Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao

.jpg)

I think that as a person Gauguin did a lot of dodgy things but as a painter he did a wonderful job. All the interesting work happened when he came to Polynesia, inspired by the Other.

Yuki Kihara, 2019

These words put the case for and against Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) in a nutshell. Kihara speaks with the authority of a Pasifika, a transgender Japanese-Samoan artist who wittily restaged two dozen Gauguin paintings as colour photographs in her Paradise Camp series. Kihara dressed and posed Fa’afafine – men living and dressing in the manner of women – and her work cements the iconic status of Gauguin’s ‘wonderful’ imagery.

What were the ‘dodgy things’ Gauguin did? The list is long, from plagiarising texts in his own writings and appropriating Māori iconography, to more egregious acts like abandoning his Danish wife and five children, and living ‘in sin’ with teenage girls in far-distant Tahiti and the Marquesas.

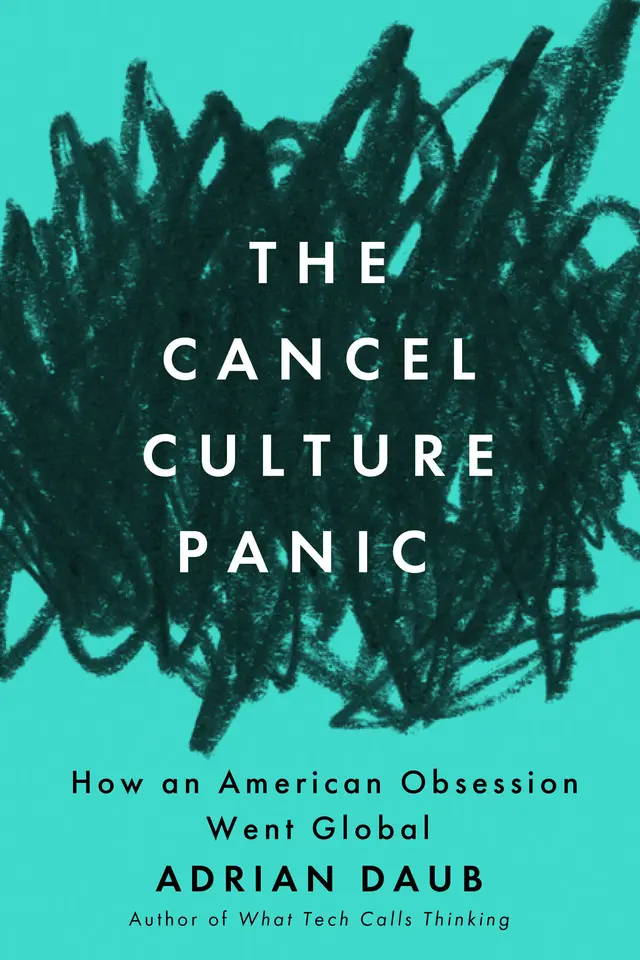

The National Gallery has taken a risk in devoting a major retrospective to this bad man who produced great art. Sasha Grishin attempted a ‘pile-on’ in his reactive piece for The Conversation, drawing on Gauguin’s letters to reveal the ugly misogynistic claims of a colonial settler 130 years ago. But the National Gallery, in its beautifully produced exhibition catalogue, addresses these issues directly. The feminist scholar Norma Broude, in her essay ‘Paul Gauguin in the Era of Cancel Culture’, introduces Australian readers to the postcolonial critique that, since Abigail Solomon-Godeau (1989), has revealed a problematic, middle-aged Gauguin as predatory cultural colonist. Yet Broude finds today’s ‘cancel-culture’ version of events too simplistic. Like fellow essayist Nicholas Thomas (whose new book Gauguin and Polynesia is a must-read), she argues that Gauguin’s cohabitation with girls we would call minors needs to be seen in its historical setting. In that time and place, such relationships could be approved by Tahitian parents as beneficial, while Tahitian standards about sexuality differed markedly from today’s.

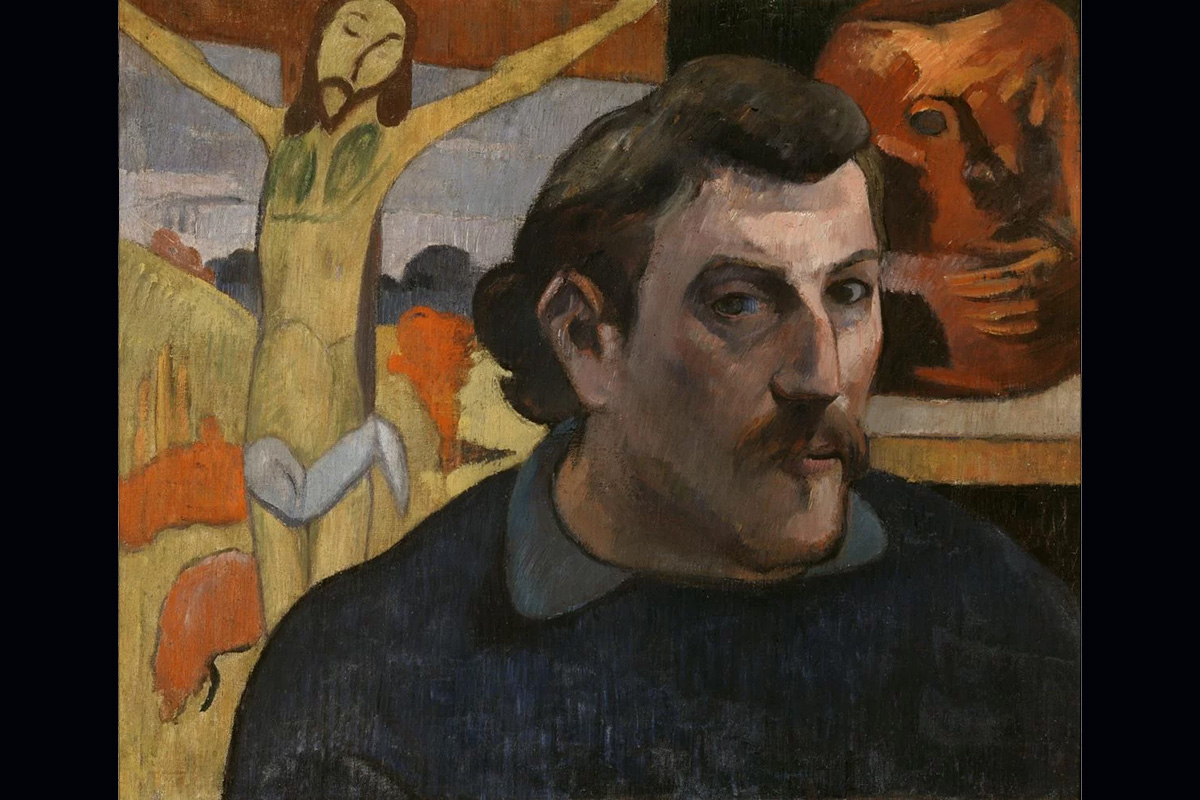

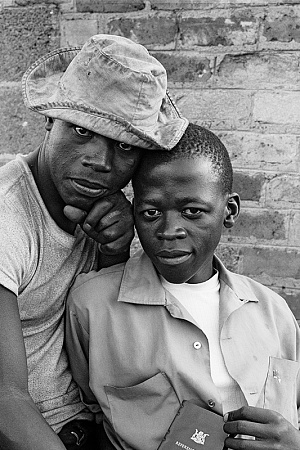

Paul Gauguin, Portrait of the artist with ‘The yellow Christ’ (Portrait de l’artiste au ‘Christ jaune’), 1890–91, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, purchased with the participation of Philippe Meyer and Japanese sponsorship coordinated by the daily Nikkei 1993 (photograph by GrandPalaisRmn (musée d'Orsay) / René-Gabriel Ojeda and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia)

Paul Gauguin, Portrait of the artist with ‘The yellow Christ’ (Portrait de l’artiste au ‘Christ jaune’), 1890–91, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, purchased with the participation of Philippe Meyer and Japanese sponsorship coordinated by the daily Nikkei 1993 (photograph by GrandPalaisRmn (musée d'Orsay) / René-Gabriel Ojeda and courtesy of National Gallery of Australia)

In the new Gauguin scholarship of Broude, Thomas, or Elizabeth Childs (all building on the legacy of Bengt Danielsson), we see the seriousness of Gauguin’s engagement with French Polynesia, where he spent ten years living and painting. Broude looks in detail at Gauguin’s grandmother, the pioneering feminist Flora Tristan, to reveal in Gauguin’s art and thought a validation of Polynesian matriarchy and sexual equality, as against the colonial Catholic mores which Gauguin opposed in word and deed. I would link these ideas to Stephen Eisenman’s controversial book Gauguin’s Skirt (1997), which investigated Polynesian sexuality and the ‘third sex’ of Fa’afafine or mahu, highlighting the artist’s own sexual ambiguity and the possibility that some adult figures in his paintings were posed by Fa’afafine.

What do Polynesian intellectuals today make of these largely Anglophone debates about sexual mores? The NGA helps answer the question, establishing a program to frame Gauguin in an indigenising, postcolonial context. New Polynesian art dominates a large open gallery before entry to the exhibition wing. Two vast walls and a floor are covered with a kaleidoscope of colour and imagery. Block-printed wall hangings by Cook Island man Numa Mackenzie are festooned with traditional weapons, photographs old and new, and anticolonial slogans (‘Landback!’). Vitrines contain Pasifika kitsch objects à la Destiny Deacon. This joyous but politically pointed profusion is the work of the ‘SaVĀ’ge K’lub’, a collective of contemporary artists led since 2010 by Rozanna Raymond, with a base in Auckland, but membership stretching across Te moana nui (Pacific Ocean) to Tahiti and beyond.

The dance and song troupe O Tahiti E from French-speaking Tahiti chose to make tableaux vivants that in one case mimicked a key Gauguin picture used in NGA publicity. At the opening conference, two Tahitian women, brilliant academic essayists, were keen to discuss broader resonances. Vaiana Giraud was one: a Tahitienne who has done a doctorate on Gauguin’s writings. Mariama Bono, director of the prime cultural facility the Musée de Tahiti et des IÎes, affirmed that, beyond his value to tourism, Gauguin is of little interest to most Tahitians. She emphasised that not a single original painting by the artist exists in her country. Surely the time is right for the Musée d’Orsay to donate a couple of Gauguins to this new French Polynesian museum?

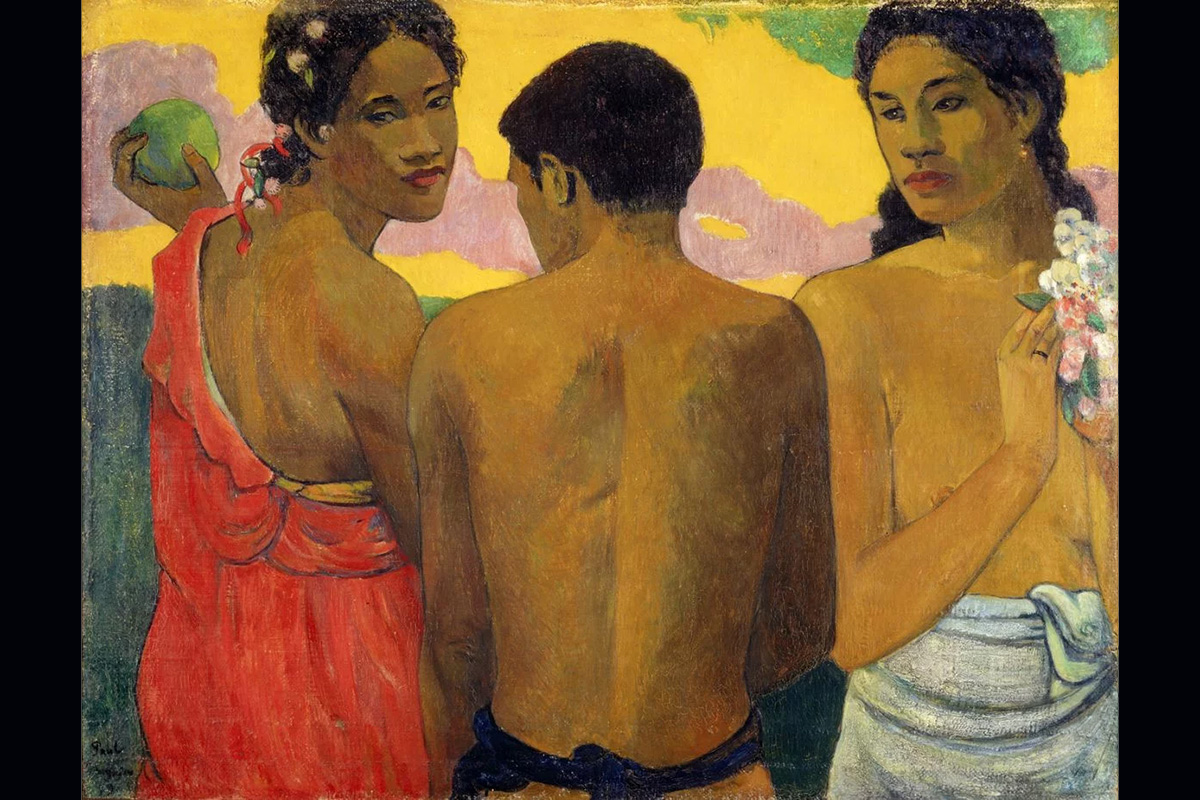

Paul Gauguin, Three Tahitians (Trois tahitiens) 1899 oil on canvas 73 × 94 cm National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Presented by Sir Alexander Maitland in memory of his wife Rosalind 1960, NG 222 (courtesy of National Gallery of Australia)

Paul Gauguin, Three Tahitians (Trois tahitiens) 1899 oil on canvas 73 × 94 cm National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Presented by Sir Alexander Maitland in memory of his wife Rosalind 1960, NG 222 (courtesy of National Gallery of Australia)

The exhibition itself is a fine and balanced presentation of Gauguin’s fascinating work. French curator Henri Loyrette handles the material with subtlety and flair. His long essay is beautifully written and begins with the naval surgeon Victor Segalen, who arrived in Tahiti just after the painter’s death, triggering thoughts on Gauguin’s engagement with colonial life, with Polynesian people, and with posterity. Yet Loyrette argues that Gauguin never separated himself from the Parisian scene. He lived in both worlds simultaneously, via the gallery of European art reproductions in his tropical studio, his letters home, and the constant need for remuneration. Despite chronic health problems and various addictions, Gauguin was an ambitious player who achieved recognition in France from progressives, including Edgar Degas (who amassed a big Gauguin collection), the critic Octave Mirbeau, the Symbolist poet Mallarmé, and the biographer Charles Morice. In this essay and the wall panels, Loyrette (in classic French manner) and the NGA curatorium steer clear of contentious biographical issues, as my colleague Tai Mitsuji has pointed out in his Guardian review.

The need to decolonise or indigenise this exhibition is also evident in the inclusion of Tahitian artefacts. This is familiar practice at the NGA, which has previously integrated contemporaneous First Nations artefacts into hangs of nineteenth-century Australian painting. The difference is that Gauguin, virtually for the first time in European art history, opened himself to the aesthetic inspiration of such objects. Gauguin’s World is replete with his timber carvings (influenced by his visit to the Māori wing of the Auckland Museum in 1895), modelled-clay figurines, and his biomorphic sculpture. These fired clay objects, some of them glazed, are strange amalgams of floral and animal shapes that began during Gauguin’s Brittany phase, and are indebted to the ancient Peruvian sculpture he first saw as a child growing up in Lima.

Another strength is the inclusion of Gauguin’s two suites of prints, the Café Volpini lithographic drawings on yellow paper (exhibited at the Exposition Universelle of 1889), and the powerful imagery of Gauguin’s woodcuts in hybrid indigenising style for his unpublished book Noa-Noa. The various carvings in timber – from patterned walking sticks and serving spoons to figural panels and statuettes – are in Gauguin’s trademark eclectic manner, inspired by an imaginarium that ran from Māori symbolism to the Buddhist friezes of Borobudur. It is no exaggeration to say that such sculpture, among the 227 works in his posthumous retrospective at the 1906 Salon d’Automne in Paris, inspired a second generation (after his Pont-Aven followers) to Gauguinisme, beginning with Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

The room of early works by the Impressionist Gauguin is a revelation. A Sunday painter and stockbroker who was laid off in the crash of 1884, Gauguin learned with alacrity at Camille Pissarro’s elbow. His sense of composition was always irreproachable, be it in the successive painting modes of Pissarro, Degas, Émile Bernard, and, above all, Paul Cézanne. Cézanne, whom Loyrette hardly mentions, said of the voyager Gauguin that ‘he’s pinched my “petite sensation” [Cézanne’s word for his unique way with the brush] and paraded it around all the steamboats’. Gauguin was an aesthetic bowerbird, but one who broke through each borrowed convention to excel finally in an art wholly his own. He composed with flat planes of brightly contrasting colour which summarised human form – whether naked or clothed – with a resounding gravity. His paintings of the figure are both refined and raw; intimate and unfiltered.

Across the seven rooms of this large exhibition, the logic of Loyrette the art historian is attuned to image-citations. He made efforts to borrow works never hung together before, like the two versions of boys wrestling on the grass at a Brittany weir, or the pair of still lifes with a Delacroix drawing on the wall behind. You can track motifs across woodcarving and prints to paintings – the gallery sightlines promote it. Loyrette also emphasises Gauguin’s borrowings from the precious art reproductions on the walls of his Polynesian studios: Gauguin’s sensibility lodged simultaneously in France and in Oceania.

Restless experiment is apparent across all media; all that’s missing are a few more major paintings. The murderous Russian invasion of Ukraine put paid to Loyrette’s plan to borrow from the extensive Shchukin and Morosov collection of Gauguins in Moscow (which I was fortunate to study in September 2019). The Orsay has loaned a core of pictures, but up to eight of them have visited these shores before, travelling to Sydney in 1994 or Canberra in 2009. The diligence and ambition of the curator (former director of both the Musée d’Orsay and the Louvre) – coupled with travels by NGA Director Nick Mitzevich, Carol Henry from partner Art Exhibitions Australia, and Houston MFA’s Gary Tinterow – have resulted in a record sixty-five institutions and private collectors lending to Canberra.

This is the work – the travel to institutions, the pleading, and the face-to-face suasion (at which the golden-tongued Loyrette evidently excels) – that alone can guarantee a monographic show of intellectual coherence. The easier and less expensive curatorial option is the blockbuster sourced from one main collection, such as the recent Matisse or Kandinsky exhibitions held in Sydney.

At the end of the day, despite the odium, despite the brickbats, Paul Gauguin continues to command major exhibitions, and justifiably so. This is not just because of his undeniable historical significance or the conceptual irritant of the Gauguin controversies. It is because people continue to find the paintings in particular so beautiful, so surprising. That hero of symbolists the poet Charles Baudelaire wrote ‘le Beau est toujours bizarre’. Gauguin proves him right again and again.

Gauguin’s World: Tōna Iho, Tōna Ao continues at the National Gallery of Australia until 7 October 2024.

Comments (2)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.