Mahler Resurrection Symphony

One consequence of the popular success of Bradley Cooper’s biopic Maestro (2023) may well be that it helps to reinforce the cultural significance of Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony (Resurrection) for another generation. In the film we witness a faithful recreation of the final moments of Leonard Bernstein’s legendary performance of the Resurrection in Ely Cathedral in 1973. Apart from being an excuse to depict a glorious musical moment, the scene acts as the fulcrum around which our own character assessment of Cooper’s Bernstein pivots. Immediately after the conclusion, his long-suffering wife proclaims that ‘there’s no hate in [his] heart’. Mahler’s music here foretells not so much a physical resurrection as the conductor’s redemption.

Fast forward to our own lives, and perhaps we bring a similar expectation to the work. For a brief, fragile moment, might such music not ‘redeem the murderous, imbecile mess which we dignify with the name of history’, as George Steiner once wrote about Beethoven’s music? We could certainly be forgiven for wanting such an enchantment today, when so many of the social and political certainties of the past seventy years appear to be crumbling before our eyes.

If I seem to be making overly portentous claims about a piece of late nineteenth-century symphonic music, we need only remember that Mahler himself held similar ambitions for his Second Symphony. In his own (later suppressed) program note for a performance of the work in Dresden in 1901 (it was ultimately premièred in Berlin in 1895), he suggested that it dared to ask ‘What is life – and what is death? Why did you live? Why did you suffer? Is it all nothing but a huge, frightful joke?’ Mahler also observed that all of us ‘must answer these questions in some way, if we want to go on living.’

Under the weight of such interpretative demands, Mahler composed music which appropriately strains at its formal and expressive seams from the outset. The tremolo that opens the first movement references both the opening of Beethoven’s own monumental essay in redemptive hope, his Ninth Symphony, and the violent storm that opens Wagner’s Die Walküre (further references to both works will follow). The first theme we hear in the oboes and English horn also hints at the Gregorian chant ‘Crux fidelis’ (‘Faithful cross’) and at material from the finale of Mahler’s own First Symphony. All of it is then packaged up as a funeral march. We are made unmistakably aware that this is music conceived on a vast and ambitious scale.

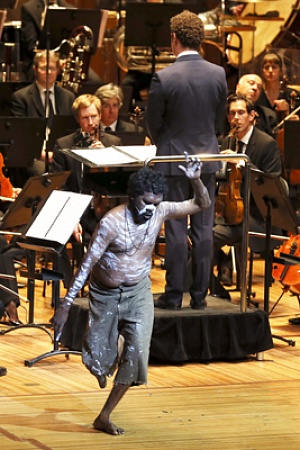

Performing the work to open its 2025 season, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra met the array of interpretative challenges that it presents across its five movements with largely unwavering confidence and élan. Mahler’s penchant for complex textures of interweaving tutti and solo lines across the orchestra demands clear direction and strong individual performances from all sections of the orchestra, as well as from choir and soloists. The full ensemble under Chief Conductor Jaime Martín delivered.

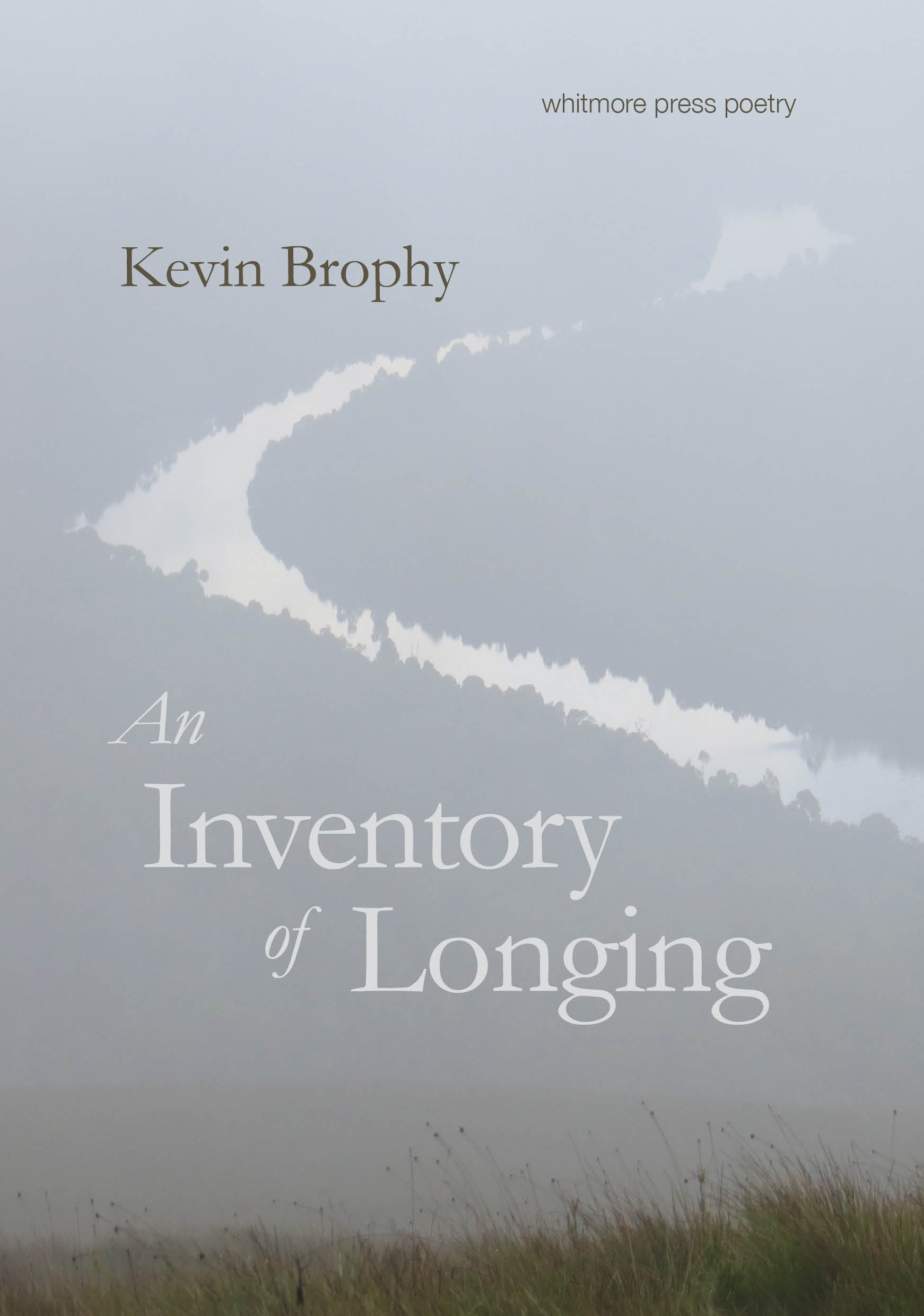

Mahler Resurrection Symphony (photograph by Laura Manariti)

Mahler Resurrection Symphony (photograph by Laura Manariti)

Particularly impressive were the instrumentalists, who led from both ends of the pitch spectrum: the double bass section, and Principal Piccolo Andrew Macleod. To be sure, there were stand-out performances across all sections, and they were in turn well matched by the vocal soloists and choir, who appear in the symphony’s final two movements.

Berlin-based Scottish mezzo-soprano Catriona Morison performed Mahler’s fourth movement setting of ‘Urlicht’ from Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Youth’s Magic Horn) with beguiling sincerity and obvious depth of feeling, using her considerable dynamic range and rich timbre to full effect. Australian soprano Eleanor Lyons (current residing in Vienna) was her equal in their brief vocal exchanges in the fifth movement finale, her clear, powerful, voice comfortably able to punch through the amassing orchestral and choral forces as required.

The MSO Chorus under chorus director Warren Trevelyan-Jones delivered their crucial concluding role in the symphony to their habitual high standard, and did so also from memory, which helped to make their entry seem to emerge out of the texture like Pallas Athene did from Zeus’s forehead; something both inevitable and fully formed. Mahler’s vision of resurrection, when it eventually came, was thus splendidly realised. Here is an ecstatic vision of a deity who, in the end, does not seek to judge us but rather blesses all creation with, and through, unconditional love.

A music critic, alas, does not have quite the same luxury. I am obliged to point out that no electronic keyboard will ever properly address the ongoing need for Hamer Hall to rectify its lack of a pipe organ (in this case, perhaps thankfully, I struggled to hear the synthesised version at all). I also wondered whether the MSO really needed to fly in two vocal soloists (excellent though they were) from Northern Europe, apparently just for this performance. Were there really no Australian-based vocalists up to the task? Morison is at least giving a vocal recital while she is here (March 16 in the Utzon Music Room, Sydney Opera House, with pianist Auro Go). Based on what we heard in Hamer Hall, that would indeed be well worth attending.

Finally, I also note that this performance happened in a week when the promise of any kind of universal vision for humanity seemed under greater threat than at any time since World War II and when Samuel Cairnduff and Greg Barns SC, in an article for John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations, named the MSO as one of several organisations (along with the National Gallery of Australia, the Sydney Theatre Company, and Creative Australia) now exhibiting signs of ‘cultural McCarthyism’. This is because, Cairnduff and Barns argued, of these organisations’ punitive polices towards artists who have drawn attention to, or expressed empathy for, victims of the war in Gaza, in and through their creative work.

As I left Hamer Hall, it occurred to me that Mahler’s music surely asks us to think, feel, and ultimately do better than that.

Maler’s Resurrection Symphony was performed in Hamer Hall, Art Centre Melbourne on 27 March 2025 and will be repeated there on March 1.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.