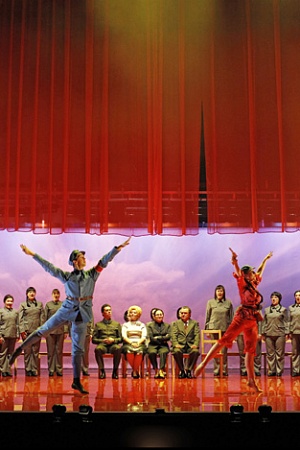

Kaddish: A Holocaust Memorial Concert

This concert was the fourth, and perhaps most immediately relevant, in a series of concerts conceived over the past six years by artist-in-residence Christopher Latham for the Australian War Memorial. As with the Diggers’ Requiem (2018), Vietnam Requiem (2021), and the Prisoners of War Requiem (2022), Latham has created a narrative to accompany a series of musical works intended to make the history it explored ‘more conscious, identified and understood’.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (2)

Honest and unswerving in its depiction across the whole,musical “adventure”.

The reference to current, international

events seems to reflect an appropriate

question, to be asked by future generations. Thank you. Roger H⯑

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.