Truth

Silence is the central theme of Patricia Cornelius’s latest play, a theatrical documentary about the life and times of Julian Assange, focusing especially on his persecution following the publication of classified US military and diplomatic documents in 2010. This theme is announced in huge white letters on a bank of video screens above the stage in the play’s opening moments, where it lingers against the dark background like an accusation.

Silence, however, is various and Cornelius presents it in manifold ways: the silence of the persecuted, the silence of the indifferent, the silence of the complicit, and the silence of bureaucratic secrecy and evasion.

The play begins with scenes from the provincial childhood of an intelligent outsider: Julian Assange as the archetypal nerd discovering the world of computers. Initially, the attractions of silence are sympathetically suggested. The five members of the ensemble, each representing a version of Assange, speak directly to the audience:

– to think differently is like some almighty crime

– to see solutions that others can’t see

– to offer another way of thinking

– is considered some kind of treachery

– silence is best

This sort of jostling rhythm and energy is specific to the work of Patricia Cornelius and is integral to whatever contribution she has made to Australian playwriting. The lines are short but heavy, like impasto slashes, suggesting the perpetual unrest that is her theatrical signature.

The subject matter, at least in these early scenes, is also familiar. Cornelius has long positioned herself as an advocate for the voiceless and the marginalised, the fringe dwellers and those who are too easily ignored. It is an intention that connects such diverse works as Lilly and May (1986), Last Drinks (1992), Do Not Go Gentle (2010), and Shit (2016), not to mention her contribution to the landmark Who’s Afraid of the Working Class? (1998). And it surfaces in her treatment of the young Townsville-born Assange.

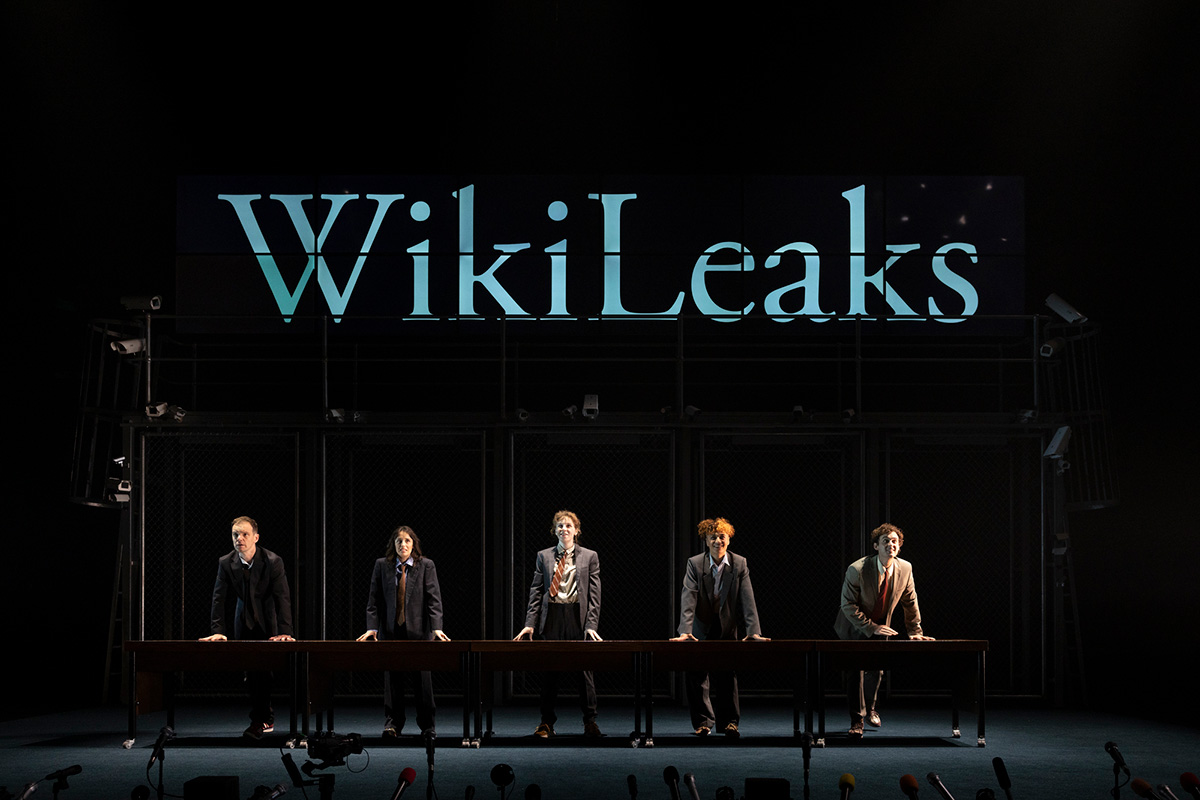

Truth (photograph by Pia Johnson)

Truth (photograph by Pia Johnson)

The play hurtles through an account of the major events in Assange’s life: his arrest in the early 1990s on charges of cybercrime, his creation of Wikileaks, the publication of various censored and restricted documents, the Swedish sexual assault case, his retreat to the Ecuadorian Embassy, and his imprisonment in London’s Belmarsh High Security Unit. Director Susie Dee uses many cameras throughout the performance to create visual interest in what is otherwise a minimalist presentation, with only a few desks and a background of wire-mesh cages below a raised catwalk and bank of monitors.

Cornelius has reflected on current events in some of her previous work – the story of Savages (2013), for example, was influenced by the cruise ship death of Dianne Brimble – but Truth is far more expository. This is not epic theatre so much as newspaper theatre, in which the audience is given telegraphic descriptions of recent events with a lot of verbatim quotes.

This approach will prove challenging or frustrating for those already familiar with the intricacies of the Assange saga. On the other hand, Truth is a play that operates under the assumption that the sustained campaign of vilification directed against Assange was largely successful. No doubt there are many who still believe that he was fugitive from justice or that his release of unredacted documents put the lives of local informants at risk. This production aims to fill the gap, presenting a story that, while possibly known in parts, may not be known by all theatregoers in its entire troubling context.

In the middle of the performance, there is a screening of the Collateral Murder video, with the actors sitting at desks, facing the screen, doing the voices of the military personnel in real time. This is the video that recorded, among other atrocious things, the shooting of an unarmed injured man and his unarmed rescuers by the crew of an American military helicopter in Iraq. This was not a tragic mistake but a deliberate war crime, though none of the soldiers or their commanders was ever prosecuted. It is a sombre moment in the play because the video retains its power to dismay, even in this theatricalised context.

It was after the publication of Collateral Murder that the attempt to silence Julian Assange began in earnest. Nils Melzer, the former United Nations special rapporteur on torture, wrote in an official letter in 2019 that in all his years of work with victims of war and political oppression, he had ‘never seen a group of democratic States ganging up to deliberately isolate, demonise and abuse a single individual for such a long time and with so little regard for human dignity and the rule of law’. The point, of course, was not simply to crush Assange but to distract the world from the crimes exposed by Wikileaks.

The instrumentalisation of sexual assault allegations by two women in Sweden was crucial to this effort. This episode is handled here by Dee and Cornelius with more spark and wit than any other part of the Assange story. The two women, played by Emily Havea and Eva Seymour, tell the audience their side of the story, emphasising the capture of the case by Swedish prosecutors who repeatedly ignored their wishes. All this is done with extensive quotations from Melzer’s investigation, detailed in chapter six of his book The Trial of Julian Assange: A story of persecution (2022).

There are also less effective cameos by Chelsea Manning, played by Eva Rees, and Edward Snowden, played by Tomáš Kantor.

The most affecting scenes in Truth are the two interludes that pull us momentarily from the hurly-burly of recent history. The first is a vignette about the oppressive silence that settles over the dinner table of a family torn apart by sexual abuse. The other is about a woman (Emily Havea) who is being electronically stalked by a man. Written at a different time, under different conditions, it is possible that Truth might have contained more of these vignettes and less of Assange and his speechifying. The play might have been less linear and less freighted with extracts and harangues.

In his introduction to the published version of Cornelius’s Do Not Go Gentle, Julian Meyrick writes: ‘At the heart of all plays with something to say lies something that cannot be said. It is this ineffability, this silent soul, which gives drama its flavour, shape and force.’ This sort of silence, this deep quiet that is not at all equivalent to the politics of silence, cannot always be felt in Truth. It can be experienced, fleetingly, in some of the contrasts between scenes, particularly the domestic sketches described above. What is the connection between these scenes and the larger story of Assange and the whistleblowers he supported? It is not easy to articulate in words, but it can perhaps be intuited.

Cornelius, however, doesn’t create room for this kind of reflection. There is a sort of desperation in her attempt to jam the whole Assange story into seventy minutes. And yet this urgency is belated, because Assange was released last year and has returned to Australia. I think the play’s manic verbosity must therefore be understood as a deliberate counter to the prolonged silence that once dominated the discourse around Assange’s plight, which must now be obliterated as part of our collective reckoning.

Truth continues at the Malthouse Theatre until 8 March 2025. Performance attended: February 18.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.