the character she represents’. The thespian’s death remains shrouded in mystery. Several theories posit that she was poisoned by her rival, the duchess of Bouillon, but this has not been established by historians. Apart from several other operas, at least eight films have been based on her life, with actresses from Sarah Bernhardt to Joan Crawford embodying this fascinating figure.

Cilea’s opera was premièred at the Teatro Lirico in Milan in November 1902, with a stellar cast, including Angelica Pandolfini in the title role, and with Enrico Caruso as Maurizio and Giuseppe De Luca as Michonnet, two of the biggest stars on the Italian opera stage. Performances soon followed in Europe and the United States, and the opera has never dropped out of the repertoire. The work comes at a transition point in Italian opera with the end of the bel canto tradition; Verdi’s final opera, Falstaff, premièred nine years earlier. A group of composers emerged in Italy in the 1890s, including Cilea, Giordano, Leoncavallo, Mascagni, and Puccini, all of whom remained loyal to a tradition of opera favouring subjects of passion and melodrama which resisted the gradual emergence of modernist tendencies. Many of their works came to be classified under the term verismo.

However, Adriana might be seen as a post-verismo work, part of a sub-genre that engaged with more complex plots where the music sometimes plays a secondary role to the action. These operas often drew directly on stage works for their source, a strategy known by the German term Literaturoper, with Puccini’s Tosca (1900) as the most celebrated example. Adriana is always strongly aware of its own theatricality, revelling in the nuts and bolts of theatrical performance, with much of it set backstage at the Comédie-Française, including a short ballet, The Judgement of Paris.

Adriana has a complex plot, sometimes difficult to follow, but despite this the opera has never waned in popularity, one of the main reasons being the insistent lure of the title role. An illustrious roll-call of sopranos have been drawn to the sumptuous, luscious vocal challenges and delights of Adriana, as well as the tantalising histrionic possibilities it offers. Rather unkindly, the role has sometimes been characterised as best suiting a singer slightly past the high point of her career. Adriana has a limited range when compared with some of the other major roles in the Italian lyric soprano repertoire, rising only to a B flat, with nary a top C in sight. Dramatically, the role resembles several Puccini heroines – her closest sister is Tosca – both characters marinated in theatricality. The impressive list of singers includes many of the most celebrated sopranos of the last 120 years, including, in more recent years, Renata Tebaldi, Montserrat Caballé, Renata Scotto, Mirella Freni, Angela Gheorghiu and Anna Netrebko. (Joan Sutherland sang it memorably in Sydney in 1984.)

Opera Australia has assembled a strong cast with the outstanding Albanian soprano, Ermonelo Jaho, scheduled to sing the title role. But, as happens in opera, she came down with a throat complaint just before the première. In the best theatrical tradition, the performance was saved by Natalie Aroyan at the last moment. Aroyan has become well known to Australian audiences in recent years, singing a wide range of major lyric soprano roles, and Adriana is a logical next step vocally for her. The beauty of her voice was immediately apparent in the most celebrated aria of the opera: ‘Io son l’umile ancella’ (‘I am the humble servant of the creative spirit’) early in Act One; her essentially soft-grained voice ideally suited the many lyrical moments of the role. Occasionally she sounded under pressure in the low-lying declamatory aspects of the role, but the soaring upper register revealed the silvery bloom of the voice at its best. She is blessed with a striking physical presence on stage, a performer to whom the eye is drawn; ideally suited to the prominent theatrical aspects of the role. Her death scene was most moving after she kisses the poisoned violets she believes have been sent to her by her lover, Maurizio.

Aroyan was matched by Romanian Carmen Topciu as her rival, the Princess di Bouillon, with her dark, richly-hued mezzo and striking stage presence. The great scene in Act Two between these two was a highlight of the performance, a masterclass in vocal refinement as well as passionate dramatic engagement. The Act Three confrontation between the Princess and Adriana was another scintillating scene where the Princess challenges Adriana to recite something from ‘Ariadne Abandoned’, but is overruled by her husband who wants an excerpt from ‘Phèdre’. Adriana recites the final lines: their implication serves as her revenge on the Princess.

Michael Fabiano as Maurizio and Carmen Topciu as The Principessa (photograph by Keith Saunders)

Michael Fabiano as Maurizio and Carmen Topciu as The Principessa (photograph by Keith Saunders)

American tenor Michael Fabiano – fresh from a successful recital in Melbourne – is one of the most sought-after performers in the lyrico spinto tenor repertoire. He has a voice with a darkish quality to the sound, but with a ringing, rock-solid upper register, all very apparent in his various arias. The voice is large but never sounds forced, while his soft singing reveals an expressive musical intelligence and great vocal control. He cuts a dashing stage figure as Maurizio and is ideally suited to a role that has been sung by many of the greatest tenors since Caruso. Fabiano produced some of the finest singing heard in Sydney for a long time and fully deserved the ovation that greeted several of his arias as well as his curtain call. He is a fine singer at the peak of his powers.

The fourth principal is stage manager Michonet, the most sympathetic and warm-hearted character in the opera. Young Italian baritone Giorgio Caoduro is carving out an impressive career, particularly in Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi roles, but he was not completely convincing here as the older, world-weary character, in love with Adriana but doomed never to fulfil his desires. Though he captured much of the kaleidoscopic emotional journey of the character, seeking always to protect her, Caoduro lacked some of the vocal warmth and gravitas essential to the role.

In the smaller but key roles of the Prince di Bouillon and the Abbé, Opera Australia stalwart Richard Anderson was in fine sonorous voice, and Virgilio Marino provided strong vocal and dramatic performances. Their intrigues provide the impetus for much of the action of the opera, and both provided vivid characterisations. Anthony Mackey, Adam Player, Jane Ede and Angela Hogan were all convincing in their comprimario roles, providing comedic variety and energy as Adriana’s theatrical colleagues.

This is an opera that provides a wide range of scenic and dramatic possibilities for the largely Italian creative design and production team in this co-production between Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Fundación Ópera de Oviedo, and Opera Australia. The production, directed by Rosetta Cucchi, oscillates between the original, eighteenth-century period, for the first two acts; Paris in 1930 for Act Three; and an undefined present for the final act. Cucchi directs her performers with a sure sense of style and strong engagement in the emotional underpinning of the drama, with excellent use of the playing spaces. The striking costumes by Claudia Pernigotti provide a visual feast and contribute much to the drama.

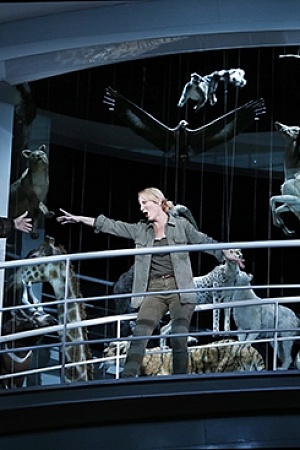

Emalyn Knight, Louis Fontaine, Brendan Irving, Ashley Goh, Jessica Smithson, and the Opera Australia Chorus (photograph by Guy Davies)

Emalyn Knight, Louis Fontaine, Brendan Irving, Ashley Goh, Jessica Smithson, and the Opera Australia Chorus (photograph by Guy Davies)

Set designer Tiziano Santi brilliantly creates two starkly contrasting eighteenth-century Parisian scenes in the first half: an appropriately chaotic theatre backstage for Act One, and a claustrophobic, two-roomed set for Act Two. Act Three is a stylish, dark-hued 1930s nightclub setting, whereas the final scene is a bare film studio where the final drama plays out. Santi is ably abetted by lighting designer Daniele Naldi, and video designer Roberto Recchia, whose black-and-white films contribute much to the atmosphere and drama of the final two acts. Choreographer Luisa Baldinetti created the vivid, short ballet for Act Three in which gravity-defying aerialist Brendan Irving was sensational.

Musically presiding over the performance of this richly varied work was conductor Leonardo Sini. The orchestra and chorus were in excellent form, with some impressive instrumental solos. Sini maintained the momentum of the drama, but allowed the players full reign to luxuriate in this lush score.

All credit to Opera Australia for staging the opera in this fine production: a fascinating contrast with the usual late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Italian repertoire, where Puccini always looms large. Despite its convoluted plot, Adriana is a deeply satisfying work, one that provides great opportunities for expressive performers and the wider creative team.

Adriana Lecouvreur (Opera Australia) continues at the Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House until 7 March 2023. Performance attended: 20 February.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.