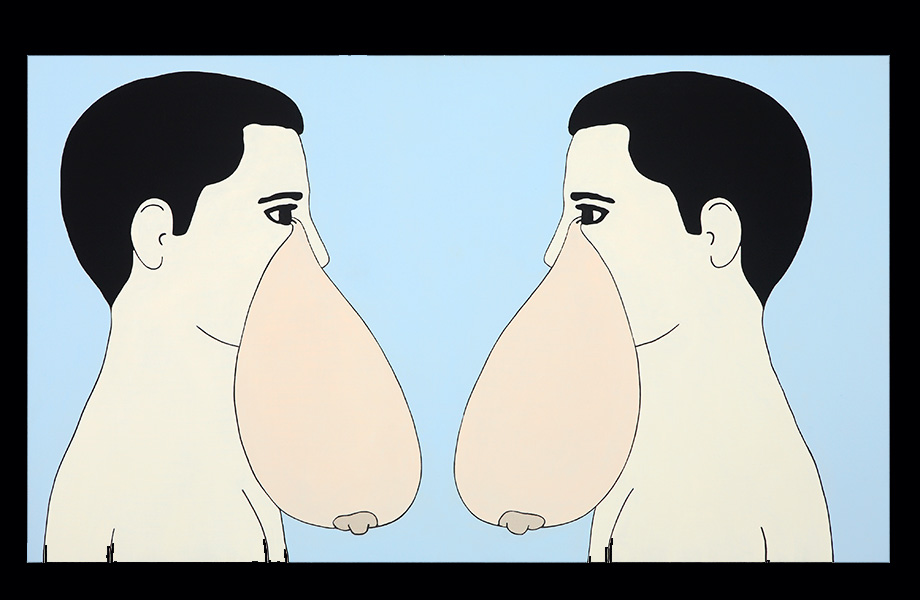

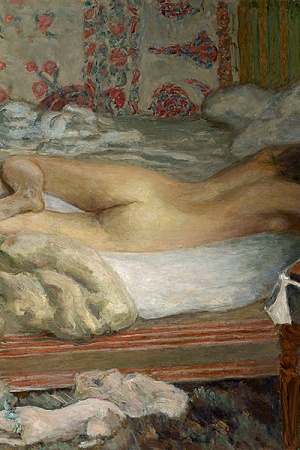

Brent Harris: Surrender & Catch

Art travels, or it does not – in the latter case, often unjustly. Artists known in one country are not always visible beyond it, just as national cultures of literature and music often develop and remain supported entirely from within. This does not mean, however, that the artists, writers, and musicians themselves are untravelled, nor that their individual practices evolve in ignorance of what is happening elsewhere.

Brent Harris might be judged one such artist, a painter and printmaker whose work is known chiefly in Aotearoa New Zealand, where he was born in 1956, and Australia, where he was trained and has lived since graduating from art school. Despite his travels and residencies overseas and appearances in group shows in Europe, Harris has not yet enjoyed the level of international recognition that he so clearly deserves. The Art Gallery of South Australia’s new exhibition ‘Brent Harris: Surrender & Catch’ (mounted in partnership with the TarraWarra Museum of Art, where a first iteration of the exhibition was on display earlier in 2023-24), along with an accompanying volume edited by curator Maria Zagala, offers a compelling retrospective of this singular artist’s work, making what might be considered a case for acclaim, and one that I found convincing.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.