Whither (or whether) Opera Australia?

These are challenging times for Australia’s national opera company, and not just because many critics and operamanes question whether Opera Australia is in fact remotely ‘national’ in terms of programming.

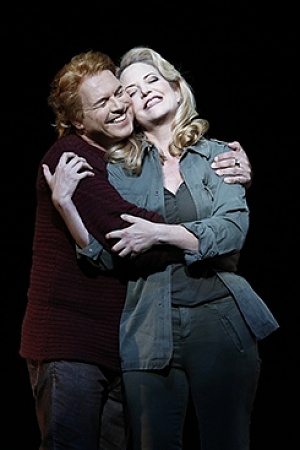

Since 2020 the company has recorded consecutive operating losses. Recently, it lost its artistic director (Jo Davies) and its CEO (Fiona Allan). Reviews of some of its 2024 productions were lukewarm at best. The ill-fated production of Sunset Boulevard – presumably a loss-making venture – has reignited concerns about OA’s commercial reliance on musicals and led many to ask whether an ‘opera’ company handsomely funded by Creative Australia should be dependent on such repertoire.

OA’s appearances in Melbourne are few and tokenistic, reviving old resentments about the loss of the much-lamented Victoria State Opera in 1996. Smaller companies around Australia – some of them unfunded by government – are providing innovative programming, to critical acclaim.

Currently, Creative Australia is undertaking a review of OA’s management and operations. The review will be led by Gabrielle Trainor, a lawyer and former journalist. Creative Australia has told ABR Arts: ‘As we do with many organisations, Creative Australia is working alongside Opera Australia to strengthen its sustainability. To this end, we are commissioning a review of its governance frameworks, which will identify any potential areas for improvement based on leading practice. The report will not be publicly available.’

ABR Arts wonders why a taxpayer-funded review of such importance for the art form will not be made available to opera lovers and arts professionals. Why should it be a purely internal process, without public feedback? Transparency, surely, is a good thing.

In this special feature, ABR Arts has invited leading arts critics, editors and professionals to comment on OA’s present exigencies and how the company should operate in the future. It seems timely to reflect on what kind of national company we need and can sustain, with reference to scale, funding, repertoire, artistic vision, leadership, and national scope.

Peter Rose, ABR Arts

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.

Comments (3)

What indeed IS wrong? After reading this article I have to conclude it must be Management/ Board.

I am NOT wealthy but fly down from Brisbane as often as I can. But I will not come for a Musical. So many younger people just don't have the money.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.