Twelfth Night

Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night is a perennial favourite on the Shakespeare calendar (pun intended). The twelfth night of Christmas celebrations was the olden-day version of New Year’s Eve, not because it was the last day of the year but because it was the last day of festivities, with everything returning to normal after the hangover. As such, it was celebrated as a topsy-turvy night where homeowners would play servant to their servants and bring them gifts, with much frivolity and goodwill – a bit like the boss getting pissed at the staff party.

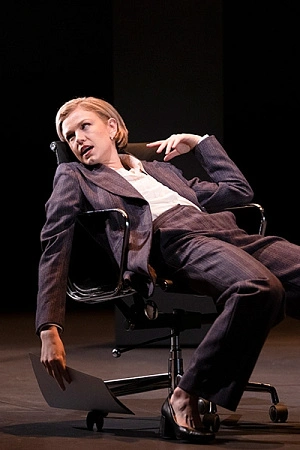

Although Shakespeare’s comedy, set in mythic Illyria, is never really about this calendrical event, it certainly takes on the topsy-turvy energies of twelfth night revelries – its plot following the cross-dressing heroine (Viola), who comes from a good family but is shipwrecked, so decides to play the ‘male’ go-between page (Cesario) for Duke Orsino, who sends ‘him’ to woo the Countess Olivia, who instead falls for ‘him’ as Cesario, but Viola rebuffs Olivia because ‘he’ is a she who’s now fallen for Orsino, who continues treating ‘him’ as the boy he thinks her to be until her twin brother Sebastian arrives to create further confusion, until the play culminates in appropriately ‘heterosexual’ pairings at the end. All rather risqué stuff for Shakespeare’s England!

Continue reading for only $10 per month.

Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review.

Already a subscriber? Sign in.

If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.